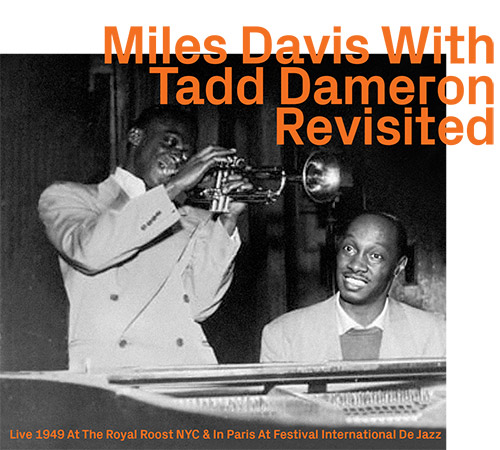

Between his work with Charlie Parker and before his own personal success, trumpeter Miles Davis joined the influential ensemble of pianist, composer and arranger Tadd Dameron, heard in six large ensemble pieces at New York's Royal Roost in 1949, and then in a quintet at the Paris Festival International De Jazz the same year, in both hearing a unique and confident facet to Miles' playing.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Miles Davis-trumpet

Tadd Dameron-piano

Kai Winding-trombone

Benjamin Lundy-tenor saxophone

Sahib Shihab-alto saxophone

Cecil Payne-baritone saxophone

John Collins McCormick-guitar

Curly Russell-double bass

Kenny Clarke-drums

Carlos Vidal-conga

James Moody-tenor saxophone

Barney Spieler-double bass

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

Sound restoration & mastering by Michael Brändli, Hardstudios AG.

UPC: 752156114420

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1144

Squidco Product Code: 32994

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2023

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Track 1-6 recorded live at the Royal Roost, in NYC, on February 19th and 26th, 1949.

Track 7-15 recorded at the Paris Festival Internation De Jazz, at Salle Pleyel, in Paris, France, between May 8th and 15th, 1949.

"We have a curious preference for the old and distressed over the young and fresh. Greek and Roman sculpture needs to be broken for us to appreciate it; we forget that it was once bright, painted, maybe even a little vulgar. We claim to appreciate the "late" works of great artists, often when their most important skills - voice, finger-speed, vision - are already fading. What a privilege it is to hear a great artist in youth and health, brimming with energy. So it is with the recordings here, taken of the 22 year old Miles Davis, working in the company of Tadd Dameron, the most creative arranger of the new bebop style.

Just as the majority of Elvis impersonators tend to mimic the older, overweight, Vegas-bound Elvis, we tend to think of Miles Davis's most defining feature, whether we think of the young, sharp-suited Miles, or the balding, extravagantly dressed wraith he was to become, as the ruined whisper that his voice had become. What a delightful shock to hear him announcing songs to a Parisian audience in clear, bright tones. And then to turn to the music and think, guiltily, of all the times that we've given even tacit support to the notion that Miles was a poor technician, an only awkward exponent of the fast complex transitions of bebop.

Miles's playing in 1949 gives the lie to any notion that he was technically deficient. Apart from anything else, Tadd Dameron expected a certain level of competence in his musicians and when Miles joined the Big Ten for a date at the Royal Roost, the former chicken restaurant at 1580 Broadway that had become known as the "Metropolitan Bopera House", he found himself again in the shadow of another player of exceptional brilliance, as he had been with Dizzy Gillespie in Charlie Parker's group.

Dameron's trumpet player of choice was the slightly older Fats Navarro, a twenty five year old Floridan of complex heritage, composer of "Nostalgia" and possessor of a tight, rounded trumpet tone that seemed destined to become an industry standard for modern jazz.

