![Morris, Joe: Perpetual Frontier The Properties of Free Music [BOOK] (Riti Publishing) Morris, Joe: Perpetual Frontier The Properties of Free Music [BOOK] (Riti Publishing)](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/MorrisPerpetualFrontier.jpg)

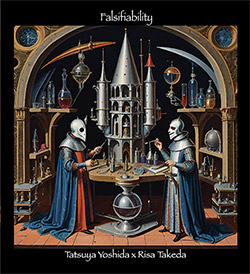

Joe Morris wrote this book to discuss aspects of free music, including responses to his questionnaire written by Joe McPhee, William Parker, Jamie Saft, Ken Vandermark, Marilyn Crispell, Nate Wooley, Jack Wright, Matthew Shipp, &c.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 16.00 units

Sample The Album:

Joe Morris-author

Contributors:

Marilyn Crispell

Charles Downs

Joe McPhee

Alex Ward

Matthew Shipp

Ken Vandermark

Jack Wright

Simon H Fell

Agusti Fernandez

Nate Wooley

William Parker

Mary Halvorson

Nicole Mitchell

Katt Hernandez

Jamie Saft

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 9780985981006

Label: Riti Publishing

Catalog ID: 9780985981006

Squidco Product Code: 16785

Format: BOOK

Condition: New

Released: 2012

Country: USA

Packaging: Book

Guitarist and bassist Joe Morris wrote this book to discuss free music as an art form, with sections on the approach, platform, melodic structure, pulse, interaction and form of free jazz. He provides example methodologies on unit structures, harmolodics, tri-axiom theory, and European Free Improvisation. The second half of the book is a series of responses to a questionnaire that Morris devised and posed to 15 musicians, including Joe McPhee, William Parker, Jamie Saft, Ken Vandermark, Marilyn Crispell, Nate Wooley, Ja24.ck Wright, Matthew Shipp, &c.

"Free music is an art form that has been made by individuals who operate without regard for critical or institutional approval, who invented the way they play their instruments and invented platforms on which to play music, based on whatever aesthetic value they thought mattered to them." -Joe Morris

Perpetual Frontier

an essay by Joe Morris

(published at Point of Departure

My forthcoming book is titled Perpetual Frontier: The Properties of Free Music (riti pub). It is a meta-methodology, or a methodology that can be used to construct a methodology. It does that by describing properties - things that are always used and are always adjusted in every methodology within Free Music. The properties are explained in sections that describe the construction of a methodology that informs process while allowing constant input from all players. The why, what, and how of free music are explained in simple, readable terms that any musician or non-musician can understand. There are sections on approach, melodic structure, pulse, interaction, and form. I include descriptions of four seminal methodologies: Unit Structures, Harmolodics, Tri-Axiom Theory, and European Free Improvisation. The descriptions are accurate enough that a musician with limited training should be able to play differently by adhering to the particulars, and be able to sound like the original music made from these methodologies. The details are there as examples only, not meant to fully describe every part. The book also features a section in which various musicians answer the same seven questions drawn from the properties.

In writing this book, I changed from a linear perspective that perpetuates a rigid tradition-based understanding to a more useful, flexible and accurate ontological one. I use the term free music as an umbrella term in place of the many terms that signify a period or specific body of work, all of which were lumped together under the term "jazz" and then shuttled away. I blame this syndrome on the jazz industry, which has consistently devalued, maligned, disregarded, ignored, or relegated free music to the lowest place, assuming it to be unsellable. Ironically, innovation - the very thing that makes all of this music historically significant - is exactly what devalues it by industry and institutional standards.

Rather than waste my time fighting this revisionist and ignorant perspective, I chose to not use jazz as a name to describe any material in my book. I use methodology because free music has formal elements and informal ones, each reliant on the other to become the whole. Free music is used as a name for any work in which the artist has set the criteria free from critical approval, industry or institutional oversight; a context in which the artist decides if that criteria was met, in which the player or players have freedom to express themselves through improvisation, using the particulars imbedded within the operational methodology in use. This definition of free music does not exclude improvised music that relies on harmony. Instead it views the use of harmony as a device within a methodology. So Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker are free music musicians, as is Anthony Braxton. In free music, artists synthesize, interpret, and inventmaterial. But invention to some degree is the goal. And invention can be accomplished by the discovery of a new synthesis or new interpretation.

Since I began my playing career in the mid '70s, I have been intrigued by the variety of material and approaches that I encountered. I have never thought to align myself with one sub-group within free music. Instead I wrote early on about having a "repertoire of approaches," and I studied everything I could to make that happen for myself. My point of view was inclusive, but not just for the sake of being open-minded; more specifically, I saw that the bodies of work in free music were similar in a way because they were all so different and different because they were all so similar. As a musician, I understood it as ways to play, not just as things to like or dislike. I tried to learn the material as a way to improvise. I had to understand how each piece within a body of work operated, so that any and all of these parts could be identified as unique within this arena of similar things. Of course, the how-to-play part was not the only important thing. Every bit of material I encountered was made for a reason. I had mine, and I knew what it was. I never thought I needed to latch onto someone else's. Early on I tried to formulate my music in a way in which the composed material informed the improvisation. This meant that I often had to convey this information to the musicians who played my music. While this was never easy, it did help me to learn ways to do it. It is why my own methodology is diverse and the reason I am able to teach.

In 1995, I taught a class in improvisation at the Tufts University Experimental College. In 2000, I was asked to join the faculty at Boston's New England Conservatory of Music, where I have been teaching since. In 2005, I also joined the faculty of the Modern American Music Department at Longy School of Music of Bard College. My work at NEC has mainly been coaching ensembles in the jazz and contemporary improvisation departments and teaching private lessons in improvisation for all instrumentalists. This past year I taught a course called "The Properties of Free Music" at NEC and at Longy, using the technical parts of my book as a course manual. The class is a mix of lecture and workshop; it has given me the chance to see my theories put into practice. My focus with all of this work has been to describe in detail the particular aesthetic and technical elements within the methodologies of Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Anthony Braxton, Eric Dolphy, Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor, and Derek Bailey, among others.

