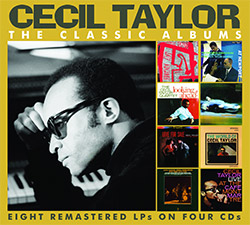

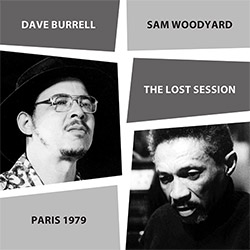

Bringing together two essential and impeccably remastered 1960's Cecil Taylor albums — Cecil Taylor Unit Structures and Cecil Taylor Unit Mixed — presenting both traditional influences and Taylor's unique approaches to modern jazz, featuring two septets with musicians including Jimmy Lyons, Henry Grimes, Archies Shepp, Ted Curson, Andrew Cyrille, Roswell Rudd, Sunny Murray, &c.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Cecil Taylor-piano

Jimmy Lyons-alto saxophone

Ken McIntyre-alto saxophone, bass clarinet

Eddie Gale Stevens Jr.-trumpet

Cecil Taylor-piano

Henry Grimes-double bass

Alan Silva-double bass

Andrew Cyrille-drums

Archie Shepp-tenor saxophone

Ted Curson-trumpet

Roswell Rudd-trombone

Sunny Murray-drums

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156111023

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1110

Squidco Product Code: 29968

Format: CD

Condition: Sale (New)

Released: 2021

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Recorded at Van Gelder Studio, in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, on October 10th, 1961, and May 19th, 1966.

"When Cecil Taylor died in 2018, it was somewhat shocking to reflect that he had begun recording more than 50 years earlier and had released nearly 80 records. It's a measure of his complex reputation that almost none of them have made it into the modern jazz repertory. Taylor was, perhaps, admired more than he was loved. People were afraid of his music and of him. They found a label for it, "atonal", that makes not a whisper of sense. Schoenberg thought the idea of "atonalism" nonsensical because it implied a music without tones; he tried unsuccessfully to replace it with "atonicality", but it never caught on. It doesn't apply to Taylor in either form. His music was polytonal or pantonal, relying on rich clusters of sound or notes played with extreme proximity that the overtones became infinitesimals.

His recording career began in 1956, with one of the most extraordinary debuts in modern music. Charlie Parker had been dead for less than a year. Ornette Coleman had not yet recorded his radical new music. John Coltrane was only just emerging as a significant solo artist. Cecil Taylor was the vanguard of the new modern movement. Jazz Advance found him still covering the work of others, including Monk and Ellington, but also "There's Danger In Your Eyes, Cherie". Two years later, a first glimpse of the mature Taylor came on Looking Ahead! which combined a wonderful fantasia on "Take The 'A' Train" but also an original composition that evoked the cityscape that so influenced him, "Excursion On A Wobbly Rail". No one else plays it. To hear it, you have to listen to Taylor's version.

His emergence as a composer and new star of jazz was complicated. In 1962, three of his compositions were included on an Impulse! record called Into The Hot. It was credited, not to Taylor or the other composer involved, John Carisi, but to arranger Gil Evans, who was considered a safer and more marketable name. The three Taylor tracks also saw the light of day on a compilation titled Mixed in the more appropriate company of Roswell Rudd's group, but this wasn't the only time the industry shied away from his "difficult", "complex" reputation; a later record under Taylor's leadership was reattributed to rising star Coltrane. Even though his name was definitely not in lights, Taylor's music on Into The Hot, included here, was highly significant. "Pots", "Bulbs" and "Mixed" are fascinating for the glimpse they offer of a rapidly evolving vision of modern jazz that blended early jazz, Harlem stride, 20th century art music, not much bebop but lots of singing (Taylor told me that he listened to Billie Holiday every day of his life; he also admired Gloria Gaynor and Beyoncé) into a unique form that positively shimmers with harmonic potential. For which you have to be prepared to listen.

Writing liner notes for a Cecil Taylor record is a daunting business, not because his music is "difficult" or the artist himself "challenging", but because he wrote such good ones himself. When Unit Structures came out [on Blue Note] in 1966, the composer appended a short cover essay called "Sound Structure of Subculture Becoming Major Breath/Naked Fire Gesture". Somewhat like the notes Anthony Braxton sometimes provides for his compositions, the piece didn't necessarily help explain what was going on in the music. For some, it merely added to the confusion. But it also usefully posed a question about what a liner note is for, something that all of us who even occasionally write them should be asking every time.

Taylor's word-pieces, or sound-texts (we can't really call them prose poems) became an important part of his stage presence. They became so important that he once released a whole album of them called Chinampas. They are about as far as possible from the kind of liner note that merely enthuses about the record you're about to hear (Ralph J. Gleason was guilty of many) or tries to set the work in the context of the artist's wider career (something Nat Hentoff was uniquely qualified as a writer/producer to do). Taylor's incantations, like the essay that accompanied Unit Structures was simply a way of preparing the purchaser to listen, which in the modern world is by far the most atrophied of our social skills.