Navarro, though, was in poor physical and mental health. He had a narcotic addiction and struggled to control his weight, two problems that don't often go together. As a result, and aware that his word-of-mouth reputation was already high, Navarro expected generous payment for his services, and it may well be that Dameron, who was experimenting with a larger ensemble than the usual bebop combo, simply couldn't afford him. It was a happy circumstance, whatever the exact detail, that brought the arranger together with Miles Davis, who had quit Charlie Parker's group, again because he was not being paid by the strung-out saxophonist. Miles, along with John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan, had been experimenting with his own controversially multi-racial and orchestrally minded nonet, a group that aimed to move away from the intensity and speed - sometimes for its own sake - of bebop. Miles was looking for a cool, centred style that mimicked the range of the human voice and his own trumpet tone, which had less high-note sting than was fashionable, but also less of a bass component. The new "cool" jazz was also a chance to move beyond the contrafacts on popular songs that constituted the main diet of bop.

In the spring of 1949, that music was ready to undergo a transformation. Both Miles and Dameron were experimenting with their larger groups, but they were also presented with the opportunity to travel to Paris, a city that still vied with New York for the title of capital of the 20th century, to present a programme of new music at an international jazz festival there. Paris represented many different kinds of freedom to Miles Davis, personal, political, creative, sexual. It was a refuge from American racism and from the narrowness of American music criticism that imposed orthodoxy on a music that thrived on steady evolutionary change.

And yet it was with a relatively conventional group that Miles and Dameron took the stage at Salle Pleyel - where just four years before an American general had dismissed his victorious officers at the end of the war - on May 8, a little under three months after their Royal Roost encounter. Miles is playing with extraordinary freedom and clarity. Right from the opening "Rifftide", all through the numbers he was to play on a succeeding appearance at the same venue, his tone is open, strong and accurate. If again we tend to think of the "typical" Miles Davis sound as muted and husky, it's a revelation to hear him in this character on something like "Good Bait" or Dameron's "Lady Bird". Compare the impact of hearing the young Billie Holiday after long exposure to the wreckage of her later delivery. Almost every uneasy generalisation about Miles's sound and approach crumbles in the face of these remarkable recordings. Dameron was not a great piano stylist and James Moody had not yet emerged as the singular talent and personality he was to become. The Paris performances emphatically belonged to Miles and as the city embraced him, so he, too, blossomed in the spring sunshine. Back in murky February in New York, he had played "April In Paris" with Dameron's "Big Ten", an arrangement that already moves beyond the topline chordal gymnastics of bebop. The month was slightly out, but May in Paris was to be an important moment for Miles, both musically and personally. A few years later, he was to enjoy further revelations in the city as he explored themeless and more abstract playing for a movie soundtrack. He was to enjoy glamour and romance as well, but the French visit was more important to him musically, a neglected highpoint in a career that had already stuttered and would do so again. Fats Navarro, who might well have played a role in both these recordings, is one of jazz's most intriguing and upsetting might-have-beens. By the summer of 1950, he was dead, his lungs weakened by tuberculosis, his frame compromised by heroin addiction. Miles, though he returned to America from his Paris sojourn and a love affair with Juliette Greco that would have been difficult to sustain in the US, depressed and out of work. One version of the next chapter is that out of this slump and a widely publicised arrest for possession of heroin that had cost him work, he began to work on the trumpet sound that would establish his mature reputation. But listening to the Paris tracks it's clear that while the voice did become lower and more softly articulated, it was already there in more than embryo when he took the stage with Dameron, Moody, Barney Spieler and Kenny Clarke. So iconic did Miles become that we forgot to listen to him. These recordings are not just a critical corrective, though. They are an undiluted joy."-Brian Morton, December 31, 2022

Sound restoration & mastering by Michael Brändli, Hardstudios AG.

