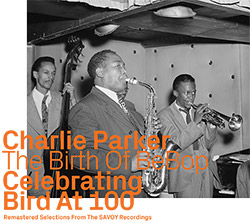

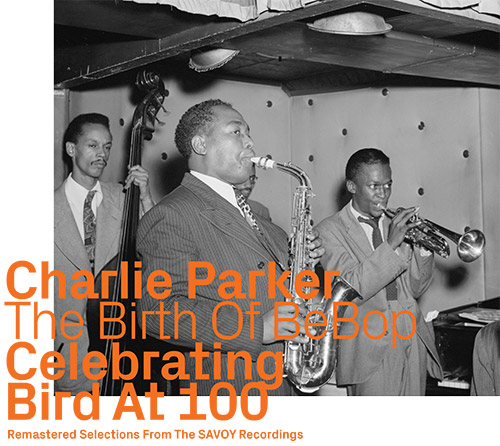

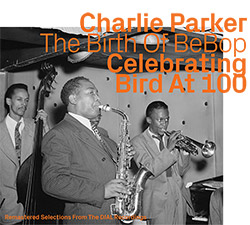

The second of two volumes in celebration of legendary saxophonist Charlie Parker's 100th birthday, here remastering his landmark recordings for the Savoy label in New York City between 1945-48, performing with jazz greats including Bud Powell, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, John Lewis, Curley Russel, Max Roach, &c. for some of be-bop's finest and best known compositions.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Charlie Parker-saxophone

Miles Davis-trumpet

Dizzy Gillespie-trumpet

Sadik Hakim-piano

Curley Russell-bass

Max Roach-drums

Bud Powell-piano

Tommy Potter-bass

Duke Jordan-piano

John Lewis-piano

Al McKibbon-bassist

Joe Harris-drummer

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156111221

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1112

Squidco Product Code: 29381

Format: CD

Condition: Sale (New)

Released: 2020

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

CD Master by Peter Pfister. Tracks 1-4 recorded at WOR Studios, in New York City, New York, on November 26th, 1945.

Tracks 5-7 recorded at Harry Smith Studios, in New York City, New York, on May 8th, 1947.

Tracks 8-11 recorded at United Sound Studios, in Detroit, Michigan, on December 21st, 1947.

Tracks 12-15 recorded at at Harry Smith Studios, New York City, New York, on September 18th, 1948.

Tracks 16-18 recorded at Harry Smith Studios, New York City, New York, on September 24th, 1948.

Tracks 19-23 recorded at Carnegie Hall, in New York City, New York, on September 29th, 1947.

"'Bird was like a bright burning star. If he lived to 90 he couldn't have upset the scene much more, could he?' (Red Callender, quoted in Ira Gitler's book Swing to Bop [Oxford University Press])

In celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth, we naturally recognize Charlie Parker as the prime progenitor of bebop, the revolutionary "new music" of the 1940s. Yet by acknowledging his status as an historical icon in this way, we ironically threaten to isolate his achievement in a distant era, to soften the shock and dilute the substance of his music as the product of a time and circumstances that we no longer identify with. What if, instead, we focus on the rhetorical element of Callender's question? If Parker had lived beyond 1955, would he have continued to innovate, to challenge the conventions of the moment, to upset the scene?

Of course, we are free to speculate on the future of Parker's music had he lived another five, ten, even twenty or thirty years. Consider, thirty more years would have placed him in 1985, at just age 65, certainly within the realm of possibility had he not self-destructed. How would the creative genius of bebop have responded to the freeing implications of Ornette Coleman's music? The electrified jazz-rock hybrid of '70s fusion? Or the gradual but validated interaction of modern classical and improvisational genres? Given his ability to transform Tin Pan Alley songs into anthems of spontaneous recomposition, would he have been similarly attracted to the pop music of Michael Jackson or the Beatles? Is it ridiculous to imagine him wanting to jam with Jimi Hendrix or Prince, as his former sideman Miles Davis did?