The ability of these amazing young improvising students has made this course a constantly exciting opportunity. The biggest challenge has been to find language that will help them bridge the divide from the jazz pedagogy that focuses on harmonic and modal (scalar) improvising, and provide them with an equivalent in the way of a specific technical description that they can understand and use as a guide for improvisation. To do this, I've had to develop new language and a new pedagogy extracted from explanations made by the artists who made the music, and from my own analysis done through listening and playing the music. My goal has been to provide all the technical material that would enable students to perform this music on the highest level possible. Over the years, my students have consistently amazed me. I feel that many of them could perform with Cecil, Ornette, Braxton, or Evan Parker today and maintain their own voices with all of them. It is my objective as a teacher to instill the ability to comprehend this material in the same way that a student would understand key, meter, or harmony, so that they can walk into a so-called "free" gig and know how to negotiate a balance in the material.

With this understanding, they are prepared to deal with these various ideas of what "free" playing is. They can identify bits of a specific methodology in the process of performing using their knowledge of its specific properties, which are always in play and always adjusted within these methodologies. And with this understanding, they might develop their own use of these properties,or even develop their own methodology. That language, developed in a conservatory setting can also fill the gap that I see in the "theory of improvisation" curricula at many liberal arts colleges. They seem to do a good job preparing students to formulate an aesthetic, but don't offer much in the way of describing how to actually improvise, or how musicians have actually improvised so far. As a meta-methodology, my book suggests a way to construct a methodology by using the properties in the book, all of which are in play and re-configured, recontextualized and processed through synthesis, interpretation in all of free music.

I hope to move the discussion about free music away from critique, opinion, or the philosophy of improvisation by instead describing what has been done so far with a new template. For starters, it must be made clear that free music is not a poor relation to jazz or classical music: It is unique. It is formulated differently and operates differently than any other music, purposely. Free music has specific operational components. My book states clearly that the architectural structure of free music starts its construction with inspiration and finishes it with musical techniques, and that all the bits that comprise those techniques are properties, constants that are reformulated. In other words, each type of property is a building block that is reconfigured in the formulation of a new design.

There is some risk of offending people by codifying material that is thought by some people to be mystical and sacred. When material is made mystical or sacred, it is implied that some people don't deserve access to it. There are those who think that by explaining anything at all technical in nature I am violating an unspoken rule that expects all free music to be original, or robbing people of the chance to make their own technical decisions. Then there are those who think free means 100% invented on the spot, and voice the lowest kind of denial - that free music cannot be explained or taught. These attitudes have done serious damage to the sharing of information about free music. My book describes things that everyone has used; by viewing them in a way that is free of a linear tradition or beyond the shadow of any particular aesthetic perspective, they are all shown to be what they are - material that is used to make music. More information won't kill creativity. Less information always does. Furthermore, the idea that every improviser is a freestanding innovator who shows no reference to any larger methodology has no merit. My book shows that the use of methodology actually allows for individualism within every example given. I have proven this in the classroom, but the enormous amount of free music out there is better proof.

Most professionals are aligned with one existing methodology - or a hybrid methodology - but few are versed in all of them. And even fewer have a methodology that is wholly their own. The examples in my book suggest that maybe no one has invented everything they do. Everyone synthesizes and interprets existing material. But having the ability to read the material being processed through performance is a unique kind of virtuosity. It enhances a player's chances of moving past what has been done into new unchartered territory with a higher percentage of invention. Free music isn't random. It is made of complex materials used in complex situations. Having the ability to play this way moves the music forward. My book shows the connections that make this possible.

Free music is an art form that has been made by individuals who operated without regard for critical or institutional approval, who invented theway they play their instruments and invented platforms on which to play that music, based on whatever aesthetic value they thought mattered to them. The idea of that undiscovered place, one that enlightens someone or enhances the life of the player or listener, is not a finished concept. It's a perpetual frontier. By determining to leave things open-ended in concept and still allow for a better understanding of how things can be done, not just why things should be done, we allow for the possibility that more will emerge. Musical skills are like language. Fluency in speech allows for better expression. An informed imagination combined with a fluent tongue makes for eloquent statements that might help us all to evolve beyond where we are to someplace new again.