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Miles Davis "Miles Davis, in full Miles Dewey Davis III, (born May 26, 1926, Alton, Illinois, U.S.-died September 28, 1991, Santa Monica, California), American jazz musician, a great trumpeter who as a bandleader and composer was one of the major influences on the art from the late 1940s. Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, where his father was a prosperous dental surgeon. (In later years he often spoke of his comfortable upbringing, sometimes to rebuke critics who assumed that a background of poverty and suffering was common to all great jazz artists.) He began studying trumpet in his early teens; fortuitously, in light of his later stylistic development, his first teacher advised him to play without vibrato. Davis played with jazz bands in the St. Louis area before moving to New York City in 1944 to study at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School)-although he skipped many classes and instead was schooled through jam sessions with masters such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Davis and Parker recorded together often during the years 1945-48. Davis's early playing was sometimes tentative and not always fully in tune, but his unique, intimate tone and his fertile musical imagination outweighed his technical shortcomings. By the early 1950s Davis had turned his limitations into considerable assets. Rather than emulate the busy, wailing style of such bebop pioneers as Gillespie, Davis explored the trumpet's middle register, experimenting with harmonies and rhythms and varying the phrasing of his improvisations. With the occasional exception of multinote flurries, his melodic style was direct and unornamented, based on quarter notes and rich with inflections. The deliberation, pacing, and lyricism in his improvisations are striking. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Miles Davis • Show Bio for Tadd Dameron "Tadley Ewing Peake Dameron (February 21, 1917 - March 8, 1965) was an American jazz composer, arranger, and pianist. Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Dameron was the most influential arranger of the bebop era, but also wrote charts for swing and hard bop players. The bands he arranged for included those of Count Basie, Artie Shaw, Jimmie Lunceford, Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, and Sarah Vaughan. In 1940-41 he was the piano player and arranger for the Kansas City band Harlan Leonard and his Rockets. He and lyricist Carl Sigman wrote "If You Could See Me Now" for Sarah Vaughan and it became one of her first signature songs. According to the composer, his greatest influences were George Gershwin and Duke Ellington. In the late 1940s, Dameron wrote arrangements for Gillespie's big band, who gave the première of his large-scale orchestral piece Soulphony in Three Hearts at Carnegie Hall in 1948. Also in 1948, Dameron led his own group in New York, which included Fats Navarro; the following year Dameron was at the Paris Jazz Festival with Miles Davis. From 1961 he scored for recordings by Milt Jackson, Sonny Stitt, and Blue Mitchell. Dameron also arranged and played for rhythm and blues musician Bull Moose Jackson. Playing for Jackson at that same time was Benny Golson, who was to become a jazz composer in his own right. Golson has said that Dameron was the most important influence on his writing. Dameron composed several bop and swing standards, including "Hot House", "If You Could See Me Now", "Our Delight", "Good Bait" (composed for Count Basie) and "Lady Bird". Dameron's bands from the late 1940s and early 1950s featured leading players such as Fats Navarro, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, Wardell Gray, and Clifford Brown. In 1956 he led two sessions based on his compositions, released as the 1956 album "Fontainebleau" and the 1957 album "Mating Call". The latter featured John Coltrane. Dameron developed an addiction to narcotics toward the end of his career. He was arrested on drug charges in 1957 and 1958, and served time (1959-60) in a federal prison hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. After his release, Dameron recorded a single notable project as a leader, The Magic Touch, but was sidelined by health problems; he had