In his book A Jazz Retrospect (Crescendo Publishing), British critic Max Harrison gave us the brilliant analogy, "The most urgent of the Dial and especially the Savoy improvisations remind us of the grimacing clay figures the Aztecs used to bury with their dead: a great deal of anguish is expressed in a small space." Similarly, the pianist/singer Mose Allison once said "Bird to me was a blues player caught in the age of anxiety." These comments about anguish and anxiety may reflect upon the personal demons Parker wrestled with in his various addictions, but they also represent the musical struggle between control and ecstasy at Parker's extreme level of genius - a level of infinite complexity rarely encountered in "ordinary" artists. Yet Harrison, among others, has pointed out that the sources of the Savoy repertory in particular are relatively simple and conservative - the largest number of pieces are based on the characteristic blues format, next "I Got Rhythm" changes, and the remainder on several other popular songs - personalized by Parker's intricate, quirky, engaging new themes (or "heads") and intensified by his simultaneous formal ingenuity and emotional impulse.

The blues by nature are fueled by emotion; the evidence that Parker was a consummate blues player, and that so many of his greatest performances created an elaborate transformation of the basic blues format, give his music a timeless quality that transcends the historical/stylistic limitations of the bebop era, and speaks a common language to artists closer to our own experience. Further, pieces like "Bird Gets the Worm" and "Merry-go-Round," which leap directly into dazzling improvi sation without benefit of opening themes, although based on set chord patterns, infer a sense of conceptual expressionist freedom later amplified by Ornette Coleman. But perhaps a deeper parallel exists with Eric Dolphy.

Dolphy's abbreviated career, like Parker's, and their relative ages (one 36, the other 35) are only superficial connections. Rather, like him, his creative edge was the product of brilliantly extended harmonic and rhythmic ideas in a structured context that resulted in a dynamic, dramatic statement. They shared a passionate audacity in their manner of soloing, akin to jumping out of an airplane without a parachute. Yet our perspective of Dolphy shifted depending on the context he was heard in, without changing his point of view; when playing in John Coltrane's group the chord-based albeit ambiguously chromatic quality of his solos contrasted with the more extravagant playing of the leader, as opposed to the radical implications of the same approach in Charles Mingus' more conservative ensemble. Would we have had the same reaction to post-bop, "modern" Parker in different settings?

A revealing artefact that bridges an assumed stylistic generational gap is the 1960 Candid album Newport Rebels, with an ad hoc ensemble put together by Mingus to protest the perceived commercialism by the jazz festival of the same name. Here trumpeter Roy Eldridge and drummer Jo Jones, both nine years older than Bird, share the stage with Mingus, trombonist Jimmy Knepper, and Dolphy. Dolphy and Eldridge might seem incompatible, but they find common ground in the program of standards and blues - Eldridge actually the more adventurous and intense, pushing the expressive tonal envelope in ways reminiscent, in hindsight, of both Rex Stewart and Lester Bowie, and Dolphy emphasizing his own idiosyncratic connection to the blues. One can easily imagine a 40-year-old Parker fitting into this company, not sounding like the Bird of 1947 but investigating new possibilities in a music continually renewed by artists willing to take a risk. Art Lange, Chicago, May 2020

"In 1953 for my 18th birthday my father presented me a small turntable with an integrated loudspeaker to play singles and 10-inch LPs. In addition I got a Charlie Parker 10-inch LP on Jazztone with the California Dial sessions and others. Hearing Parker was my introduction to modern jazz, and his music sounds amazing to this day. Recently I went back to these recordings and discovered that August 29th, 2020 is Parker's 100th Birthday, which created the idea to work on a pair of Remastered/ Revisited CDs for this event. I presented the idea to Bernhard "Benne" Vischer, also about my age, and he reacted within two minutes that he would support the project."-Werner X. Uehlinger, Basel, May 2020