Taylor's essay on the cover of Unit Structures, which came along four years later, was an attempt to prepare the listener for his new music. The music consists of a naturally flowing aggregation of cells which create or propose directions for improvisation, combinations of players, and tonal and rhythmical variations. Can you hum "Enter, Evening" or dance to "Tales (8 Whisps)"? The consensus would be: no. Along with "atonality", Taylor was quickly saddled with a reputation for being unswinging. He often danced before a recital to prove that you could indeed express this music physically. Indeed, almost the only way to appreciate this music is to dance to it, as I invariably do. It isn't a spectacle that needs to be shared with others, but in Mr Taylor's absence can I invite you to find his remarkable essay and let it enter your head before you take the floor. Don't think about this music. Feel it, and let it move you. Literally."-Brian Morton, June 27th, 2020

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

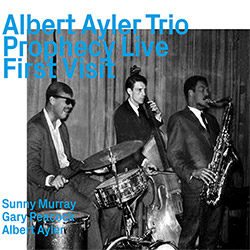

• Show Bio for Cecil Taylor "Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929 - April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet. Classically trained, Taylor is generally acknowledged as having been one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an extremely energetic, physical approach, producing complex improvised sounds, frequently involving tone clusters and intricate polyrhythms. His piano technique has been likened to percussion, for example described as "eighty-eight tuned drums" (referring to the number of keys on a standard piano). He has also been described as "like Art Tatum with contemporary-classical leanings". Taylor was raised in the Corona, Queens neighborhood of New York City. As an only child to a middle-class family, Taylor's mother encouraged him to play music at an early age. He began playing piano at age six and went on to study at the New York College of Music and New England Conservatory. At the New England Conservatory, Taylor majored in composition and arranging. During his time there, he also became familiar with contemporary European art music. Bartok and Stockhausen notably influenced his music. In 1955, Taylor moved from Boston to New York City. He formed a quartet with soprano saxophonist, Steve Lacy, the bassist Buell Neidlinger, and drummer Dennis Charles. Taylor's first recording, Jazz Advance, featured Lacy and was released in 1956. It is described by Cook and Morton in the Penguin Guide to Jazz: "While there are still many nods to conventional post-bop form in this set, it already points to the freedoms in which the pianist would later immerse himself." Taylor's Quartet featuring Lacy also appeared at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival which went on to be made into the album At Newport. He collaborated with saxophonist John Coltrane in 1958 (Stereo Drive, currently available as Coltrane Time). 1950s and 1960s Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Taylor's music grew more complex and moved away from existing jazz styles. Gigs were often hard to come by, and club owners found Taylor's approach to performance (long pieces) unhelpful in conducting business. His 1959 LP Looking Ahead!, showcased his innovation as a creator in comparison to the jazz mainstream. Unlike others at the time, Taylor utilized virtuosic techniques and made swift stylistic shifts from phrase to phrase. These qualities, among others, still remain notable distinctions of Taylor's music today. Landmark recordings, like Unit Structures (1966), also appeared. With 'the Unit', musicians developed often volcanic new forms of conversational interplay. In the early 1960s, an uncredited Albert Ayler worked for a time with Taylor, jamming and appearing on at least one recording, Four, unreleased until 2004. By 1961, Taylor was working regularly with alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, one of his most important and consistent collaborators. Taylor, Lyons and drummer Sunny Murray (and later Andrew Cyrille) formed the core personnel of The Unit, Taylor's primary group effort until Lyons's premature death in 1986. Lyons's playing, strongly influenced by jazz icon Charlie Parker, retained a strong blues sensibility and helped keep Taylor's increasingly avant garde music tethered to the jazz tradition. Solo concerts Taylor began to perform solo concerts in the second half of the sixties. The first known recorded solo performance (by Dutch radio) was 'Carmen With Rings' (59 min.) in De Doelen concert hall in Rotterdam on July 1, 1967. Two days before Taylor had played the same composition in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. Many of the later concerts were released on album and include Indent (1973), side one of Spring of Two Blue-J's (1973), Silent Tongues (1974), Garden (1982), For Olim (1987), Erzulie Maketh Scent (1989) and The Tree of Life (1998). He began to garner critical, if not popular, acclaim, playing for Jimmy Carter on the White House Lawn, lecturing as an in-residence artist at universities, and eventually being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973 and then a MacArthur Fellowship in 1991. 1990s and the Feel Trio Following Lyons's death in 1986 Taylor formed the Feel Trio in the early 1990s with William Parker (bass) and Tony Oxley (drums); the group can be heard on Celebrated Blazons, Looking (Berlin Version) The Feel Trio and the 10-CD set 2 T's for a Lovely T. Compared to his prior small groups with Jimmy Lyons, the Feel Trio had a more abstract approach, tethered less to jazz tradition and more aligned with the ethos of European free improvisation. He also performed with larger ensembles and big-band projects. His extended residence in Berlin in 1988 was extensively documented by the German label FMP, resulting in a massive boxed set of performances in duet and trio with a who's who of European free improvisors, including Oxley, Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Han Bennink, Tristan Honsinger, Louis Moholo, Paul Lovens, and others. Most of his latter day recordings have been put out on European labels, with the exception of Momentum Space (a meeting with Dewey Redman and Elvin Jones) on Verve/Gitanes. The classical label Bridge released his 1998 Library of Congress performance Algonquin, a duet with violinist Mat Maneri. Taylor continued to perform for capacity audiences around the world with live concerts, usually played on his favored instrument, a Bösendorfer piano that features nine extra lower-register keys. A documentary entitled All the Notes, was released on DVD in 2006 by director Chris Felver. Taylor was also featured in an earlier documentary film Imagine the Sound (1981), in which he discusses and performs his music, poetry and dance. 