several heart attacks before dying of cancer in 1965, at the age of 48. He was buried at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York." ^ Hide Bio for Tadd Dameron • Show Bio for Kai Winding "Kai Chresten Winding: May 18, 1922 - May 6, 1983) was a Danish-born American trombonist and jazz composer. He is known for his collaborations with fellow trombonist J. J. Johnson. His version of "More", the theme from the movie Mondo Cane, reached in 1963 number 8 in the Billboard Hot 100 and remained his only entry here. Winding was born in Aarhus, Denmark. His father, Ove Winding was a naturalized U.S. citizen, thus Kai, his mother and sisters, though born abroad were already U.S. citizens. In September 1934, his mother, Jenny Winding, moved Kai and his two sisters, Ann and Alice. Kai graduated in 1940 from Stuyvesant High School in New York City and that same year began his career as a professional trombonist with Shorty Allen's band. Subsequently, he played with Sonny Dunham and Alvino Rey, until he entered the United States Coast Guard during World War II. After the war, Winding was a member of Benny Goodman's orchestra, then Stan Kenton's. He participated in Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949, appearing on four of the twelve tracks, while J. J. Johnson appeared on the other eight, having participated on the other two sessions. In 1954, at the urging of producer Ozzie Cadena, Winding began a long association with Johnson, recording trombone duets for Savoy Records, then Columbia. He experimented with instruments in brass ensembles. The album Jay & Kai + 6 (1956) featured a trombone octet and the trombonium. He composed and arranged many of the works he and Johnson recorded. During the 1960s, Winding began an association with Verve Records and producer Creed Taylor. He released the first version of "Time Is On My Side" in 1963 before it was recorded by Irma Thomas and The Rolling Stones. His best selling recording from this period is "More," the theme from the movie Mondo Cane, which reached number 8 in the Billboard Hot 100 and remained his only entry here. Arranged and conducted by Claus Ogerman, "More" featured what is probably the first appearance of the French electronic music instrument the ondioline on an American recording. Although Winding was credited with playing the ondioline, guitarist Vinnie Bell, who worked on the session, claimed that it was played by Jean-Jacques Perrey, a pioneer of electronic music. Winding experimented with ensembles again, recorded solo albums, and one album of country music with the Anita Kerr Singers. He followed Creed Taylor to A&M/CTI and made more albums with J. J. Johnson. He was a member of the all-star jazz group Giants of Jazz in 1971. His son, Jai Winding, is a keyboardist who has worked as a session musician, writer and producer in Los Angeles. Kai Winding died of a brain tumor in New York City in 1983." ^ Hide Bio for Kai Winding • Show Bio for Sahib Shihab "Sahib Shihab (born Edmund Gregory; June 23, 1925 - October 24, 1989) was an American jazz and hard bop saxophonist (baritone, alto, and soprano) and flautist. He variously worked with Luther Henderson, Thelonious Monk, Fletcher Henderson, Tadd Dameron, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, John Coltrane and Quincy Jones among others. He was born in Savannah, Georgia, United States. Edmund Gregory first played alto saxophone professionally for Luther Henderson aged 13, and studied at the Boston Conservatory, and to perform with trumpeter Roy Eldridge. He played lead alto with Fletcher Henderson in the mid-1940s. He was one of the first jazz musicians to convert to Islam and changed his name in 1947. He belonged to the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam. - American jazz double bassist During the late 1940s, Shihab played with Thelonious Monk, and on July 23, 1951 he recorded with Monk (later issued on the album Genius of Modern Music: Volume 2). During this period, he also appeared on recordings by Art Blakey, Kenny Dorham and Benny Golson. The invitation to play with Dizzy Gillespie's big band in the early 1950s was of particular significance, as it marked Shihab's switch to baritone. On August 12, 1958, Shihab was one of the musicians photographed by Art Kane in his