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Joe Morris "Joe Morris was born in New Haven, Connecticut on September 13, 1955. At the age of 12 he took lessons on the trumpet for one year. He started on guitar in 1969 at the age of 14. He played his first professional gig later that year. With the exception of a few lessons he is self-taught. The influence of Jimi Hendrix and other guitarists of that period led him to concentrate on learning to play the blues. Soon thereafter his sister gave him a copy of John Coltrane's OM, which inspired him to learn about Jazz and New Music. From age 15 to 17 he attended The Unschool, a student-run alternative high school near the campus of Yale University in downtown New Haven. Taking advantage of the open learning style of the school he spent most of his time day and night playing music with other students, listening to ethnic folk, blues, jazz, and classical music on record at the public library and attending the various concerts and recitals on the Yale campus. He worked to establish his own voice on guitar in a free jazz context from the age of 17. Drawing on the influence of Coltrane, Miles Davis, Cecil Taylor,Thelonius Monk, Ornette Coleman as well as the AACM, BAG, and the many European improvisers of the '70s. Later he would draw influence from traditional West African string music, Messian, Ives, Eric Dolphy, Jimmy Lyons, Steve McCall and Fred Hopkins. After high school he performed in rock bands, rehearsed in jazz bands and played totally improvised music with friends until 1975 when he moved to Boston. Between 1975 and 1978 he was active on the Boston creative music scene as a soloist as well as in various groups from duos to large ensembles. He composed music for his first trio in 1977. In 1980 he traveled to Europe where he performed in Belgium and Holland. When he returned to Boston he helped to organize the Boston Improvisers Group (BIG) with other musicians. Over the next few years through various configurations BIG produced two festivals and many concerts. In 1981 he formed his own record company, Riti, and recorded his first LpWraparound with a trio featuring Sebastian Steinberg on bass and Laurence Cook on drums. Riti records released four more LPs and CDs before 1991. Also in 1981 he began what would be a six year collaboration with the multi-instrumentalist Lowell Davidson, performing with him in a trio and a duo. During the next few years in Boston he performed in groups which featured among others; Billy Bang, Andrew Cyrille, Peter Kowald, Joe McPhee, Malcolm Goldstein, Samm Bennett, Lawrence "Butch" Morris and Thurman Barker. Between 1987 and 1989 he lived in New York City where he performed at the Shuttle Theater, Club Chandelier, Visiones, Inroads, Greenwich House, etc. as well as performing with his trio at the first festival Tea and Comprovisation held at the Knitting Factory. In 1989 he returned to Boston. Between 1989 and 1993 he performed and recorded with his electric trio Sweatshop and electric quartet Racket Club. In 1994 he became the first guitarist to lead his own session in the twenty year history of Black Saint/Soulnote Records with the trio recording Symbolic Gesture. Since 1994 he has recorded for the labels ECM, Hat Hut, Leo, Incus, Okka Disc, Homestead, About Time, Knitting Factory Works, No More Records, AUM Fidelity and OmniTone and Avant. He has toured throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe as a solo and as a leader of a trio and a quartet. Since 1993 he has recorded and/or performed with among others; Matthew Shipp, William Parker, Joe and Mat Maneri, Rob Brown, Raphe Malik, Ivo Pearlman, Borah Bergman, Andrea Parkins, Whit Dickey, Ken Vandermark, DKV Trio, Karen Borca, Eugene Chadborne, Susie Ibarra, Hession/Wilkinson/Fell, Roy Campbell Jr., John Butcher, Aaly Trio, Hamid Drake, Fully Celebrated Orchestra and others. He began playing acoustic bass in 2000 and has since performed with cellist Daniel Levin, Whit Dickey and recorded with pianist Steve Lantner. He has lectured and conducted workshops trroughout the US and Europe. He is a former member of the faculty of Tufts University Extension College and is currently on the faculty at New England Conservatory in the jazz and improvisation department. He was nominated as Best Guitarist of the year 1998 and 2002 at the New York Jazz Awards." ^ Hide Bio for Joe Morris • Show Bio for Marilyn Crispell "Marilyn Crispell is a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music where she studied classical piano and composition, and has been a resident of Woodstock, New York since 1977 when she came to study and teach at the Creative Music Studio. She discovered jazz through the music of John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor and other contemporary jazz players and composers. For ten years she was a member of the Anthony Braxton Quartet and the Reggie Workman Ensemble and has been a member of the Barry Guy New Orchestra and guest with his London Jazz Composers Orchestra, as well as a member of the Henry Grimes Trio, Quartet Noir (with Urs Leimgruber, Fritz Hauser and Joelle Leandre), and Anders Jormin's Bortom Quintet. In 2005 she performed and recorded with the NOW Orchestra in Vancouver, Canada and in 2006 she was co-director of the Vancouver Creative Music Institute and a faculty member at the Banff Centre International Workshop in Jazz. In 2014 she led a three-week music residency at the Atlantic Center For the Arts, New Smyrna Beach, Florida, and in 2016 led a one-week residency at the Conservatory Manuel de Falla in Buenos Aires. Besides working as a soloist and leader of her own groups, Crispell has performed and recorded extensively with well-known players on the American and international jazz scene. She's also performed and recorded music by contemporary composers Robert Cogan, Pozzi Escot, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, Manfred Niehaus and Anthony Davis (including four performances of his opera "X" with the New York City Opera). In addition to playing, she has taught improvisation workshops and given lecture/demonstrations at universities and art centers in the U.S., Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and has collaborated with videographers, filmmakers, dancers and poets. Crispell has been the recipient of three New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship grants (1988-1989, 1994-1995 and 2006-2007), a Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust composition commission (1988-1989), and a Guggenheim Fellowship (2005-2006). In 1996 she was given an Outstanding Alumni Award by the New England Conservatory, and in 2004, was cited as being one of their 100 most outstanding alumni of the past 100 years." ^ Hide Bio for Marilyn Crispell • Show Bio for Charles Downs Charles Downs is a New York City drummer known for band Centipede, influenced by Miles Davis, Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, samba, Afro Cuban, and Caribbean feelings, and points in between. He was a member of Jameel Moondoc's Muntu. He worked with Bobby Zankel, and performed with Cecil Taylor, including being a member of Cecil Taylor's big band. He is a member of Flow Trio with Louie Belogenis and Joe Morris, and Other Dimensions in Music. ^ Hide Bio for Charles Downs • Show Bio for Joe McPhee "Joe McPhee, born November 3,1939 in Miami, Florida, USA, is a multi-instrumentalist, composer, improviser, conceptualist and theoretician. He began playing the trumpet at age eight, taught by his father, himself a trumpet player. He continued on that instrument through his formative school years and later in a U.S. Army band stationed in Germany, at which time he was introduced to performing traditional jazz. Clifford Thornton's Freedom and Unity, released in 1969 on the Third World label, is the first recording on which he appears as a side man. In 1968, inspired by the music of Albert Ayler, he took up the saxophone and began an active