2000s At Moers Festival 2008 Taylor recorded sparingly in the 2000s, but continued to perform with his own ensembles (the Cecil Taylor Ensemble and the Cecil Taylor Big Band) as well as with other musicians such as Joe Locke, Max Roach, and the poet Amiri Baraka. In 2004, the Cecil Taylor Big Band at the Iridium 2005 was nominated a best performance of 2004 by All About Jazz, and the same in 2009 for the Cecil Taylor Trio at the Highline Ballroom in 2009. The trio consisted of Taylor, Albey Balgochian, and Jackson Krall. At time of Taylor's death in 2018A an autobiography, further concerts, and other projects were in the works. In 2010, Triple Point Records released a deluxe limited edition double LP titled Ailanthus/Altissima: Bilateral Dimensions of Two Root Songs, a set of duos with long-time collaborator Tony Oxley that was recorded live at the Village Vanguard in New York City. In 2013, he was awarded the Kyoto Prize for Music. In 2014, his career and 85th birthday were honored at the Painted Bride Art Center in Philadelphia with the tribute concert event "Celebrating Cecil". In 2016 he received a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art entitled Open Plan: Cecil Taylor. Taylor, along with dancer Min Tanaka was the subject of Amiel Courtin-Wilson's 2016 documentary film "The Silent Eye". Ballet and dance In addition to piano, Taylor was always interested in ballet and dance. His mother, who died while he was still young, was a dancer and also played the piano and violin. Taylor once said: "I try to imitate on the piano the leaps in space a dancer makes." He collaborated with dancer Dianne McIntyre in the late 70s and early 80s. In 1979 he also composed and played the music for a twelve-minute ballet "Tetra Stomp: Eatin' Rain in Space", featuring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Heather Watts. Poetry Taylor was a poet, citing Robert Duncan, Charles Olson and Amiri Baraka as major influences. He often integrated his poems into his musical performances, and they frequently appear in the liner notes of his albums. The CD Chinampas, released by Leo Records in 1987, is a recording of Taylor reciting several of his poems, accompanying himself on percussion. Influence and musical style According to Steven Block, free jazz originated with the performances of Cecil Taylor at the Five Spot Cafe in 1957 and Ornette Coleman in 1959. In 1964, Taylor co-founded the Jazz Composers Guild to enhance the working possibilities of avant-garde jazz musicians. Taylor's style and methods have been described as 'constructivist'. Despite Scott Yanow's warning regarding Taylor's "forbidding music": Suffice it to say that Cecil Taylor's music is not for everyone he goes on to praise Taylor's "remarkable technique and endurance," and his "advanced", "radical", "original", and uncompromising "musical vision." This vision is one of Taylor's greatest influences upon others: Playing with Taylor I began to be liberated from thinking about chords. I'd been imitating John Coltrane unsuccessfully and because of that I was really chord conscious. - Archie Shepp, quoted in LeRoi Jones, album liner notes for Four for Trane (Impulse A-71, 1964). Personal life In 1982, jazz critic Stanley Crouch outed Taylor as being gay, prompting an angry response. However, Taylor never denied it. In 1991, Taylor told a New York Times reporter "[s]omeone once asked me if I was gay. I said, 'Do you think a three-letter word defines the complexity of my humanity?' I avoid the trap of easy definition." Taylor moved to Fort Greene, Brooklyn in 1983. Death Taylor died on April 5. 2018 at tbe age of 89." ^ Hide Bio for Cecil Taylor • Show Bio for Jimmy Lyons "Jimmy Lyons (December 1, 1931 - May 19, 1986) was an alto saxophone player. He is best known for his long tenure in the Cecil Taylor Unit. Lyons was the only constant member of the band from the mid-1960s until his death in 1986. Taylor never worked with another musician as frequently as he did with Lyons. Lyons' playing, influenced by Charlie Parker, kept Taylor's avant-garde music tethered to the jazz tradition. Lyons was born in Jersey City, New Jersey and raised there until the age of 9, when his mother moved the family to Harlem and then the Bronx. He obtained his first saxophone in the mid-1940s and took lessons from Buster Bailey. After high school, Lyons was drafted into the United States Army and spent 21 months on infantry duty in Korea. He then spent a year playing in army bands. Once discharged he attended New York University. By the end of the 1950s, Lyons was supporting his interest in music by working for the United States Postal Service. In 1961, Lyons followed Archie Shepp into the saxophone role in the Cecil Taylor Unit. His post-Parker sound and strong melodic sense became a defining part of the sound of that group, from the 1962 Cafe Montmartre sessions onwards. During the 1970s Lyons also ran his own ensemble, with bassoonist Karen Borca and percussionist Paul Murphy. They often performed in the loft jazz movement around Studio Rivbea. Lyons' group and Cecil Taylor Unit continued a parallel development throughour the 1970s and 1980s, often involving the same musicians, including trumpeter Raphe Malik, bassist William Parker and percussionist Murphy. In 1976, Lyons performed in a production of Adrienne Kennedy's A Rat's Mass directed by Cecil Taylor at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in the East Village of Manhattan. Musicians Rashid Bakr, Andy Bey, Karen Borca, David S. Ware, and Raphe Malik also performed in the production. Taylor's production combined the original script with a chorus of orchestrated voices used as instruments. Lyons died from lung cancer in 1986 at the age of 54. He didn't publish many recordings with his own ensemble, though Ayler Records did release a 5-CD box set of recordings from 1972 to 