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Charlie Parker Charlie Parker: Songwriter, Saxophonist (1920-1955) Charlie Parker was a legendary Grammy Award-winning jazz saxophonist who, with Dizzy Gillespie, invented the musical style called bop or bebop. From 1935 to 1939, Charlie Parker played the Missouri nightclub scene with local jazz and blues bands. In 1945 he led his own group while performing with Dizzy Gillespie on the side and together they invented bebop. In 1949, Parker made his European debut, giving his last performance several years later. He died a week later on March 12, 1955, in New York City. Early Life Legendary jazz musician Charlie Parker was born Charles Christopher Parker Jr. on August 29, 1920, in Kansas City, Kansas. His father, Charles Parker, was an African American stage entertainer, and his mother, Addie Parker, was a maid-charwoman of Native-American heritage. An only child, Parker moved with his parents to Kansas City, Missouri when he was 7 years old. At the time, the city was a lively center for African-American music, including jazz, blues and gospel. Parker discovered his own talent for music through taking lessons at public schools. As a teen, he played the baritone horn in the school band. By the time Parker was 15, the alto saxophone was his instrument of choice. (Parker's mother had given him a saxophone a few years prior, to help cheer him up after his father had abandoned the family.) While still in school, Parker started playing with bands on the local club scene. He was so enamored of playing the sax that, in 1935, he decided to drop out of school in pursuit of a full-time musical career.Early Musical Career From 1935 to 1939, Parker played the Kansas City, Missouri nightclub scene with local jazz and blues bands, including Buster Professor Smith's band in 1937, and pianist Jay McShann's band in 1938, with which he toured Chicago and New York. In 1939, Parker decided to stick around New York City. There he remained for almost a year, working as a professional musician and jamming for pleasure on the side. After his yearlong stint in the Big Apple, Parker was featured as a regular performer at a Chicago club before deciding to move back to New York permanently. Parker was at first forced to wash dishes in order to get by.Charlie 'Bird' Parker While working in New York, Parker met guitarist Biddy Fleet. It would prove a fruitful encounter. While jamming with Fleet, Parker, who was bored by popular musical conventions, discovered a signature technique that involved playing the higher intervals of a chord for the melody and making changes to back them up accordingly. Later that year Parker heard the news of his father's death and went back to Kansas City, Missouri for the funeral. After the funeral, Parker joined Harlan Leonard's Rockets and stayed in Missouri for the next five months. Parker then decided it was time to head back to New York, where he would rejoin Jay McShann's band. It was with McShann's band, in 1940, that Parker made his first recording. Parker stayed on with the band for four years, during which time he was given several opportunities to perform solo on their recordings. It was also during his time with McShann that Parker earned his famous nickname "Bird," short for "Yardbird." As the story goes, Parker was given the nickname for one of two possible reasons: 1) He was free as a bird, or 2) he accidentally hit a chicken, otherwise known as a yard bird, while driving on tour with the band.Creating Bebop In 1942, burgeoning jazz musicians Gillespie and Thelonious Monk saw Parker perform with McShann's band in Harlem and were impressed by his unique playing style. Later that year, Parker signed up for an eight-month gig with Earl Hines. Then in 1944, Parker joined the Billy Eckstine band. The year 1945 proved to be a landmark one for Parker. At this stage in his career, he is believed to have come into his maturity as a musician. For the first time, he became the leader of his own group while also performing with Dizzy Gillespie on the side. At the end of that year, the two musicians launched a six-week nightclub tour of Hollywood. Together they managed to invent an entirely new style of jazz, commonly known as bop, or bebop. After the joint tour, Parker stayed on in Los Angeles, performing until the summer of 1946. After a period of hospitalization, he returned to New York in January of 1947 and formed a quintet there. With his group, Parker performed some of his best-known and best-loved songs, including his own compositions like "Cool Blues." From 1947 to 1951, Parker performed in ensembles and solo at a variety of venues, including clubs and radio stations. Parker also signed with a few different record labels: From 1945 to 1948, he recorded for Dial. In 1948, he recorded for Savoy Records before signing with Mercury. In 1949, Parker made his European debut at the Paris International Jazz Festival and went on to visit Scandinavia in 1950. Meanwhile, back home in New York, the Birdland Club was being named in his honor. In March of 1955, Parker made his last public performance at Birdland, a week before his death. Throughout his adult life, Parker's battles with heroin addiction, alcoholism and mental illness caused turbulence in his career and personal relationships. By the time Parker married Rebecca Ruffin in 1936, he had already started abusing drugs and alcohol. The couple had two children before divorcing in 1939. In 1942, Parker remarried to Geraldine Scott. Financial stresses created a rift between the couple, and Parker turned to heroin for an escape. He ended up leaving his second wife not long after they were married." ^ Hide Bio for Charlie Parker • Show Bio for Miles Davis "Miles Davis, in full Miles Dewey Davis III, (born May 26, 1926, Alton, Illinois, U.S.-died September 28, 1991, Santa Monica, California), American jazz musician, a great trumpeter who as a bandleader and composer was one of the major influences on the art from the late 1940s. Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, where his father was a prosperous dental surgeon. (In later years he often spoke of his comfortable upbringing, sometimes to rebuke critics who assumed that a background of poverty and suffering was common to all great jazz artists.) He began studying trumpet in his early teens; fortuitously, in light of his later stylistic development, his first teacher advised him to play without vibrato. Davis played with jazz bands in the St. Louis area before moving to New York City in 1944 to study at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School)-although he skipped many classes and instead was schooled through jam sessions with masters such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Davis and Parker recorded together often during the years 1945-48. Davis's early playing was sometimes tentative and not always fully in tune, but his unique, intimate tone and his fertile musical imagination outweighed his technical shortcomings. By the early 1950s Davis had turned his limitations into considerable assets. Rather than emulate the busy, wailing style of such bebop pioneers as Gillespie, Davis explored the trumpet's middle register, experimenting with harmonies and rhythms and varying the phrasing of his improvisations. With the occasional exception of multinote flurries, his melodic style was direct and unornamented, based on quarter notes and rich with inflections. The deliberation, pacing, and lyricism in his improvisations are striking. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Miles Davis • Show Bio for Dizzy Gillespie "John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (/ l spi/; October 21, 1917 Š January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer. He was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuoso style of Roy Eldridge but adding layers of harmonic and rhythmic complexity previously unheard in jazz. His combination of musicianship, showmanship, and wit made him a leading popularizer of the new music called bebop. His beret and horn-rimmed spectacles, his scat singing, his bent horn, pouched cheeks, and his light-hearted personality provided some of bebop's most prominent symbols. In the 1940s Gillespie, with Charlie Parker, became a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz. He taught and influenced many other musicians, including trumpeters Miles Davis, Jon Faddis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Arturo Sandoval, Lee Morgan, Chuck Mangione, and balladeer Johnny Hartman. Scott Yanow wrote, "Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time, Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up being similar to those of Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis's emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated [....] Gillespie is remembered, by both critics and fans alike, as one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time". [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Dizzy Gillespie • Show Bio for Sadik Hakim "Sadik Hakim (born Forrest Argonne Thornton; July 15, 1919 Š June 20, 1983) was an American jazz pianist and composer. Forrest Argonne Thornton was born on July 15, 1919 in Duluth, Minnesota. The name Argonne came from the World War I battle. He was taught music by his grandfather and played locally before moving to Chicago. In Chicago in 1944, Hakim was heard by the tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who took him to New York to be the pianist in his band. He appeared on some Charlie Parker recordings for Savoy Records in the following year. He toured with another saxophonist, Lester Young from 1946 to 1948, including for recordings. He changed his name to Sadik Hakim, a Muslim formulation, in 1947. "In the 1950s Hakim played in Canada with Louis Metcalf, toured with James Moody (1951Š4), and was a member of Buddy Tate's orchestra (1956Š60)." Hakim's debut recording as a leader was in 1962, on an album for Charlie Parker Records that was shared with Duke Jordan. "Around 1966 he moved to Montreal, where he played in nightclubs. He toured Europe for a year, played in a trio at a festival in Duluth (1976), and then returned to New York; he toured Japan in 1979Š80." Hakim returned to recording as a leader in 1973, laying down material that was released by CBC, Progressive, SteepleChase, and Storyville Records. Hakim claimed that he wrote "Eronel", which is usually thought of as a Thelonious Monk composition. Hakim died in New York City on June 20, 1983. He has a daughter, Louize Hakim, who is an apparel designer in Hawaii. Scott Yanow wrote that Hakim "had a particularly unusual boppish style in the '40s, playing dissonant lines, using repetition to build suspense, and certainly standing out from the many Bud Powell impressionists. Later in his career his playing became more conventional." The Penguin Guide to Jazz compared him with Powell, and wrote that Hakim did not have a characteristic playing style." ^ Hide Bio for Sadik Hakim • Show Bio for Curley Russell "Curley Russell was an important bassist in the early years of bebop for he was able to keep up as an accompanist with the rapid tempoes of the time. Never really a soloist (certainly not on the level of an Oscar Pettiford), Russell was a tireless performer who specialized in providing a swinging beat for the lead voices. After playing a bit of trombone, Russell switched to bass and he worked professionally from the age of 18. He was with Don Redman in 1941 and made his recording debut in 1943 with Benny Carter's Orchestra. In 1944 Russell joined Dizzy Gillespie's group and during the next decade he played with the who's who of bop including Charlie Parker (1945, 1948 and 1950), Tadd Dameron (1947-49), Bud Powell, Stan Getz, Buddy DeFranco (1952-53) and the Art Blakey Quintet with Clifford Brown (1954). In addition, Russell recorded with Dexter Gordon, Horace Silver, Coleman Hawkins, Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk among others, although never as a leader. During the mid-to-late 1950's Curly Russell gradually drifted away from jazz into rhythm and blues, finally dropping out of music altogether." ^ Hide Bio for Curley Russell • Show Bio for Max Roach "Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 - August 16, 2007) was an American jazz drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in history. He worked with many famous jazz musicians, including Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Abbey Lincoln, Dinah Washington, Charles Mingus, Billy Eckstine, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, and Booker Little. He was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1992. Roach also co-led a pioneering quintet along with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the percussion ensemble M'Boom. He made numerous musical statements relating to the civil rights movement. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Max Roach • Show Bio for Bud Powell "Earl Rudolph "Bud" Powell (September 27, 1924 Š July 31, 1966) was an American jazz pianist and composer. Along with Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie, Powell was a leading figure in the development of bebop. His virtuosity led many to call him the Charlie Parker of the piano.[citation needed] Powell was also a composer, and many jazz critics credit his works and his playing as having "greatly extended the range of jazz harmony." Powell's father was a stride pianist. Powell started classical piano lessons at the age of five. His teacher, hired by his father, was a West Indian man named Rawlins. At ten, Powell showed interest in the swing music that could be heard all over the neighborhood. He first appeared in public at a rent party, where he mimicked Fats Waller's playing style. The first jazz composition that he mastered was James P. Johnson's "Carolina Shout". Powell's older brother, William, played trumpet and violin, and by the age of 15 Powell was playing in William's band. Powell heard Art Tatum on the radio and tried to match his technique. Powell's younger brother, Richie Powell, was also a noted bebop pianist. In his youth Powell listened to the adventurous performances at Uptown House, a venue near his home. This was where Charlie Parker first appeared as a solo act when he briefly lived in New York. Thelonious Monk played at Uptown House. When Monk met Powell he introduced Powell to musicians who were starting to play bebop at Minton's Playhouse. Monk was a resident pianist, and he presented Powell as his protˇgˇ. Their mutual affection grew, and Monk became Powell's greatest mentor. Powell eagerly experimented with Monk's idea. Monk's composition "In Walked Bud" is a tribute to their time together in Harlem. Powell was engaged in a series of dance bands, his incubation culminating in becoming the pianist for the swing orchestra of Cootie Williams. In late 1943 he was offered the chance to appear at a nightclub with the quintet of Oscar Pettiford and Dizzy Gillespie, but Powell's mother decided he would continue with the more secure job with the popular Williams. Powell was the pianist on a handful of Williams's recording dates in 1944. The last included the first recording of Monk's "'Round Midnight". His job with Williams was terminated in Philadelphia in January 1945. After the band finished for the night, Powell wandered near Broad Street Station and was apprehended, drunk, by the private railroad police. He was beaten by them and incarcerated briefly by the city police. Ten days after his release, his headaches persisted and he was hospitalized at Bellevue, an observation ward, and then in a state psychiatric hospital sixty miles away. He remained there for two and a half months. Powell resumed playing in Manhattan after released. In 1945Š46 he recorded with Frank Socolow, Sarah Vaughan, Dexter Gordon, J. J. Johnson, Sonny Stitt, Fats Navarro, and Kenny Clarke. Powell became known for his sight-reading and his skill at fast tempos. On January 10, 1947, Powell recorded his first session as a leader, which included 8 pieces for De Luxe Records with Max Roach and Curly Russell as accompanists. The recordings were unreleased until 1949, when Roost Records bought the masters and released them on a series of 78 rpm records. Musicologist Guthrie Ramsey wrote of the session that "Powell proves himself the equal of any of the other beboppers in technique, versatility, and feeling." Charlie Parker chose Powell to be his pianist on a May 1947 quintet recording session with Miles Davis, Tommy Potter, and Max Roach; this was the only studio session in which Parker and Powell played together. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Bud Powell • Show Bio for Tommy Potter "Charles Thomas Potter (September 21, 1918 - March 1, 1988) was a jazz double bass player, best known for having been a member of Charlie Parker's "classic quintet", with Miles Davis, between 1947 and 1950. Born in Philadelphia, Potter had first played with Parker in 1944, in Billy Eckstine's band with Dizzy Gillespie, Lucky Thompson and Art Blakey. Potter also performed and recorded with many other notable jazz musicians, including Earl Hines, Artie Shaw, Bud Powell, Count Basie, Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz, Max Roach, Eddie Heywood, Tyree Glenn, Harry "Sweets" Edison, Buck Clayton and Charles Lloyd." ^ Hide Bio for Tommy Potter • Show Bio for Duke Jordan "Although he had a long career, Duke Jordan will always be best known for being pianist with Charlie Parker's classic 1947 quintet. A little earlier, he worked with the Savoy Sultans, Coleman Hawkins, and the Roy Eldridge big band (1946). After his year with Parker (his piano introductions to such songs as "Embraceable You" were classic), Jordan worked with the Sonny Stitt/Gene Ammons quintet (1950-1951) and Stan Getz (1949 and 1952-1953). He started recording as a leader in 1954, debuting his most famous composition, "Jor-Du," the following year. Although he worked steadily during the next few decades (writing part of the soundtrack for the French film Les Liaisons Dangereuses), Jordan was in obscurity until he began recording on a regular basis for Steeplechase in 1973. Duke Jordan, who was married for a time to the talented jazz singer Sheila Jordan, lived in Denmark from 1978 until his death on August 8, 2006. He recorded through the years for Prestige, Savoy, Blue Note, Charlie Parker Records, Muse, Spotlite, and Steeplechase."