photograph known as "A Great Day in Harlem". In 1959, he toured Europe with Quincy Jones, after becoming disillusioned with racial politics in United States and ultimately settled in Scandinavia, first in Stockholm, Sweden and from 1964 in Copenhagen, Denmark. He worked for Copenhagen Polytechnic and wrote scores for television, cinema and theatre. He wrote a ballet based on the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale, The Red Shoes. In Denmark, Shihab performed with local musicians such as the bass player Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen amongst others. Together with pianist Kenny Drew, he ran a publishing firm and record company. In 1961, he joined the Kenny Clarke/Francy Boland Big Band and remained a member of the band for the 12 years it existed. He married a Danish woman and raised a family in Europe. In the Eurovision Song Contest 1966, Shihab accompanied Lill Lindfors and Svante Thuresson on stage for the Swedish entry "Nygammal Vals". In 1973, Shihab returned to the United States for a three-year hiatus, working as a session musician for rock and pop artists and undertaking work as a copyist for local musicians. He spent his remaining years between New York and Copenhagen and played in a partnership with Art Farmer. He also led his own jazz combo called Dues. From 1986, Shihab was a visiting artist at Rutgers University. Shihab died from liver cancer on October 24, 1989, in Nashville, Tennessee, United States, aged 64." ^ Hide Bio for Sahib Shihab • Show Bio for John Collins McCormick ^ Hide Bio for John Collins McCormick • Show Bio for Kenny Clarke "Kenny Clarke, known among musicians as "Klook" for one of his characteristic drum licks, is truly a jazz pioneer. He was a leader in the rhythmic advances that signaled the beginning of the modern jazz era, his drum style becoming the sound of bebop and influencing drummers such as Art Blakey and Max Roach. Clarke studied music broadly while in high school, including piano, trombone, drums, vibraphone, and theory. Such versatility of knowledge would later serve him well as a bandleader. Clarke moved to New York in late 1935, where he first began developing his unique approach to the drums, one with a wider rhythmic palette than that of the swing band drummers. Instead of marking the count with the top cymbal, Clarke used counter-rhythms to accent the beat, what became known as "dropping of bombs." He found a kindred spirit in Dizzy Gillespie when they hooked up in Teddy Hill's band in 1939. A key opportunity to further expand his drum language came in late 1940 when he landed a gig in the house band (with Thelonious Monk on piano, and Nick Fenton on bass) at Minton's Playhouse. It was this trio that welcomed such fellow travelers as guitarist Charlie Christian, Gillespie, and a host of others to its nightly jam sessions. These sessions became the primary laboratory for their brand of jazz, which came to be called bebop. A stint in the Army from 1943-46 introduced him to pianist John Lewis. After their discharge he and Lewis joined Gillespie's bebop big band, which gave Clarke his first taste of Paris during a European tour. After returning to New York, he joined the Milt Jackson Quartet, which metamorphosed into the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1952. Though he and Lewis remained friends, Clarke chafed at what he felt was the too-staid atmosphere of the MJQ. In 1956, he migrated to Paris, which became his home for nearly 30 years, working with Jacques Helian's band and backing up visiting U.S. jazz artists. During the years 1960-73, he co-led the major Europe-based jazz big band with Belgian pianist Francy Boland, the Clarke-Boland Big Band. The band featured the best of Europe's jazz soloists, including a number of exceptional U.S. expatriate musicians living in Europe. Among these were saxophonists Johnny Griffin and Sahib Shihab, and trumpeter Idrees Sulieman. After the disbanding of his big band, Clarke found numerous opportunities both on the bandstand and teaching in the classroom. He remained quite active as a freelancer, often working with visiting U.S. jazz musicians, until his death in 1985. In 1988, Clarke was inducted into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame." ^ Hide Bio for Kenny Clarke