1985." ^ Hide Bio for Jimmy Lyons • Show Bio for Ken McIntyre "Makanda Ken McIntyre (born Kenneth Arthur McIntyre; also known as Ken McIntyre) (September 7, 1931 - June 13, 2001) was an American jazz musician, composer and educator. In addition to his primary instrument, the alto saxophone, he played flute, bass clarinet, oboe, bassoon, double bass, drums, and piano. McIntyre was born in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. His father played mandolin. McIntyre started his musical life on the bugle when he was eight years old, followed by piano. In his teens he discovered the music of Charlie Parker and began playing saxophone at nineteen, then clarinet and flute two years later. In 1953 he served in the Army and played saxophone and piano in Japan. After serving two years in the U.S. Army, he attended the Boston Conservatory where he studied with Gigi Gryce, Charlie Mariano, and Andy McGhee. In 1958 he received a degree in flute and composition with a master's degree the next year in composition. He also received a doctorate (Ed.D.) in curriculum design from the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 1975. In 1960 he recorded as a leader with Eric Dolphy. Beginning the next year, and for the next six years, he taught music in public schools. He took oboe lessons in New York before playing with Bill Dixon, Jaki Byard, and the Jazz Composer's Orchestra. Then he spent three years with pianist Cecil Taylor. During the 1970s he recorded with Nat Adderley and Beaver Harris and in the 1980s with Craig Harris and Charlie Haden. In 1971, he founded the first African American Music program in America at the State University of New York College at Old Westbury, teaching for 24 years. He also taught at Wesleyan University, Smith College, Central State University, Fordham University, and The New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music. In the early 1990s, he changed his name to Makanda Ken McIntyre. While performing in Zimbabwe, a stranger handed him a piece of paper with the word "Makanda" written on it; the word means "many skins" in the Ndebele language and "many heads" in Shona. McIntyre died of a heart attack in New York City, at the age of 69 on June 13, 2001." ^ Hide Bio for Ken McIntyre • Show Bio for Cecil Taylor "Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929 - April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet. Classically trained, Taylor is generally acknowledged as having been one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an extremely energetic, physical approach, producing complex improvised sounds, frequently involving tone clusters and intricate polyrhythms. His piano technique has been likened to percussion, for example described as "eighty-eight tuned drums" (referring to the number of keys on a standard piano). He has also been described as "like Art Tatum with contemporary-classical leanings". Taylor was raised in the Corona, Queens neighborhood of New York City. As an only child to a middle-class family, Taylor's mother encouraged him to play music at an early age. He began playing piano at age six and went on to study at the New York College of Music and New England Conservatory. At the New England Conservatory, Taylor majored in composition and arranging. During his time there, he also became familiar with contemporary European art music. Bartok and Stockhausen notably influenced his music. In 1955, Taylor moved from Boston to New York City. He formed a quartet with soprano saxophonist, Steve Lacy, the bassist Buell Neidlinger, and drummer Dennis Charles. Taylor's first recording, Jazz Advance, featured Lacy and was released in 1956. It is described by Cook and Morton in the Penguin Guide to Jazz: "While there are still many nods to conventional post-bop form in this set, it already points to the freedoms in which the pianist would later immerse himself." Taylor's Quartet featuring Lacy also appeared at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival which went on to be made into the album At Newport. He collaborated with saxophonist John Coltrane in 1958 (Stereo Drive, currently available as Coltrane Time). 1950s and 1960s Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Taylor's music grew more complex and moved away from existing jazz styles. Gigs were often hard to come by, and club owners found Taylor's approach to performance (long pieces) unhelpful in conducting business. His 1959 LP Looking Ahead!, showcased his innovation as a creator in comparison to the jazz mainstream. Unlike others at the time, Taylor utilized virtuosic techniques and made swift stylistic shifts from phrase to phrase. These qualities, among others, still remain notable distinctions of Taylor's music today. Landmark recordings, like Unit Structures (1966), also appeared. With 'the Unit', musicians developed often volcanic new forms of conversational interplay. In the early 1960s, an uncredited Albert Ayler worked for a time with Taylor, jamming and appearing on at least one recording, Four, unreleased until 2004. By 1961, Taylor was working regularly with alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, one of his most important and consistent collaborators. Taylor, Lyons and drummer Sunny Murray (and later Andrew Cyrille) formed the core personnel of The Unit, Taylor's primary group effort until Lyons's premature death in 1986. Lyons's playing, strongly influenced by jazz icon Charlie Parker, retained a strong blues sensibility and helped keep Taylor's increasingly avant garde music tethered to the jazz tradition. Solo concerts Taylor began to perform solo concerts in the second half of the sixties. The first known recorded solo performance (by Dutch radio) was 'Carmen With Rings' (59 min.) in De Doelen concert hall in Rotterdam on July 1, 1967. Two days before Taylor had played the same composition in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. Many of the later concerts were released on album and include Indent (1973), side one of Spring of Two Blue-J's (1973), Silent Tongues (1974), Garden (1982), For Olim (1987), Erzulie Maketh Scent (1989) and The Tree of Life (1998). He began to garner critical, if not popular, acclaim, playing for Jimmy Carter on the White House Lawn, lecturing as an in-residence artist at universities, and eventually being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973 and then a MacArthur Fellowship in 1991. 