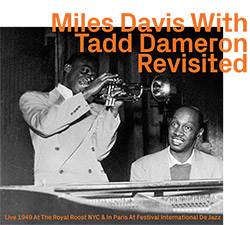

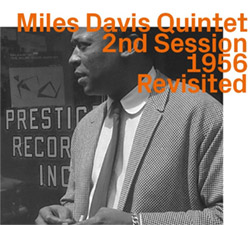

Recorded in the same October 1956 Rudy Van Gelder sessions that are heard on Miles Davis' Cookin' and Steamin' albums, these alternate takes with his quintet of John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on double bass and Philly Joe Jones on drums give us a unique view on the consistency and strength of the famous and foundational hard bop band.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 2.00 units

Sample The Album:

Miles Davis-trumpet

John Coltrane-tenor saxophone

Red Garland-piano

Paul Chambers-double bass

Philly Joe Jones-drums

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156114024

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1140

Squidco Product Code: 32590

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2022

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Recorded at Rudy Van Gelder Studio, in Hackensack, New Jersey, on October 26th, 1956.

"It's almost impossible now to screen an ambitious wildlife documentary series without running a little "how it was done" segment at the end. We are invited to marvel at the patience and skill of cameramen who lie in cold/hot/dangerous/wet/sandy conditions for days on end to catch a precious ten seconds of mating or predation. And sometimes we feel that the magic of the original images has been dented a little. We might even feel a little betrayed if some photographic trickery or set-up has been involved.

We are, as a culture, process-obsessed. We need to know how every blockbuster stunt was set up, how CGI effects were created, how a Method actor gained two stone and ate spaghetti three times a day to play a gangster don. In a sense, music has always been the leading edge of this obsession. Young men spent hours lifting and replacing the needle, trying to work out how a particular sound was made. I personally recall the almost obsessive interest I showed after learning that a soft, slightly buzzed note on Miles Davis's Ascenseur pour l'échafaud, a record which is all about process, was caused by a fragment of lip-skin in the mouthpiece.

And then the CD came along and hungrily needed to be filled, and we were treated to "alternate" takes that the artist never expected or wanted us to hear, breakdown, false starts, studio chat ... whole "box sets" of the stuff. Few artists seemed to invite such an approach more than Miles. For a start, everyone does an impression of that infamous husky whisper, and everyone knew, when he went to Columbia that his new way of working was to get his men to play, put on the studio light and tape sometimes industrial lengths of abstract jam, leaving it to Teo Macero to assemble into releasable tracks. The coming of the box set meant we could now hear the jams in their original form.

We'd always known that this was a process he'd learned while in France and invited to make music for Louis Malle's underrated thriller; it's become a cliché that the only good thing about Ascenseur pour l'échafaud is Miles's improvised score. And we'd been aware that while still working for Bob Weinstock's Prestige label, but anxious to move on to the more prestigious Columbia, Miles had attempted to fulfil contractual obligations by recording several albums' worth of material in single marathon sessions. We were expected to understand that this was a slightly cynical move, more about paperwork than music. Records with titles like Cookin', Relaxin', Steamin', Workin', had come off a production line, admirable in its focus and application but constrained by an extra-musical narrative about business arrangements.

Consequently, the recordings made at Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Hackensack, New Jersey, on October 26 1956 have become the plaything of the discographers, whose pleasure it is to tell us that "If I Were A Bell", item #995, was issued as a jukebox 45 before finding its way onto Relaxin', thence to a Greatest Hits package, and the museology of The Legendary Prestige Quintet Sessions. "Sessions", plural, because Miles and his men had recorded a similar marathon on May 11, on which occasion, knowing that he was to turn thirty in two weeks' time and having wasted a least some of his most productive years chasin' sensation in the form of drugs and women, he perhaps needed to get a move on.

Process-obsessed as we are, there is a danger that the music disappears behind an interference wave of anecdote and detail. Here is an opportunity to reflect that, far from being a mere contractual convenience, Miles's marathon recording sessions of May and October 1956 were among his first attempts, a year earlier than the Louis Malle soundtrack date, to allow his music to emerge and evolve in real time by making the recording studio a performance space rather than an artisanal workshop. In later years, associates such as Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock severally - though they must have talked about it - likened Miles to a Zen master whose control over the music was through intuition and flow rather than a strict observance of chords. Those who have tried to elevate Ascenseur pour l'échafaud into an epiphany about the potential of free and abstract playing sometimes fail to recognise that the 1956 sessions, and those of October 26 most particularly, already have something of that quality. Tonally and expressively, they blend into one another when heard in sequence. Though Miles later relied on producers and labels to package his work in marketable bathes, here, it might be argued, the astonishing consistency of vision achieved in these concentrated bursts of music-making, which must have become trance-like as the clock ticked on, was violated when tracks were selected and written down in columns under different release titles.