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Education

2014 Master of Fine Arts, Sculpture; John Herron School of Art and Design, Indianapolis, IN

2007 Bachelors of Fine Art, Interdisciplinary Studio Art, Sculpture and Drawing; School of Art and Design, Purchase

College, State University of New York, Purchase, NY

2002-03 Studio Art, School of the Museum of Fine Art Boston, Boston MA

Relevant Work Experience

2018-19 - Audio Visual Technician/Preparator, Indianapolis Museum of Fine Art

2017/18 3D Foundation,(F123) Junior, Senior, Graduate Sculpture,(S300/400/500) Herron School of Art and Design,

Indianapolis, IN

2015/16 Mellon Digital Arts Fellow, Marlboro College, Marlboro VT, Sound as Material I & II, Sculpture I, Marlboro

College, Marlboro, VT

2014/15 Sophomore Sculpture (S201/02) Herron School of Art and Design, 3-D Fundamentals of Three Dimensional,

Sound as Material (Rotating Topics in Sculpture) Herron School of Art and Design (F123)

Art Appreciation (ART 110-01), University of Indianapolis

Americorp Public Allies, Big Car Collaborative

Residencies

2014 Artist in Residence, Art Farm Nebraska, Marquette NE

Solo Exhibitions/Public Commission

2018 "Recentering / No Most Fatigue and How to Spend" StorageSpace, Sound and Sculpture Installation

Indianapolis, IN

2017 "Why Not See?" Solo Painting Exhibition, Middle Space Gallery, Indianapolis,IN

2015 "Wood, Metal, Sound" Sound Installation, Drury Gallery, Marlboro, VT

2013 The Daniels Leadership Foundation, Artist (creation/fabrication of sculptural award)

2013 "Flow II", Reconnecting Our Waterways at Big Car, Sound Installation, Indianapolis, IN

2011 "John Collins McCormick Drawings", Friends and Relatives Records; Ypsilanti, MI

2010 "Flow", Space Camp Micro Gallery, Indianapolis, IN

Selected Exhibitions/Performances

2019 "Hacked, Found, Repurposed" Group Show, Center for New Music, San Francisco, CA

2017 Midwest Tour with John Wiese (OH, MI, IN)

2017 Concentration Club (series curator) Middle Space Gallery, Indianapolis, IN

2016 Sound Performance; John Collins McCormick, Feeding Tube Records, Florence, MA

"Noise-Brunch" Firehouse Gallery, Worcester, MA

Sound Performance; John Collins McCormick, Pharmacy, Philadelphia, PA,

Ratchet Series (duo with Aaron Zarzutzki) Cafe Mustache, Chicago, IL

2015 Sound Installation for Summer Solstice, 100 Acres Sculpture Park, Indianapolis Museum of Art

Sound Performance; John Collins McCormick "9 Rules of the Avant-Garde" General Public Collective, Indianapolis,

IN

Performance, Excess Gallery, Bloomington, IN

Performance, Totally Awesome Fest, Ypsilanti, MI

2014 Stop Hate in America; Zine Issue 1, Curated by Nick Hoffman, Eugene, OR

Making Memory; Group Exhibition, Sound Installation, Marsh Gallery, Herron School of Art and Design

Sound Performance; John C McCormick; Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Fine Art Center, Indianapolis, IN

2013 Works for Prepared Library, The Cincinnati Public Library; Cincinnati, OH

Hammer, Anvil, Stirrup: People Make Things That Make Sounds, Group Exhibit, Sound Installation, Lux Center for

the Arts, Lincoln, NE

The Wanderer Project; Transmediale Festival, Group Exhibit, Photography; Berlin, Germany

"Dum Dum Zine", Drawings, L.A. Zine Fest; Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA

2012 Sound Performance; Sky Thing; Indy Indie Artist Gallery; Indianapolis, IN

Sound Performance, (D)(B)(H); Dreamland Theater, Ypsilanti, MI

Sound Performance, Sky Thing; The Hideout; Chicago, IL

Drawing Exhibit, "Systemic Abstraction"; The Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Fort Wayne, IN,

Drawing Exhibit, "EX: Collaborative Creation", International Arts Movement; New York City, NY,

Drawing, "Quickest Flippest" Zine; Issues #1,2; Eugene, OR

2011 Drawing zine "Book Store"; Drift Station; Lincoln, NE,

Group Drawing Exhibit, "Psychogenic Fugue"; House Bar; Bloomington, IN,

Colorless Green Ideas; (Zine) Issues #9,10; London, England,

Sound Performance; Sky Thing; Totally Awesome Fest 7;Ypsilianti, MI,

Sound Performance; Madame Gallery; Minneapolis, MN,

Sound Performance; Myopic Books; Chicago, IL

2010 Sound Performance; Sky Thing; It Looks Like It's Open; Columbus, OH

Sound Performance; Roots and Culture; Chicago, IL

Sound Performance; Big Car; Indianapolis, IN

2009 "Drippy-Droppy, Lovebugs, Haters and Couch Potaters"; Artlink Fort Wayne, IN