1990s and the Feel Trio Following Lyons's death in 1986 Taylor formed the Feel Trio in the early 1990s with William Parker (bass) and Tony Oxley (drums); the group can be heard on Celebrated Blazons, Looking (Berlin Version) The Feel Trio and the 10-CD set 2 T's for a Lovely T. Compared to his prior small groups with Jimmy Lyons, the Feel Trio had a more abstract approach, tethered less to jazz tradition and more aligned with the ethos of European free improvisation. He also performed with larger ensembles and big-band projects. His extended residence in Berlin in 1988 was extensively documented by the German label FMP, resulting in a massive boxed set of performances in duet and trio with a who's who of European free improvisors, including Oxley, Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Han Bennink, Tristan Honsinger, Louis Moholo, Paul Lovens, and others. Most of his latter day recordings have been put out on European labels, with the exception of Momentum Space (a meeting with Dewey Redman and Elvin Jones) on Verve/Gitanes. The classical label Bridge released his 1998 Library of Congress performance Algonquin, a duet with violinist Mat Maneri. Taylor continued to perform for capacity audiences around the world with live concerts, usually played on his favored instrument, a Bösendorfer piano that features nine extra lower-register keys. A documentary entitled All the Notes, was released on DVD in 2006 by director Chris Felver. Taylor was also featured in an earlier documentary film Imagine the Sound (1981), in which he discusses and performs his music, poetry and dance. 2000s At Moers Festival 2008 Taylor recorded sparingly in the 2000s, but continued to perform with his own ensembles (the Cecil Taylor Ensemble and the Cecil Taylor Big Band) as well as with other musicians such as Joe Locke, Max Roach, and the poet Amiri Baraka. In 2004, the Cecil Taylor Big Band at the Iridium 2005 was nominated a best performance of 2004 by All About Jazz, and the same in 2009 for the Cecil Taylor Trio at the Highline Ballroom in 2009. The trio consisted of Taylor, Albey Balgochian, and Jackson Krall. At time of Taylor's death in 2018A an autobiography, further concerts, and other projects were in the works. In 2010, Triple Point Records released a deluxe limited edition double LP titled Ailanthus/Altissima: Bilateral Dimensions of Two Root Songs, a set of duos with long-time collaborator Tony Oxley that was recorded live at the Village Vanguard in New York City. In 2013, he was awarded the Kyoto Prize for Music. In 2014, his career and 85th birthday were honored at the Painted Bride Art Center in Philadelphia with the tribute concert event "Celebrating Cecil". In 2016 he received a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art entitled Open Plan: Cecil Taylor. Taylor, along with dancer Min Tanaka was the subject of Amiel Courtin-Wilson's 2016 documentary film "The Silent Eye". Ballet and dance In addition to piano, Taylor was always interested in ballet and dance. His mother, who died while he was still young, was a dancer and also played the piano and violin. Taylor once said: "I try to imitate on the piano the leaps in space a dancer makes." He collaborated with dancer Dianne McIntyre in the late 70s and early 80s. In 1979 he also composed and played the music for a twelve-minute ballet "Tetra Stomp: Eatin' Rain in Space", featuring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Heather Watts. Poetry Taylor was a poet, citing Robert Duncan, Charles Olson and Amiri Baraka as major influences. He often integrated his poems into his musical performances, and they frequently appear in the liner notes of his albums. The CD Chinampas, released by Leo Records in 1987, is a recording of Taylor reciting several of his poems, accompanying himself on percussion. Influence and musical style According to Steven Block, free jazz originated with the performances of Cecil Taylor at the Five Spot Cafe in 1957 and Ornette Coleman in 1959. In 1964, Taylor co-founded the Jazz Composers Guild to enhance the working possibilities of avant-garde jazz musicians. Taylor's style and methods have been described as 'constructivist'. Despite Scott Yanow's warning regarding Taylor's "forbidding music": Suffice it to say that Cecil Taylor's music is not for everyone he goes on to praise Taylor's "remarkable technique and endurance," and his "advanced", "radical", "original", and uncompromising "musical vision." This vision is one of Taylor's greatest influences upon others: Playing with Taylor I began to be liberated from thinking about chords. I'd been imitating John Coltrane unsuccessfully and because of that I was really chord conscious. - Archie Shepp, quoted in LeRoi Jones, album liner notes for Four for Trane (Impulse A-71, 1964). Personal life In 1982, jazz critic Stanley Crouch outed Taylor as being gay, prompting an angry response. However, Taylor never denied it. In 1991, Taylor told a New York Times reporter "[s]omeone once asked me if I was gay. I said, 'Do you think a three-letter word defines the complexity of my humanity?' I avoid the trap of easy definition." Taylor moved to Fort Greene, Brooklyn in 1983. Death Taylor died on April 5. 2018 at tbe age of 89." ^ Hide Bio for Cecil Taylor • Show Bio for Henry Grimes "As of the beginning of 2016, master jazz musician Henry Grimes (acoustic bass, violin, poetry, illustrations) had played more than 615 concerts in 31 countries (including many festivals) since 2003, when he made his astonishing return to the music world after 35 years away. He was born and raised in Philadelphia and attended the Mastbaum School (1949-52) and Juilliard (1952-54). As a youngster in the '50's and early '60's, he came up in the music playing and touring with Willis "Gator Tail" Jackson, Arnett Cobb, "Bullmoose" Jackson, "Little" Willie John, King Curtis, and a number of other great R&B / soul musicians; but drawn to jazz, he went on to play, tour, and record with many great jazz musicians of that era, including Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Benny Goodman, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Haynes, Lee Konitz, Steve Lacy, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Sunny Murray, Sonny Rollins, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, Cecil