involvement in both acoustic and electronic music. His first recordings as leader appeared on the CJ Records label, founded in 1969 by painter Craig Johnson. These include Underground Railroad by the Joe McPhee Quartet (1969), Nation Time (1970), Trinity (1971) and Pieces of Light (1974). In 1975, Swiss entrepreneur Werner X. Uehlinger release Black Magic Man by McPhee, on what was to become Hat Hut Records. In 1981, he met composer, accordionist, performer, and educator Pauline Oliveros, whose theories of "deep listening" strengthened his interests in extended instrumental and electronic techniques. he also discovered Edward de Bono's book Lateral Thinking: A Textbook of Creativity, which presents concepts for solving problems by "disrupting an apparent sequence and arriving at the solution from another angle." de Bono's theories inspired McPhee to apply this "sideways thinking" to his own work in creative improvisation, resulting in the concept of "Po Music." McPhee describes "Po Music" as a "process of provocation" (Po is a language indicator to show that provocation is being used) to "move from one fixed set of ideas in an attempt to discover new ones." He concludes, "It is a Positive, Possible, Poetic Hypothesis." The results of this application of Po principles to creative improvisation can be heard on several Hat Art recordings, including Topology, Linear B, and Oleo & a Future Retrospective. In 1997, McPhee discovered two like-minded improvisers in bassist Dominic Duval and drummer Jay Rosen. The trio premiered at the Vision Jazz Festival in 1998 but the concert went unnoticed by the press. McPhee, Duval, and Rosen therefore decided that an apt title for the group would be Trio X. In 2004 he created Survival Unit III with Fred Lonberg-Holm and Michael Zerang to expand his musical horizons and with a career spanning nearly 50 years and over 100 recordings, he continues to tour internationally, forge new connections while reaching for music's outer limits." ^ Hide Bio for Joe McPhee • Show Bio for Alex Ward "Alex Ward was born in 1974. He is a composer, improviser, and performing musician. His primary instruments are clarinet and guitar, and he has also performed in public and on recordings on alto sax, piano/keyboards, bass guitar, and as a vocalist. He was based in Oxford from 1992-2000, and since then has lived in London. His involvement in freely improvised music dates back to 1986, when he met the guitarist Derek Bailey. As an improviser, he was initially principally a clarinettist (sometimes also playing alto sax), but since 2000 he has also been active as an improvising guitarist. On both instruments, hIs longest-standing collaborations in this field have been with the drummer Steve Noble. From 1993 to 2001, most of his activity as a composer took place in collaboration with Benjamin Hervé, mainly in the context of the rock band Camp Blackfoot. From 2002-2005, his writing was mostly done solo, and was primarily focused on songs. Since 2006, he has been heavily involved in both solo and collaborative composition, predominantly (though not exclusively) of instrumental music. Much of his writing and performing during this time has been done with Dead Days Beyond Help, a duo with drummer Jem Doulton. He also currently leads a number of bands including Predicate, Forebrace, The Alex Ward Quintet/Sextet, and Alex Ward & The Dead Ends. He has been a member of many other groups including ensembles led by Eugene Chadbourne, Simon H. Fell and Duck Baker, and has also done various work as a session musician and in collaboration with other media. Since 2005, he has co-run the label Copepod Records with composer/performer Luke Barlow. He does the recording, mixing and/or mastering of most of his own music, and for many of the groups he plays in." ^ Hide Bio for Alex Ward • Show Bio for Matthew Shipp "Matthew Shipp was born December 7, 1960 in Wilmington, Delaware. He started piano at 5 years old with the regular piano lessons most kids have experienced. He fell in love with jazz at 12 years old. After moving to New York in 1984 he quickly became one of the leading lights in the New York jazz scene. He was a sideman in the David S. Ware quartet and also for Roscoe Mitchell's Note Factory before making the decision to concentrate on his own music. Mr Shipp has reached the holy grail of jazz in that he possesses a unique style on his instrument that is all of his own- and he's one of the few in jazz that can say so. Mr. Shipp has recorded a lot of albums with many labels but his 2 most enduring relationships have been with two labels. In the 1990s he recorded a number of chamber jazz cds with Hatology, a group of cds that charted a new course for jazz that, to this day, the jazz world has not realized. In the 2000s Mr Shipp has been curator and director of the label Thirsty Ear's "Blue Series" and has also recorded for them. In this collection of recordings he has generated a whole body of work that is visionary, far reaching and many faceted." ^ Hide Bio for Matthew Shipp • Show Bio for Ken Vandermark "Born in Warwick, Rhode Island on September 22nd, 1964, Ken Vandermark began studying the tenor saxophone at the age of 16. Since graduating with a degree in Film and Communications from McGill University during the spring of 1986, his primary creative emphasis has been the exploration of contemporary music that deals directly with advanced methods of improvisation. In 1989, he moved to Chicago from Boston, and has worked continuously from the early 1990's onward, both as a performer and organizer in North America and Europe, recording in a large array of contexts, with many internationally renowned musicians (such as Fred Anderson, Ab Baars, Peter Brötzmann, Tim Daisy, Hamid Drake, Terrie Ex, Mats Gustafsson, Devin Hoff, Christof Kurzmann, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Joe McPhee, Paal Nilssen-Love, Paul Lytton, Andy Moor, Joe Morris, and Nate Wooley). His current activity includes work with Made To Break, The Resonance Ensemble, Side A, Lean Left, Fire Room, the DKV Trio, and duos with Paal Nilssen-Love and Tim Daisy; in addition, he is the music director of the experimental Pop band, The Margots. More than half of each year is spent touring in Europe, North America, and Japan, and his concerts and numerous recordings have been critically acclaimed both at home and abroad. In addition to the tenor sax, he also plays the bass and Bb clarinet, and baritone saxophone. In 1999 he was awarded the MacArthur prize for music." ^ Hide Bio for Ken Vandermark • Show Bio for Jack Wright "Jack Wright was born Pittsburgh PA in 1942 and grew up around Philadelphia and Chicago. He began playing saxophone in 1952, with private instruction; also singing in groups large and small through 1964, including a blue grass trio (playing washtub bass), which recorded an album, "Undertaking Bluegrass." After this he ceased playing music. He attended Lafayette College in Easton PA, where he studied European history and literature and graduated 1964; Johns Hopkins University, MA in European history, 1972; taught history at CCNY in NY and then Temple U. 1967-72, after which he left the academic world. In this latter period he was involved in left politics, organizing mainly on a community level, and began to become involved with music again. Described twenty years ago as an "undergrounder by design," Jack Wright is a veteran saxophone improviser based mainly in Philadelphia. He has played mostly on tour through the US and Europe since the early 80s in search of interesting partners and playing situations. Now at 72 he is still the "Johnny Appleseed of Free Improvisation," as guitarist Davey Williams called him in the 80s, on the road as much as ever. And he continues to inspire players outside music-school careerdom, playing sessions with visiting and resident players old and new. His partners over the years are mostly unknown to the music press, and too numerous to mention. He's