-Scott Yanow ^ Hide Bio for Duke Jordan • Show Bio for John Lewis "John Aaron Lewis (May 3, 1920 Š March 29, 2001) was an American jazz pianist, composer and arranger, best known as the founder and musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet. John Lewis was born in La Grange, Illinois, and after his parents' divorce moved with his mother, a trained singer, to Albuquerque, New Mexico when he was two months old. She died from peritonitis when he was four and he was raised by his grandmother and great-grandmother. He began learning classical music and piano at the age of seven. His family was musical and had a family band that allowed him to play frequently and he also played in a Boy Scout music group. Even though he learned piano by playing the classics, he was exposed to jazz from an early age because his aunt loved to dance and he would listen to the music she played. He attended the University of New Mexico, where he led a small dance band that he formed and double majored in Anthropology and Music. His piano teacher at the university was Walter Keller, to whom he paid tribute on the title composition of the Modern Jazz Quartet's 1974 album In Memoriam. Eventually, he decided not to pursue Anthropology because he was advised that careers from degrees in the subject did not pay well. In 1942, Lewis entered the army and played piano alongside Kenny Clarke, who influenced him to move to New York once their service was over. Lewis moved to New York in 1945 to pursue his musical studies at the Manhattan School of Music and eventually graduated with a master's degree in music in 1953. Although his move to New York turned his musical attention more towards jazz, he still frequently played and listened to classical works and composers such as Chopin, Bach and Beethoven. Once Lewis moved to New York, Clarke introduced him to Dizzy Gillespie's bop-style big band. He successfully auditioned by playing a song called "Bright Lights" that he had written for the band he and Clarke played for in the army. The tune he originally played for Gillespie, renamed "Two Bass Hit", became an instant success. Lewis composed, arranged and played piano for the band from 1946 until 1948 after the band made a concert tour of Europe. When Lewis returned from the tour with Gillespie's band, he left it to work individually. Lewis was an accompanist for Charlie Parker and played on some of Parker's famous recordings, such as "Parker's Mood" (1948) and "Blues for Alice" (1951), but also collaborated with other prominent jazz artists such as Lester Young, Ella Fitzgerald and Illinois Jacquet. In an article about Dexter Gordon for WorldPress.com, reviewer Ted Panken suggests that ". . . HigginsÕs buoyant ride cymbal and subtle touch propels the soloists through the master take of "Milestones," a John Lewis line for which Miles Davis took credit on his 1947 Savoy debut with Charlie Parker on tenor." Panken seems certain of his claim but does not offer corroboration to a charge that Davis took credit for music that was not his own. Lewis was also part of trumpeter Miles Davis's Birth of the Cool sessions. While in Europe, Lewis received letters from Davis urging him to come back to the United States and collaborate with him, Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan and others on the second session of Birth of the Cool. From when he returned to the U.S. in 1948 through 1949, Lewis joined Davis's nonet and is considered "one of the more prolific arrangers with the 1949 Miles Davis Nonet". For the Birth of the Cool sessions, Lewis arranged "S'il Vous Plait", "Rouge", "Move" and "Budo". Lewis, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, drummer Clarke and bassist Ray Brown had been the small group within the Gillespie big band, and they frequently played their own short sets when the brass and reeds needed a break or even when Gillespie's band was not playing. The small band received a lot of positive recognition and it led to the foursome forming a full-time working group, which they initially called the Milt Jackson Quartet in 1951 but in 1952 renamed the Modern Jazz Quartet. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for John Lewis • Show Bio for Al McKibbon "Al McKibbon (January 1, 1919 - July 29, 2005) was an American jazz double bassist, known for his work in bop, hard bop, and Latin jazz. In 1947, after working with Lucky Millinder, Tab Smith, J. C. Heard, and Coleman Hawkins, he replaced Ray Brown in Dizzy Gillespie's band, in which he played until 1950. In the 1950s he recorded with the Miles Davis nonet, Earl Hines, Count Basie, Johnny Hodges, Thelonious Monk, Mongo Santamaria, George Shearing, Cal Tjader, Herbie Nichols and Hawkins. McKibbon was credited with interesting Tjader in Latin music while he played in Shearing's group. McKibbon has always been highly regarded (among other signs of this regard, he was the bassist for the Giants of Jazz), and continued to perform until 2004. In 1999, the first album in his own name, Tumbao Para Los Congueros De Mi Vida, was released. McKibbon's second album, Black Orchid (Nine Yards Music), was released in 2004 and was recorded at Icon Recording Studios, Hollywood, California. The album was recorded and mixed by studio owner Andrew Troy and Assistant Engineer - Aaron Kaplay, 2nd Assistant Engineer - Pablo Solorzano. He also wrote the Afterword to Raul Fernandez' book, Latin Jazz, part of the Smithsonian Institution's series of exhibitions on jazz." ^ Hide Bio for Al McKibbon • Show Bio for Joe Harris "Following a decade as one of the early bebop drummers, Joe Harris took off for Sweden and never came back. His background also included symphonic percussion instruments such as tympani and xylophone. A drummer from his early teens, Harris began working with bebop maestro Dizzy Gillespie in 1946, working when the datebook called for that outfit through 1948. As the grapevine tells it, Harris was canned from the Gillespie band after getting in a tiff with the leader's wife. Harris balanced jazz with the heavier R&B sounds of tenor saxophonist Arnett Cobb in the late '40s, gigging with singer Billy Eckstine come 1950. The drummer was next associated with both pianist Erroll Garner and Gillespie sidekick James Moody, a saxophonist and flautist, yet basically had a freelance status in Manhattan which included an important house band job at the Apollo Theater. His first tour of Sweden took place in the summer of 1956 in the company of that country's superb trumpeter Rolf Ericson, the season a good one to show off more appealing climactic aspects of the land. Harris' subsequent expatriate status put him in the company of other transplanted instrumentalists including trumpeter Benny Bailey and pianist Freddie Redd -- and as for offstage company, he married a nice Swedish girl. Harris is attributed with a pair of contrasting quotes arising like vapor out of his long gigging background: "The band that plays together, stays together" and "'Dis band should disband." By the '90s, Harris had returned to his native Pittsburgh, residing in the Manchester neighborhood and performing with locals such as pianist Frank Cunimondo."-Eugene Chadbourne ^ Hide Bio for Joe Harris