Here is a chance to hear Miles Davis in something close to real time. Small matter that most collectors of hard bop will have these sides already and will be familiar with a particular running order. Perhaps those who have invested in the complete sessions will have a clearer sense of the continuity of these remarkable sessions, but that now familiar obsession with the burrs and swarf of the studio process may win out over musical appreciation. What happened at Van Gelder's on October 26 1956 is one of the great performances of modern jazz. Surrender to it."-Brian Morton, July 2022

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Miles Davis "Miles Davis, in full Miles Dewey Davis III, (born May 26, 1926, Alton, Illinois, U.S.-died September 28, 1991, Santa Monica, California), American jazz musician, a great trumpeter who as a bandleader and composer was one of the major influences on the art from the late 1940s. Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, where his father was a prosperous dental surgeon. (In later years he often spoke of his comfortable upbringing, sometimes to rebuke critics who assumed that a background of poverty and suffering was common to all great jazz artists.) He began studying trumpet in his early teens; fortuitously, in light of his later stylistic development, his first teacher advised him to play without vibrato. Davis played with jazz bands in the St. Louis area before moving to New York City in 1944 to study at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School)-although he skipped many classes and instead was schooled through jam sessions with masters such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Davis and Parker recorded together often during the years 1945-48. Davis's early playing was sometimes tentative and not always fully in tune, but his unique, intimate tone and his fertile musical imagination outweighed his technical shortcomings. By the early 1950s Davis had turned his limitations into considerable assets. Rather than emulate the busy, wailing style of such bebop pioneers as Gillespie, Davis explored the trumpet's middle register, experimenting with harmonies and rhythms and varying the phrasing of his improvisations. With the occasional exception of multinote flurries, his melodic style was direct and unornamented, based on quarter notes and rich with inflections. The deliberation, pacing, and lyricism in his improvisations are striking. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Miles Davis • Show Bio for John Coltrane "John Coltrane, in full John William Coltrane, byname Trane, (born September 23, 1926, Hamlet, North Carolina, U.S.-died July 17, 1967, Huntington, New York), American jazz saxophonist, bandleader, and composer, an iconic figure of 20th-century jazz.John Coltrane, 1966. Coltrane's first musical influence was his father, a tailor and part-time musician. John studied clarinet and alto saxophone as a youth and then moved to Philadelphia in 1943 and continued his studies at the Ornstein School of Music and the Granoff Studios. He was drafted into the navy in 1945 and played alto sax with a navy band until 1946; he switched to tenor saxophone in 1947. During the late 1940s and early '50s, he played in nightclubs and on recordings with such musicians as Eddie ("Cleanhead") Vinson, Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges. Coltrane's first recorded solo can be heard on Gillespie's "We Love to Boogie" (1951). Coltrane came to prominence when he joined Miles Davis's quintet in 1955. His abuse of drugs and alcohol during this period led to unreliability, and Davis fired him in early 1957. He embarked on a six-month stint with Thelonious Monk and began to make recordings under his own name; each undertaking demonstrated a newfound level of technical discipline, as well as increased harmonic and rhythmic sophistication. During this period Coltrane developed what came to be known as his "sheets of sound" approach to improvisation, as described by poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka): "The notes that Trane was playing in the solo became more than just one note following another. The notes came so fast, and with so many overtones and undertones, that they had the effect of a piano player striking chords rapidly but somehow articulating separately each note in the chord, and its vibrating subtones." Or, as Coltrane himself said, "I start in the middle of a sentence and move both directions at once." The cascade of notes during his powerful solos showed his infatuation with chord progressions, culminating in the virtuoso performance of "Giant Steps" (1959). Coltrane's tone on the tenor sax was huge and dark, with clear definition and full body, even in the highest and lowest registers. His vigorous, intense style was original, but traces of his idols Johnny Hodges and Lester Young can be discerned in his legato phrasing and portamento (or, in jazz vernacular, "smearing," in which the instrument glides from note to note with no discernible breaks). From Monk he learned the technique of multiphonics, by which a reed