said to have the widest vocabulary of any, including leaping pitches, punchy, precise timing, sharp and intrusive multiphonics, surprising gaps of silence, and obscene animalistic sounds. A reviewer for the Washington Post said, "In the rarefied, underground world of experimental free improvisation, saxophonist Jack Wright is king"." ^ Hide Bio for Jack Wright • Show Bio for Agusti Fernandez "Agustí Fernández (Palma de Mallorca, 1954), with a perfectly based career and a well-deserved international reputation, is one of the Spanish musicians of major international projection and a world reference in the field of improvised music. Fernández has worked with famous musicians of the free improvisation scene like Peter Kowald, Derek Bailey, Butch Morris, Evan Parker, Barry Guy, Mats Gustafsson, Joel Ryan and Peter Evans a.m.o. He is a member of the Blue Shroud Band, Mats Gustafsson NU Ensemble and Barry Guy New Orquestra. Up to the current date he has published more than 80 CD's He has also worked with the recognised composer of contemporary music Héctor Parra, who composed in collaboration with the pianist FREC, a solo for expanded piano. FREC has been premiered at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in 2013 with the collaboration of the video artist Lucas Caraba. He has conducted various improvised music ensembles like Ad Libitum Ensemble (Varsaw), Free Art Ensemble (Barcelona), Ansambl Studio 6 (Lujbljana) Orquesta FOCO (Madrid), Entenguerengue (Jérez de la Frontera), Impromtu Ensemble (Valencia), etc. Along his professional life Agustí Fernández has received much recognition. His solo for piano "Mutza" presented in New York in 2007 was distinguished by the New York magazine AllAboutJazz as one of 10 best concerts from that year. The CD "Un llamp que no s'acaba mai" on PSI (Agustí Fernández, John Edwards and Mark Sanders) has been distinguished by Allaboutjazz as one of the best 10 cd's in 2009; the CD "Aurora" on Maya Recordings (Agustí Fernandez, Barry Guy and Ramón López) was selected by Cuadernos de Jazz magazine as the best CD in 2007, by the Jaç magazine as the best fourth disc of the history of the Catalan jazz and it was Disc d'émoi (February, 2007) for the French Jazz Magazine. The "Agustí Fernández Aurora Trio" received the second prize at the BMW Welt Jazz Award 2012 celebrated in Münich, Germany. In 2000 he received the Festival Altaveu Award, Sant Boi de Llobregat (Catalonia). In 2001 he received the FAD - Sebastià Guasch Award, Barcelona (Cataluña) with Andrés Corchero por el or the performance "A modo de esperanza". In 2011 Agustí Fernández was the main character of the documentary film "Los dedos huéspedes" by Lucas Caraba, which has been screened in several international festivals of documentary. In 2014 the Ad Libitum Festival (Warsaw) dedicated a monographic edition to celebrate Fernández's 60th Birthday. He's professor of improvised music at the Escuela Superior de Música de Catalunya (ESMUC). He's developing an important teaching activity in the field of improvised music and, among other, he has been teaching in IRCAM in Paris, the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre de Tallin, the Royal Conservatory in The Hague (Holland), the Conservatory in Arhem (Holland), the Taller de Músicos in Gijón (Spain), the Taller de Músics in Barcelona (Spain) and the Conservatorio Superior de Música in Salamanca (Spain)." ^ Hide Bio for Agusti Fernandez • Show Bio for Nate Wooley "Nate Wooley was born in 1974 in Clatskanie, Oregon, a town of 2,000 people in the timber country of the Pacific Northwestern corner of the U.S. He began playing trumpet professionally with his father, a big band saxophonist, at the age of 13. His time in Oregon, a place of relative quiet and slow time reference, instilled in Nate a musical aesthetic that has informed all of his music making for the past 20 years, but in no situation more than his solo trumpet performances. Nate moved to New York in 2001, and has since become one of the most in-demand trumpet players in the burgeoning Brooklyn jazz, improv, noise, and new music scenes. He has performed regularly with such icons as John Zorn, Anthony Braxton, Eliane Radigue, Ken Vandermark, Fred Frith, Evan Parker, and Yoshi Wada, as well as being a collaborator with some of the brightest lights of his generation like Chris Corsano, C. Spencer Yeh, Peter Evans, and Mary Halvorson. Wooley's solo playing has often been cited as being a part of an international revolution in improvised trumpet. Along with Peter Evans and Greg Kelley, Wooley is considered one of the leading lights of the American movement to redefine the physical boundaries of the horn, as well as demolishing the way trumpet is perceived in a historical context still overshadowed by Louis Armstrong. A combination of vocalization, extreme extended technique, noise and drone aesthetics, amplification and feedback, and compositional rigor has led one reviewer to call his solo recordings "exquisitely hostile". In the past three years, Wooley has been gathering international acclaim for his idiosyncratic trumpet language. Time Out New York has called him "an iconoclastic trumpeter", and Downbeat's Jazz Musician of the Year, Dave Douglas has said, "Nate Wooley is one of the most interesting and unusual trumpet players living today, and that is without hyperbole". His work has been featured at the SWR JazzNow stage at Donaueschingen, the WRO Media Arts Biennial in Poland, Kongsberg, North Sea, Music Unlimited, and Copenhagen Jazz Festivals, and the New York New Darmstadt Festivals. In 2011 he was an artist in residence at Issue Project Room in Brooklyn, NY and Cafe Oto in London, England. In 2013 he performed at the Walker Art Center as a featured solo artist. Nate is the curator of the Database of Recorded American Music (www.dramonline.org) and the editor-in-chief of their online quarterly journal Sound American (www.soundamerican.org) both of which are dedicated to broadening the definition of American music through their online presence and the physical distribution of music through Sound American Records. He also runs Pleasure of the Text which releases music by composers of experimental music at the beginnings of their careers in rough and ready mediums." ^ Hide Bio for Nate Wooley • Show Bio for William Parker "William Parker is a bassist, improviser, composer, writer, and educator from New York City, heralded by The Village Voice as, "the most consistently brilliant free jazz bassist of all time." In addition to recording over 150 albums, he has published six books and taught and mentored hundreds of young musicians and artists. Parker's current bands include the Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra, In Order to Survive, Raining on the Moon, Stan's Hat Flapping in the Wind, and the Cosmic Mountain Quartet with Hamid Drake, Kidd Jordan, and Cooper-Moore. Throughout his career he has performed with Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry, Milford Graves, and David S. Ware, among others." ^ Hide Bio for William Parker • Show Bio for Mary Halvorson "One of improvised music's most in-demand guitarists, Mary Halvorson has been active in New York since 2002, following jazz studies at Wesleyan University and the New School. Critics have called her "a singular talent" (Lloyd Sachs, JazzTimes), "NYC's least-predictable improviser" (Howard Mandel, City Arts), "one of the most exciting and original guitarists in jazz-or otherwise" (Steve Dollar, Wall Street Journal), and "one of today's most formidable bandleaders" (Francis Davis, Village Voice). The Philadelphia City Paper's Shaun Brady adds, "Halvorson has been steadily reshaping the sound of jazz guitar in recent years with her elastic, sometimes-fluid, sometimes-shredding, wholly unique style." After three years of study with visionary composer and saxophonist Anthony Braxton, Ms. Halvorson became an active member of several of his bands, including his trio, septet