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Billie's Bounce 3:11

2. Thriving From A Riff 2:58

3. Koko 2:57

4. Meandering 2:36

5. Donna Lee 2:22

6. Cheryl 2:46

7. Buzzy 2:21

8. Another Hair Do 2:41

9. Bluebird 2:53

10. Klaunstance 2:45

11. Bird Gets The Worm 2:38

12. Barbados 2:29

13. Constellation 2:30

14. Parker's Mood 3:03

15. Parker's Mood (alternate take 2) 3:26

16. Marmaduke 2:44

17. Steeplechase 3:06

18. Merry Go Round 2:28

19. A Night In Tunisia 5:07

20. Dizzy Atmosphere 3:36

21. Groovin' High 4:27

22. Confirmation 4:48

23. Koko 4:11

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Quintet Recordings

Sextet Recordings

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Top Sellers for 2020 by Customer Sales

Jazz & Improvisation Based on Compositions

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![Deupree, Jerome / Sylvie Courvoisier / Lester St. Louis / Joe Morris: Canyon [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36404.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Hemphill Stringtet, The: Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36409.jpg)

![Halvorson, Mary Septet: Illusionary Sea [2 LPS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17952.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Nakayama, Tetsuya: Edo Wan [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36105.jpg)

![Yiyuan, Liang / Li Daiguo: Sonic Talismans [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35957.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)