Taylor, and McCoy Tyner. Sadly, a trip to the West Coast to work with Al Jarreau and Jon Hendricks went awry, leaving Henry in Los Angeles at the end of the '60's with a broken bass he couldn't pay to repair, so he sold it for a small sum and faded away from the music world. Many years passed with nothing heard from him, as he lived in his tiny rented room in an S.R.O. hotel in downtown Los Angeles, working as a manual laborer, custodian, and maintenance man, and writing many volumes of handwritten poetry. He was discovered there by a Georgia social worker in 2002 and was given a bass by William Parker, and after only a few weeks of ferocious woodshedding, Henry emerged from his room to begin playing concerts around Los Angeles and shortly afterwards made a triumphant return to New York City in May, 2003 to play in the Vision Festival. Since then, often working as a leader, he has played, toured, and / or recorded with many of this era's musical and literary heroes, such as Chris Abani, Rashied Ali, Geri Allen, Marshall Allen, Barry Altschul, Fred Anderson, Tatsu Aoki, Newman Taylor Baker, Billy Bang, Harrison Bankhead, Amiri Baraka, Joey Baron, Hamiet Bluiett, Dave Burrell, Roy Campbell Jr., Alex & Nels Cline, Cooper-Moore, Marilyn Crispell, Connie Crothers, Ted Curson, Andrew Cyrille, Thulani Davis, Toi Derricotte, Bill Dixon, Pierre Dorge, Hamid Drake, Paul Dunmall, Cornelius Eady, Kahil El'Zabar, Douglas Ewart, Bobby Few, Charles Gayle, Melvin Gibbs, Yoriyuki Harada, Craig Harris, Graham Haynes, Karma Mayet Johnson, Edward "Kidd" Jordan, Andrew Lamb, Nathaniel Mackey, Maria Mitchell, Nicole Mitchell, Roscoe Mitchell, Elaine Mitchener, Louis Moholo-Moholo, Meredith Monk [recording only], Jemeel Moondoc, Jason Moran, David Murray, Sunny Murray, Amina Claudine Myers, Zim Ngqawana, Kresten Osgood, William Parker, HPrizm (High Priest, Kyle Austin), Odean Pope, Avreeayl Ra, Tomeka Reid, Vernon Reid, Marc Ribot, Matana Roberts, Orphy Robinson, Brandon Ross, Lee Mixashawn Rozie, Mark Sanders, Rasul Siddik, Wadada Leo Smith, Warren Smith, Tyshawn Sorey, Sekou Sundiata, Tani Tabbal, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Aldo Tambellini, Greg Tate, Cecil Taylor (reunion), Chad Taylor, John Tchicai, Pat Thomas, Henry Threadgill, Edwin Torres, Dwight Trible, Jeff "Tain" Watts, Ed Wilkerson Jr., James Zollar, John Zorn, and too many others to list here. In the past few years, Henry has also held a number of residencies and offered workshops and master classes on major campuses, including: Berklee College of Music (Boston); Buffalo Academy for Visual & Performing Arts (upstate New York); CalArts, hosted by Wadada Leo Smith (Valencia, California); the Carlucci School, with Andrew Lamb and Newman Taylor Baker (Portugal); Hamilton College of Performing Arts, with Rashied Ali (upstate New York); Humber College (Toronto); JazzInstitut Darmstadt (Germany); Mills College, hosted by Roscoe Mitchell (Oakland, California); New England Conservatory (Boston, Massachusetts); Scuole Bruscio and Scuole Poschiavo (Switzerland); the University of Gloucestershire at Cheltenham (U.K.); University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois; University of Michigan at Ann Arbor; and several more. Henry can be heard on about a dozen new recordings, made his professional debut on a second instrument (the violin) at the age of 70 alongside Cecil Taylor at Lincoln Center, has seen the publication of the first volume of his poetry, "Signs Along the Road," by a publisher in Cologne, and creates illustrations to accompany his new recordings and publications. He has received many honors in recent years, including four Meet the Composer grants. Mr. Grimes can be heard on 90+ recordings on various labels, including Atlantic, Ayler Records, Blue Note, Columbia, ESP-Disk, ILK Music, Impulse!, JazzNewYork Productions, Pi Recordings, Porter Records, Prestige, Riverside, and Verve. He is the subject of a new biography published in London, "Music to Silence to Music: A Biography of Henry Grimes" by Dr. Barbara Frenz, with a beautiful foreword by Sonny Rollins (http://tinyurl.com/h9f8mo4). And on July 7th, 2016, Henry received a Lifetime Achievement Award and played a full evening of concerts with groups of his own choosing in the Arts for Art / Vision Festival at Judson Memorial Church in New York City , where he had also played and recorded with Albert Ayler's group back in the '60s. Henry Grimes is now a permanent resident of New York City and welcomes students here." ^ Hide Bio for Henry Grimes • Show Bio for Alan Silva "Alan Silva (born Alan Lee da Silva; January 22, 1939 in Bermuda) is an American free jazz double bassist and keyboard player. Silva was born a British subject to an Azorean/Portuguese mother, Irene da Silva, and a black Bermudian father known only as "Ruby". He emigrated to the United States at the age of five with his mother, eventually acquiring U.S. citizenship by the age of 18 or 19. He adopted the stage name of Alan Silva in his twenties. Silva was quoted in a Bermudan newspaper in 1988 as saying that although he left the island at a young age, he always considered himself Bermudian. He was raised in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, where he first began studying the trumpet, and moved on to study the upright bass. Silva is known as one of the most inventive bass players in jazz and has performed with many in the world of avant-garde jazz, including Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, Sunny Murray, and Archie Shepp. Silva performed in 1964's October Revolution in Jazz as a pioneer in the free jazz movement, and for Ayler's Live in Greenwich Village album. He has lived mainly in Paris since the early 1970s, where he formed the Celestrial Communication Orchestra, a group dedicated to the performance of free jazz with various instrumental combinations. In the 1990s he picked up the electronic keyboard, declaring that his bass playing no longer surprised him. He has also used the electric violin and electric sarangi on his recordings. In the 1980s Silva opened a music school I.A.C.P. (Institute for Art, Culture and Perception) in Central Paris, introducing the concept of a Jazz Conservatory patterned after France's traditional conservatories devoted to European classical music epochs. Since around 