and 12+1tet. To date, she appears on six of Mr. Braxton's recordings. Ms. Halvorson has also performed alongside iconic guitarist Marc Ribot, in his bands Sun Ship and The Young Philadelphians, and with the bassist Trevor Dunn in his Trio-Convulsant. Over the past decade she has worked with such diverse bandleaders as Tim Berne, Taylor Ho Bynum, Tomas Fujiwara, Ingrid Laubrock, Myra Melford, Jason Moran, Joe Morris, Tom Rainey and Mike Reed. As a bandleader and composer, one of Ms. Halvorson's primary outlets is her longstanding trio, featuring bassist John Hébert and drummer Ches Smith. Since their 2008 debut album, Dragon's Head, the band has been recognized as a rising star jazz band by Downbeat Magazine for five consecutive years. Ms. Halvorson's quintet, which adds trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson and alto saxophonist Jon Irabagon to the trio, has released two critically acclaimed albums on the Firehouse 12 label: Saturn Sings and Bending Bridges. Most recently she has added two additional band members-tenor saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock and trombonist Jacob Garchik-to form a septet, featured on her 2013 release Illusionary Sea. Ms. Halvorson also co-leads a longstanding chamber-jazz duo with violist Jessica Pavone, the avant-rock band People and the collective ensembles Thumbscrew and Secret Keeper." ^ Hide Bio for Mary Halvorson • Show Bio for Nicole Mitchell "Nicole Mitchell (b. 1967) is a creative flutist, composer, bandleader and educator. As the founder of Black Earth Ensemble, Black Earth Strings, Ice Crystal and Sonic Projections, Mitchell has been repeatedly awarded by DownBeat Critics Poll and the Jazz Journalists Association as "Top Flutist of the Year" for the last four years (2010-2014). Mitchell's music celebrates African American culture while reaching across genres and integrating new ideas with moments in the legacy of jazz, gospel, experimentalism, pop and African percussion through albums such as Black Unstoppable (Delmark, 2007), Awakening (Delmark, 2011), and Xenogenesis Suite: A Tribute to Octavia Butler (Firehouse 12, 2008), which received commissioning support from Chamber Music America's New Jazz Works. Mitchell formerly served as the first woman president of Chicago's Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), and has been a member since 1995. In recognition of her impact within the Chicago music and arts education communities, she was named "Chicagoan of the Year" in 2006 by the Chicago Tribune. With her ensembles, as a featured flutist and composer, Mitchell has been a highlight at festivals and art venues throughout Europe, the U.S. and Canada. Ms. Mitchell is a recipient of the prestigious Alpert Award in the Arts (2011) and has been commissioned by Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art, the Ravinia Festival, the Chicago Jazz Festival, International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), the Chicago Sinfonietta Orchestra and Maggio Fiorentino Chamber Orchestra (Florence, Italy). In 2009, she created Honoring Grace: Michelle Obama for the Jazz Institute of Chicago. She has been a faculty member at the Vancouver Creative Music Institute, the Sherwood Flute Institute, Banff International Jazz Workshop and the University of Illinois, Chicago. Her work has been featured on National Public Radio, and in magazines including Ebony, Downbeat, JazzIz, Jazz Times, Jazz Wise, and American Legacy. Nicole MItchell is currently a Professor of Music, teaching in "Integrated Composition, Improvisation and Technology," (ICIT) a new and expansively-minded graduate program at the University of California, Irvine. In November 2014, ICIT was approved for the unleashing of a new MA/PhD program, which will be offered starting fall 2015. Mitchell's recent composition, Flight for Freedom for Creative Flute and Orchestra, a Tribute to Harriet Tubman, premiered with the Chicago Composers' Orchestra in December 2011 and was presented again with CCO in May 2014. She was also commisisoned by Chicago Sinfonietta for Harambee: Road to Victory, for Solo Flute, Choir and Orchestra in January 2012. Her latest commission was from the French Ministry of Culture and the Royaumont Foundation in October 2014, which supported the development and French tour of Beyond Black - a collaboration with kora master Ballake Sissoko, Black Earth Ensemble and friends. Currently Mitchell is preparing her next commission supported by the French American Jazz Exchange, entitled Moments of Fatherhood, featuring Black Earth Ensemble and the Parisian chamber group L'Ensemble Laborintus, to premiere at the Sons d'hiver Jazz Festival in late January 2015. Among the first class of Doris Duke Artists (2012), Mitchell works to raise respect and integrity for the improvised flute, to contribute her innovative voice to the jazz legacy, and to continue the bold and exciting directions that the AACM has charted for decades. With contemporary ensembles of varying instrumentation and size (from solo to orchestra), Mitchell's mission is to celebrate the power of endless possibility by "creating visionary worlds through music that bridge the familiar and the unknown." She is endorsed by Powell flutes." ^ Hide Bio for Nicole Mitchell • Show Bio for Katt Hernandez "Katt Hernandez is a composer, improvisor, violinist, producer and artistic researcher. She moved to Stockholm in 2010, and rapidly began working with many artists and new music organizations. In addition to solo violin work, she co-founded The Schematics and Deuterium Quartet, and has worked with a host of musicians and others in Europes's improvised, electronic and experimental music and sound art scenes. After earning a Masters degree in composition from Sweden's Royal College of Music, she began a PhD in Music at Lund university in 2015, and was also employed at the Royal College of Music as part of Klas Nevrin's 3-year research project Music in Disorder. She is currently in the Fire! Orchestra, led by Mats Gustafsson, as well as Lotte Anker's research project Sub-Habitat at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory in Copenhagen. Her work has been featured on festivals, series, museums, conferences and radio stations throughout the world. Before leaving the U.S., Katt was a 13 year veteran of experimental music scenes on the east coast, where she worked with a vast array of musicians, dancers, visual artists, puppeteers, film makers and performance artists, in venues ranging from underground urban art spaces to ivy league concert halls." ^ Hide Bio for Katt Hernandez • Show Bio for Jamie Saft "Jamie Saft (piano, organs, analog synthesis, bass and guitar, steel guitars) is a native of Queens, New York. Since returning to New York in 1993, Saft's stylistic versatility, multi-instrumentalist capabilities, and production skills have been featured with the Beastie Boys, Bad Brains, the B-52's, Laurie Anderson, Bobby Previte, John Zorn, Dave Douglas, Jerry Granelli, Holly Palmer, Marc Ribot's Los Cubanos Postisos, Elysian Fields, Black Beatle, Antony and the Johnsons, Chocolate Genius, JoJo Mayer's Nerve, E-Z Pour Spout, Cuong Vu, Chris Speed Trio Iffy, Jane Ira Bloom, and the Groove Collective. Saft is a mainstay of the downtown scene and a member of bands such as The Beta Popes, Whoopie Pie, Swami LatePlate, The Shakers and Bakers, Kalashnikov, Pramrod Sexena, and John Zorn's Electric Masada. Saft was the pianist for the New York and Paris premiers of John Adams' opera "I Was Looking at the Ceiling and then I Saw the Sky" at Lincoln Center and MC93 Bobingy. Saft has recently composed a number of original film scores and music fortelevision. Recent films scored include the Oscar nominated film"Murderball", Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner "God Grew Tired Of Us",and currently airing HBO documentary "Dear Talula". Saft has alsocontributed score music for Nickelodeon, MTV, and A&E.." ^ Hide Bio for Jamie Saft