player can produce multiple tones simultaneously by using a relaxed embouchure (i.e., position of the lips, tongue, and teeth), varied pressure, and special fingerings. In the late 1950s, Coltrane used multiphonics for simple harmony effects (as on his 1959 recording of "Harmonique"); in the 1960s, he employed the technique more frequently, in passionate, screeching musical passages. Coltrane returned to Davis's group in 1958, contributing to the "modal phase" albums Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), both considered essential examples of 1950s modern jazz. (Davis at this point was experimenting with modes-i.e., scale patterns other than major and minor.) His work on these recordings was always proficient and often brilliant, though relatively subdued and cautious. After ending his association with Davis in 1960, Coltrane formed his own acclaimed quartet, featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. At this time Coltrane began playing soprano saxophone in addition to tenor. Throughout the early 1960s Coltrane focused on mode-based improvisation in which solos were played atop one- or two-note accompanying figures that were repeated for extended periods of time (typified in his recordings of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things"). At the same time, his study of the musics of India and Africa affected his approach to the soprano sax. These influences, combined with a unique interplay with the drums and the steady vamping of the piano and bass, made the Coltrane quartet one of the most noteworthy jazz groups of the 1960s. Coltrane's wife, Alice (also a jazz musician and composer), played the piano in his band during the last years of his life. During the short period between 1965 and his death in 1967, Coltrane's work expanded into a free, collective (simultaneous) improvisation based on prearranged scales. It was the most radical period of his career, and his avant-garde experiments divided critics and audiences. Coltrane's best-known work spanned a period of only 12 years (1955-67), but, because he recorded prolifically, his musical development is well-documented. His somewhat tentative, relatively melodic early style can be heard on the Davis-led albums recorded for the Prestige and Columbia labels during 1955 and '56. Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane (1957) reveals Coltrane's growth in terms of technique and harmonic sense, an evolution further chronicled on Davis's albums Milestones and Kind of Blue. Most of Coltrane's early solo albums are of a high quality, particularly Blue Train (1957), perhaps the best recorded example of his early hard bop style (see bebop). Recordings from the end of the decade, such as Giant Steps (1959) and My Favorite Things (1960), offer dramatic evidence of his developing virtuosity. Nearly all of the many albums Coltrane recorded during the early 1960s rank as classics; A Love Supreme (1964), a deeply personal album reflecting his religious commitment, is regarded as especially fine work. His final forays into avant-garde and free jazz are represented by Ascension and Meditations (both 1965), as well as several albums released posthumously." ^ Hide Bio for John Coltrane • Show Bio for Paul Chambers "Paul Laurence Dunbar Chambers Jr. (April 22, 1935 - January 4, 1969) was an American jazz double bassist. A fixture of rhythm sections during the 1950s and 1960s, his importance in the development of jazz bass can be measured not only by the extent of his work in this short period, but also by his impeccable timekeeping and virtuosic improvisations. He was also known for his bowed solos. Chambers recorded about a dozen albums as a leader or co-leader, and over 100 more as a sideman, especially as the anchor of trumpeter Miles Davis's "first great quintet" (1955-63) and with pianist Wynton Kelly (1963-68). Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on April 22, 1935, to Paul Lawrence Chambers and Margaret Echos. He was brought up in Detroit, Michigan following the death of his mother. He began playing music with several of his schoolmates on the baritone horn. Later he took up the tuba. "I got along pretty well, but it's quite a job to carry it around in those long parades, and I didn't like the instrument that much". " ^ Hide Bio for Paul Chambers

5/1/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

5/1/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

5/1/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. If I Were A Bell 8:12

2. Well You Needed 6:21

3. 'Round Midnight 5:25

4. Half Nelson 4:49

5. You're My Everything 4:52

6. I Could Write A Book 5:11

7. Oleo 5:57

8. Airegin 4:26

9. Tune Up 5:42

10. When Light Are Low 7:29

11. Blues By Five 10:01

12. M Funny Valentine 6:04

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Free Improvisation

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Quintet Recordings

Jazz Reissues

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

New in Improvised Music

Recent Releases and Best Sellers

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.