2000 he has performed more frequently as a bassist and bandleader, notably at New York City's annual Vision Festivals." ^ Hide Bio for Alan Silva • Show Bio for Andrew Cyrille "Andrew Charles Cyrille (born November 10, 1939) is an American avant-garde jazz drummer. Throughout his career, he has performed both as a leader and a sideman in the bands of Walt Dickerson and Cecil Taylor, among others. Cyrille was born on November 10, 1939, in Brooklyn, New York into a Haitian family. He began studying science at St. John's University, but was already playing jazz in the evenings and switched his studies to the Juilliard School. His first drum teachers were fellow Brooklyn-based drummers Willie Jones and Lenny McBrowne; through them, Cyrille met Max Roach. Nonetheless, Cyrille became a disciple of Philly Joe Jones, who in some performances such as Time Waits used Cyrille's drum kit. His first professional engagement was as an accompanist of singer Nellie Lutcher, and he had an early recording session with Coleman Hawkins. Trumpeter Ted Curson introduced him to pianist Cecil Taylor when Cyrille was 18. He joined the Cecil Taylor unit in 1964, and stayed for about 10 years, eventually performing drum duos with Milford Graves. In addition to recording as a bandleader, he has recorded and/or performed with musicians such as David Murray, Irène Schweizer, Marilyn Crispell, Carla Bley, Butch Morris and Reggie Workman among others. Cyrille is currently a member of the group, Trio 3, with Oliver Lake and Reggie Workman." ^ Hide Bio for Andrew Cyrille • Show Bio for Archie Shepp "Archie Shepp (born May 24, 1937) is an American jazz saxophonist. Shepp was born in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, but raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He studied piano, clarinet, and alto saxophone before focusing on tenor saxophone. He occasionally plays soprano saxophone and piano. He studied drama at Goddard College from 1955 to 1959. He played in a Latin jazz band for a short time before joining the band of avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor. Shepp's first recording under his own name, Archie Shepp - Bill Dixon Quartet, was released on Savoy Records in 1962 and featured a composition by Ornette Coleman. Along with John Tchicai and Don Cherry, he was a member of the New York Contemporary Five. John Coltrane's admiration led to recordings for Impulse! Records, the first of which was Four for Trane in 1964, an album of mainly Coltrane compositions on which he was joined by trombonist Roswell Rudd, bassist Reggie Workman and alto player John Tchicai. Shepp participated in the sessions for Coltrane's A Love Supreme in late 1964, but none of the takes he participated in was included on the final LP release (they were made available for the first time on a 2002 reissue). However, Shepp, along with Tchicai and others from the Four for Trane sessions, then recorded Ascension with Coltrane in 1965, and his place alongside Coltrane at the forefront of the avant-garde jazz scene was epitomized when the pair split a record (the first side a Coltrane set, the second a Shepp set) entitled New Thing at Newport released in late 1965.File:Archie Shepp interview 1978.webmPlay media(video) Interview from 1978, Archie Shepp discusses jazz trends, poverty, politics, civil rights, culture and society. In 1965, Shepp released Fire Music, which included the first signs of his developing political consciousness and his increasingly Afrocentric orientation. The album took its title from a ceremonial African music tradition and included a reading of an elegy for Malcolm X. Shepp's 1967 The Magic of Ju-Ju also took its name from African musical traditions, and the music was strongly rooted in African music, featuring an African percussion ensemble. At this time, many African-American jazzmen were increasingly influenced by various continental African cultural and musical traditions; along with Pharoah Sanders, Shepp was at the forefront of this movement. The Magic of Ju-Ju defined Shepp's sound for the next few years: freeform avant-garde saxophone lines coupled with rhythms and cultural concepts from Africa. Shepp was invited to perform in Algiers for the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival of the Organization for African Unity, along with Dave Burrell, Sunny Murray, and Clifford Thornton. This ensemble then recorded several sessions in Paris at the BYG Actuel studios. Shepp continued to experiment into the new decade, at various times including harmonica players and spoken word poets in his ensembles. With 1972's Attica Blues and The Cry of My People, he spoke out for civil rights; the former album was a response to the Attica Prison riots. Shepp also writes for theater; his works include The Communist (1965) and Lady Day: A Musical Tragedy (1972). Both were produced by Robert Kalfin at the Chelsea Theater Center. In 1971, Shepp was recruited to the University of Massachusetts Amherst by Randolph Bromery, beginning a 30-year career as a professor of music. Shepp's first two courses were entitled "Revolutionary Concepts in African-American Music" and "Black Musician in the Theater". Shepp was also a professor of African-American Studies at SUNY in Buffalo, New York. In the late 1970s and beyond, Shepp's career went between various old territories and various new ones. He continued to explore African music, while also recording blues, ballads, spirituals (on the 1977 album Goin' Home with Horace Parlan) and tributes to more traditional jazz figures such as Charlie Parker and Sidney Bechet, while at other times dabbling in R&B, and recording with various European artists including Jasper van't Hof, Tchangodei and Dresch Mih‡ly. Shepp is featured in the 1981 documentary film Imagine the Sound, in which he discusses and performs his music and poetry. Shepp also appears in Mystery, Mr. Ra, a 1984 French documentary about Sun Ra. The film also includes footage of Shepp playing with Sun Ra's Arkestra. Since the early 1990s, he has often played with the French trumpeter Eric Le Lann. In 1993, he worked with Michel Herr to create the original score for the film Just Friends. In 2002, Shepp appeared on the Red Hot Organization's tribute album to Fela Kuti, Red Hot and Riot. Shepp appeared on a track entitled "No Agreement" alongside Res, Tony