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

Joe Morris-author

Contributors:

Marilyn Crispell

Charles Downs

Joe McPhee

Alex Ward

Matthew Shipp

Ken Vandermark

Jack Wright

Simon H Fell

Agusti Fernandez

Nate Wooley

William Parker

Mary Halvorson

Nicole Mitchell

Katt Hernandez

Jamie Saft

Book

Improvised Music

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Top 25 for 2012

Top Sellers and Staff Lists for 2016

Nate Wooley

Search for other titles on the label:

Riti Publishing.

All The Way

(ESP)

| Jeong / Bisio Duo w/ Joe Mcphee / Jay Rosen Morning Bells Whistle Bright (ESP) |

| Kerrod, Jacqueline / Joe Morris Morpeth Contemporary 2024 (Relative Pitch) |

| Christi, Ellen (Christi / Buchanan / Ulrich / Parker / Brown) Instant Reality (Network) |

| Courvoiser, Sylvie / Mary Halvorson Bone Bells (Pyroclastic Records) |

| Zorn, John / Mary Halvorson Quartet The Bagatelles Vol. 1 (Tzadik) |

| Sharp, Elliott (w/ Coleman / Dulberger / Green II / Insell / Jiang / McKenzie / Salomon / Wooley) Hudson River Compositions 1973-74 (zOaR Records) |

| Barker / Parker / Irabagon Bakunawa [VINYL] (Out Of Your Head Records) |

| Crispell, Marilyn / Harvey Sorgen Forest (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Jazzmen, The w/ Joe McPhee Nineteen Sixty-Six (Corbett vs. Dempsey) |

| Thumbscrew (Halvorson / Fujiwara / Formanek Wingbeats (Cuneiform) |

| Parker / Costa / Ernstring Pulsar (NoBusiness) |

| Lowe, Allen And The Constant Sorrow Orchestra Louis Armstrong's America Volume 2 [2 CDs] (ESP) |

| Lowe, Allen And The Constant Sorrow Orchestra Louis Armstrong's America Volume 1 [2 CDs] (ESP) |

| Perelman, Ivo / Nate Wooley Polarity 2 (Burning Ambulance Music) |

| Perelman, Ivo / Nate Wooley Polarity 3 (Burning Ambulance Music) |

| Merega, Giacomo / Joe Morris Opus Dichotomous (Infrequent Seams Records) |

| Reid / Kitamura / Bynum / Morris Geometry of Phenomena (Relative Pitch) |

| Mazurek, Rob & Exploding Star Orchestra Live at Adler Planetarium [VINYL] (International Anthem) |

| Mazurek, Rob & Exploding Star Orchestra Live at Adler Planetarium (International Anthem) |

| Hirsh / Swell / Clouse / Parker Out On A Limb (Soul City Sounds) |

| Barrett, Brad / Taylor Ho Bynum / Joe Morris Geologic Time (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Lowe, Allen And The Constant Sorrow Orchestra Louis Armstrong's America Volume 2 [2 CDs] (ESP) |

| Lowe, Allen And The Constant Sorrow Orchestra Louis Armstrong's America Volume 1 [2 CDs] (ESP) |

| Modney (Modney / Wooley / Gentile / Roberts / Pluta / Symthe / ...) Ascending Primes [2 CDs] (Pyroclastic Records) |

| Die Like A Dog (Brotzmann / Kondo / Parker / Drake) Fragments Of Music, Life And Death Of Albert Ayler [VINYL 2 LPs] (Cien Fuegos) |

| Carter, Daniel / Leo Genovese / William Parker / Francisco Mela Shine Hear Volume 2 (577 Records) |

| Carter, Daniel / Leo Genovese / William Parker / Francisco Mela Shine Hear Volume 2 [VINYL] (577 Records) |

| Parker, William / Ellen Christi Cereal Music (Aum Fidelity) |

| Parker, William / Cooper-Moore / Hamid Drake Heart Trio [VINYL] (Aum Fidelity) |