Pro You Zine Release; Fort Wayne Museum of Art; Fort Wayne, IN

Sound Performance; Sky Thing and The Fort Wayne Ballet w/ David Ingram, Fort Wayne, IN

Selected Bibliography

2012 David Winship, "John Collins McCormick Mysteries of the Ordinary" MinimalExposition.Blogspot.com April 7

James Payne, "John Collins McCormick's Line Drawings" BeautifulDecay.com March 26

Jack Chuter, "Garbage Strike" Attnmagazine.co.uk July 31

2011 Demian Johnston, "Cooler Heads Prevail" DeadFormats.Blogspot.com December 15

2010 Dan Swartz "Populous" Fort Wayne Reader, February 202009 Dan Swartz "Pro You" Fort Wayne Reader, May

18

Discography

2019 Trapping Configuration; Audio Recording, Solo, Eminent Observer, Cincinatti, OH

Ad for Nails; Audio Recording, Solo, Gilgongo Records, Tempe, AZ

2018 One Bone in the Arm; Audio Recording, Solo, Pan y Rosas Discos, net label, Digital Release Chicago, IL. No

Most Fatigue; Audio Recording, Solo, Impulsive Habitat net label, Digital Release, Lisbon Portugal.

2016 Pluperfect; Audio Recording, duo w/ Ben Bennett, Eh? Recordings, San Francisco, CA

There Never Was An Underground; Audio Recording, Solo, Self Released

2015 Icky Vicky; Audio Recording, trio w/ Andy Israelensen, Katie Kroko, Pan y Rosas Discos net label, Digital

Release, Chicago, IL

2014 Beyond Antibiotics; Audio Recording; (D)(B)(H) sextet w/ Justin Rhody, Marty Belcher, Daniel Wick, Joe Stone,

Chris Rall, Human Conduct Records, St. Louis, MO

2013 Lisa's Hat; Audio Recording; Sky Thing, solo, Faux Pas Recordings; North Hampton, MA Virgin Journalist;

Audio Recording; Sky Thing; quartet w/ Stephen Peck, Megan Mirro, Justin Rhody, Eh? Recordings, San Francisco,

CA

2012 Your Reality Check Bounced; Audio Recording; Sky Thing, FM Dust Recordings; Ann Arbor, MI, Master Pieces

of Objective Reporting; Audio Recording; (D)(B)(H) quartet w/ Marty Belcher, Jay Kreimer, Justin Rhody, Gilgongo

Records; Tempe, AZ

2011 Cooler Heads Prevail; Audio Recording; Sky Thing, Solo, Eggy Records; Portland, OR

Garbage Strike; Audio Recording, Solo, Pan y Rosas Discos net label, Digital Release, Chicago, IL

2010 Howdy Cloud; Audio Recording; Sky Thing, Friends and Relatives Records, Ypsilanti, MI-John Collins McCormick Website (https://johncollinsmccormick.files.wordpress.com/2023/05/john-collins-mccormick-cv.pdf)

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Good Bait 3:23

2. Focus 3:56

3. April In Paris 2:56

4. Webb's Delight 3:38

5. Milano 3:38

6. Casbah 3:37

7. Rifftide 4:34

8. Good Bait 5:48

9. Don't Blame Me 4:19

10. Lady Bird 5:00

11. Wah Hoo 5:32

12. Allen's Alley 4:25

13. Embracable You 4:03

14. Ornithology 3:46

15. All The Things You Are 4:16

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Quintet Recordings

Large Ensembles

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

New in Improvised Music

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![Deupree, Jerome / Sylvie Courvoisier / Lester St. Louis / Joe Morris: Canyon [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36404.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Hemphill Stringtet, The: Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36409.jpg)

![Halvorson, Mary Septet: Illusionary Sea [2 LPS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17952.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Nakayama, Tetsuya: Edo Wan [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36105.jpg)

![Yiyuan, Liang / Li Daiguo: Sonic Talismans [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35957.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)