Allen, Ray Lema, Baaba Maal, and Positive Black Soul. In 2004 Archie Shepp founded his own record label, Archieball, together with Monette Berthomier. The label is located in Paris, France, and includes collaborations with Jacques Coursil, Monica Passos, Bernard Lubat, and Frank Cassenti." ^ Hide Bio for Archie Shepp • Show Bio for Ted Curson "Theodore Curson (June 3, 1935 - November 4, 2012) was an American jazz trumpeter. Curson was born in Philadelphia. He became interested in playing trumpet after watching a newspaper salesman play a silver trumpet. Curson's father, however, wanted him to play alto saxophone like Louis Jordan. When he was ten, he gained his first trumpet. He attended Granoff School of Music in Philadelphia. At the suggestion of Miles Davis, he moved to New York in 1956. He performed and recorded with Cecil Taylor in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His composition "Tears for Dolphy" has been used in numerous films. He was featured in a profile on composer Graham Collier in the 1985 Channel 4 documentary 'Hoarded Dreams' He was a familiar face in Finland, having performed at the Pori Jazz festival every year since it began in 1966. In 2007, he performed at Finland's Independence Day Ball at the invitation of president Tarja Halonen. A longtime resident of Montclair, New Jersey, Curson died from a heart attack in the township on November 4, 2012." ^ Hide Bio for Ted Curson • Show Bio for Roswell Rudd "Roswell Hopkins Rudd, Jr. (born November 17, 1935) is an American jazz trombonist and composer. Although skilled in a variety of genres of jazz (including Dixieland, which he performed while in college) and other genres of music, he is known primarily for his work in free and avant-garde jazz. Since 1962 Rudd has worked extensively with saxophonist Archie Shepp. Rudd was born in Sharon, Connecticut. He attended the Hotchkiss School and graduated from Yale University, where he played with Eli's Chosen Six, a dixieland band of students that Rudd joined in the mid-'50s. The sextet played the boisterous trad jazz style of the day and recorded two albums, including one for Columbia Records. His collaborations with Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, John Tchicai, and Steve Lacy grew out of the lessons learned while playing rags and stomps for drunken college kids in Connecticut. Rudd later taught ethnomusicology at Bard College and the University of Maine. On and off for a period of three decades, he assisted Alan Lomax with his world music song style (Cantometrics) and Global Jukebox projects. In the 1960s, Rudd participated in free jazz recordings such as the New York Art Quartet; the soundtrack for the 1964 movie New York Eye and Ear Control; the album Communications by the Jazz Composer's Orchestra; and in collaborations with Don Cherry, Larry Coryell, Pharoah Sanders, and Gato Barbieri. Rudd has had lifelong friendships with saxophonists Archie Shepp and Steve Lacy and has performed and recorded the music of Thelonious Monk with Lacy. Rudd and his producer and partner Verna Gillis went to Mali in 2000 and 2001. His album MALIcool (2001), a cross-cultural collaboration with kora player Toumani Diabatˇ and other Malian musicians, represented the first time the trombone had been featured in a recording of Malian traditional music. In 2004, he brought his Trombone Shout Band to perform at the 4th Festival au Dˇsert in Essakane, Tombouctou Region, Mali. In 2005, he extended his reach further, recording an album with the Mongolian Buryat Band, a traditional music group of musicians from Mongolia and Buryatia, entitled Blue Mongol. Rudd conducts master classes and workshops both in the United States and around the world." ^ Hide Bio for Roswell Rudd • Show Bio for Sunny Murray "James Marcellus Arthur "Sunny" Murray (born September 21, 1936 in Idabel, Oklahoma) is one of the pioneers of the free jazz style of drumming. Murray spent his youth in Philadelphia before moving to New York City where he began playing with Cecil Taylor: "We played for about a year, just practicing, studying - we went to workshops with Varèse, did a lot of creative things, just experimenting, without a job" He was featured on the influential 1962 concerts in Denmark released as Nefertiti the Beautiful One Has Come. Murray was among the first to forgo the drummer's traditional role as timekeeper in favor of purely textural playing. "Murray's aim was to free the soloist completely from the restrictions of time, and to do this he set up a continual hailstorm of percussion ... continuous ringing stickwork on the edge of the cymbals, an irregular staccato barrage on the snare, spasmodic bass drum punctuation and constant, but not metronomic, use of the sock-cymbal" After his period with Taylor's group, Murray's influence continued as a core part of Albert Ayler's trio who recorded Spiritual Unity: "Sunny Murray and Albert Ayler did not merely break through bar lines, they abolished them altogether." He later recorded under his own name for ESP-Disk and then when he moved to Europe for BYG Actuel." ^ Hide Bio for Sunny Murray

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Pots 5:50

2. Bulbs 6:56

3. Mixed 10:18

4. Steps 10:19

5. Enter Evening (Soft Line Structure) 11:04

6. Unti Structure / As Of Now / Section 17:46

7. Tales (8 Whisps) 7:13

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Free Improvisation

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Septet recordings

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Top Sellers for 2021 by Customer Sales

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Hemphill Stringtet, The: Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36409.jpg)

![Halvorson, Mary Septet: Illusionary Sea [2 LPS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17952.jpg)

![Re-Ghoster Extended: The Zebra Paradox [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36204.jpg)

![FDF Trio: Possibility And Prejudices From Within A Cup [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36205.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Nakayama, Tetsuya: Edo Wan [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36105.jpg)

![Yiyuan, Liang / Li Daiguo: Sonic Talismans [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35957.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)