| Halvorson's, Mary Amaryllis Cloudward (Nonesuch) |

| Parker's, Evan Transatlantic Trance Map Marconi's Drift (False Walls) |

| Borca / R. Brown / W. Parker / Workman / Nicholson / Murphy / Ibarra / Taylor-Baker Good News Blues (NoBusiness) |

| Perelman, Ivo / Matthew Shipp Magical Incantation (Soul City Sounds) |

| Yannatou, Savina / Julius Gabriel / Agusti Fernandez / Barry Guy / Ramon Lopez In the Light Of The Current Myth (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Leandre, Joelle Lifetime Rebel [4 CDs + DVD + BOOKLET] (RogueArt) |

| Modney (Modney / Wooley / Gentile / Roberts / Pluta / Symthe / ...) Ascending Primes [2 CDs] (Pyroclastic Records) |

| Morris, Joe / Jeb Bishop / Nathan McBride Tells Or Terrier (Not Two) |

| Guy, Barry / Ken Vandermark Occasional Poems [2 CDs] (Not Two) |

| Mcphee, Joe / Ken Vandermark Musings of a Bahamian Son: Poems and Other Words (Corbett vs. Dempsey) |

| Futterman, Joel / William Parker Why (Soul City Sounds) |

| Shipp, Matthew The Data [2 CDs] (RogueArt) |

| Deupree, Jerome / Joe Morris / Matthew Shipp Travelogue (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Crispell, Marilyn / Jason Stein / Damon Smith / Adam Shead Spi-Raling Horn (Balance Point Acoustics) |

| Rotem Geffen The Night Is The Night [VINYL] (thanatosis produktion) |

| Mela, Francisco featuring. Leo Genovese / William Parker Music Frees Our Souls, Vol. 3 [VINYL] (577 Records) |

| Rotem Geffen The Night Is The Night (thanatosis produktion) |

| Smith, Wadada Leo / Joe Morris Earth's Frequencies (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Shipp Trio, Matthew (Shipp / Bisio / Baker) New Concepts in Piano Trio Jazz (ESP) |

| Perelman, Ivo Quartet (w/ Shipp / Helias / Rainey) Water Music (RogueArt) |

| NRG Ensemble (directed by Mars Williams) Hold That Thought (Corbett vs. Dempsey) |

| Smith, Ches Laugh Ash (Pyroclastic Records) |

| Wooley, Nate Moths (Editions Verde) |

| Shipp, Matthew / Steve Swell Space Cube Jazz (RogueArt) |

| Perelman, Ivo / Nate Wooley / Mat Moran / Matt Maneri / Fred Lonberg-Holm / Joe Morris Seven Skies Orchestra [2 CDs] (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Tabbal, Tani Quartet (w/ McPhee / Bisio / Siegel) Intentional (Mahakala Music) |

| Wright, Jack What Is What (Relative Pitch) |

| Rothenberg, Ned (w / Courvoisier / Halvorson / Fujiwara) Crossings Four (Clean Feed) |

| Wooley, Nate / Mutual Aid Music Four Experiments [4 CD BOX SET] (Pleasure of the Text Records) |

| Campbell, Roy / William Parker / Zen Matsuura Visitation Of Spirits - the Pyramid Trio Live, 1985 (NoBusiness) |

| Lewis, James Brandon / Red Lily Quintet For Mahalia, With Love [VINYL 2 LPs] (Tao Forms) |

| Lewis, James Brandon / Red Lily Quintet For Mahalia, With Love [2 CDs] (Tao Forms) |

| Shipp, Matthew Trio Circular Temple (ESP-Disk) |

| McPhee, Joe / Mette Rasmussen / Dennis Tyfus Oblique Strategies [VINYL] (Black Truffle) |

| Gjerstad, Frode with Matthew Shipp We Speak (Relative Pitch) |

| Musicworks #145 Summer 2023 [MAGAZINE + CD] (Musicworks) |

| Guy, Barry Blue Shroud Band All This This Here (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Illegal Crowns Unclosing (Out Of Your Head Records) |

| Bromander, Vilhelm In This Forever Unfolding Moment [VINYL] (thanatosis produktion) |

| Bromander, Vilhelm In This Forever Unfolding Moment (thanatosis produktion) |

| Soderberg, Peter String Dialogues (thanatosis produktion) |

| Parker, William Conversations IV [BOOK] (RogueArt) |

| Carter, Daniel / Leo Genovese / William Parker / Francisco Mela Shine Hear, Vol. 1 [VINYL] (577 Records) |

| McPhee, Joe Quartet +1 Kirk Knuffke Keep The Dream Up (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Perelman / Shipp / Cosgrove Live in Carrboro (Soul City Sounds) |

| Mazurek, Rob & Exploding Star Orchestra Lightning Dreamers [VINYL] (International Anthem) |

| Pride, Mike I Hate Work (Rarenoise Records) |

| Amba, Zoh / William Parker / Francisco Mela O Life, O Light Vol. 2 (577 Records) |

| Amba, Zoh / William Parker / Francisco Mela O Life, O Light Vol. 2 [VINYL] (577 Records) |

| Perelman, Ivo / Ray Anderson / Joe Morris / Reggie Nicholson Molten Gold [2 CDs] (Listen! Foundation (Fundacja Sluchaj!)) |

| Swell's, Steve Fire Into Music ( w/ Moondoc / Parker / Drake) For Jemeel: Fire From The Road [3 CDs] (RogueArt) |

| Perelman, Ivo / Matthew Shipp / Joe Morris Shamanism (Mahakala Music) |

| Guy, Barry and Friends Krakow 2018 [5 CD BOX SET] (Not Two) |

| London Jazz Composers Orchestra Krakow 2020 [6 CD BOX SET] (Not Two) |

| Art Ensemble Of Chicago The Sixth Decade: From Paris To Paris [VINYL 2 LPs] (RogueArt) |

| Art Ensemble Of Chicago The Sixth Decade: From Paris To Paris [2 CDs] (RogueArt) |

![BlueRing Improvisers: Materia [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36513.jpg)

![Wheelhouse (Rempis / Adasiewicz / McBride): House And Home [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36462.jpg)

![+DOG+: The Light Of Our Lives [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36009.jpg)

![Parker, Evan / Jean-Marc Foussat: Insolence [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36398.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)