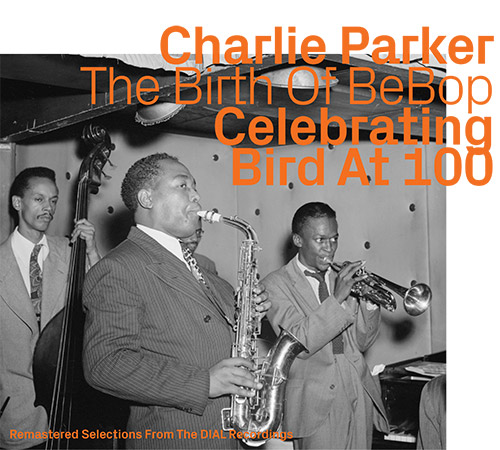

The first of two volumes in celebration of legendary saxophonist Charlie Parker's 100th birthday, here remastering his landmark recordings for the Dial label on the US West Coast between 1946-47, performing with jazz greats including Miles Davis, Lucky Thompson, Erroll Garner, Barney Kessel, Red Calender, JJ Johson, Max Roach, &c. for some of Parker's best known and essential compositions.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Charlie Parker-saxophone

Miles Davis-trumpet

Lucky Thompson-saxophone

Arvin Garrison-guitar

Dodo Marmarosa-piano

Vic McMillan-bass

Roy Porter-drummer

Erroll Garner-piano

Red Callender-bass

Doc West-drummer

Howard McGhee-trumpet

Wardell Gray-saxophone

Duke Jordan-piano

Tommy Potter-bass

Max Roach-drums

J.J. Johnson-trombone

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156111122

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1111

Squidco Product Code: 29380

Format: CD

Condition: Sale (New)

Released: 2020

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

CD Master by Peter Pfister. Tracks 1-4 recorded at Radio Recorders Studios, in Hollywood, California, on March 28th, 1946.

Tracks 5-6 recorded at C.P MacGregor Studio, in Hollywood, California, on February 19th, 1947.

Tracks 7 recorded at C.P MacGregor Studio, in Hollywood, California, February 26th, 1947.

Tracks 8-13 recorded at WOR Studios, in New York City, New York, on October 28th, 1947.

Tracks 14-19 recorded at WOR Studios, in New York City, New York, on November 4th, 1947.

Tracks 20-24 recorded at WOR Studios, in New York City, New York, on December 17th, 1947.

"Despite the time we have had for deep and extensive examination of his life and music since his passing in 1955, in many ways Charlie Parker remains an oxymoron - an unknown entity of mythic proportions. Years of research and analysis have not yet provided the curious listener with a truly satisfying under- standing of all of the parameters of his intensely complicated albeit brief life; speculation, search- ing for an explanation of both his creative genius and his self-destructive decisions, still fuels much of our awareness of the man and his art.

So permit me to indulge in my own speculation concerning a future of which he was deprived, to imagine if Parker had lived beyond a meager 35 years, to allow him a more reasonable life-span and place him in a musical/historical context that in reality evolved under the powerful influence of what he had done, and theorize what might have been.

Suppose we provided Parker with just five more years, postponing his demise until the end of 1960. In August of that year he would have turned 40, sta- tistically speaking still only half a normal lifetime, which reminds us that his position as the primary figure in establishing bebop - the Dial and Savoy recordings - amazingly was achieved while he was just in his late 20s. While various bop practi- tioners continued to sustain the style after 1955, there were already ambitious developments emerging that would supplant bebop as the "new music" of jazz. So the important question we must confront is, would Parker have remained in the bebop idiom, refining, if not fundamentally altering, the music which he helped invent, somewhat along the lines of Thelonious Monk's brilliant but stylistically consistent post-1960 career? Or would these newer alternatives have seduced him into exploring different musical vistas?

Relying on the evidence of his Verve years (which - not counting the Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts which were released on Norman Granz's Mercury, Clef, and ultimately Verve labels starting in 1946 - spanned late '47 to '55), there is nothing to indicate a substantial expansion of Parker's conceptual perspective, despite the opportunity to record with strings, big bands, and latin ensembles. If anything, notwithstanding the high quality of a few studio performances, the Verve recordings display a stylistic entrenchment rather than any potential growth. (Although we must keep in mind that recordings in this era, in part due to label and marketing pressures, can be deceptive as to the actual mindset of creative artists.) Would the possibility of increased commercial success based upon shrewd marketing (requiring simplification) of the bebop brand and Parker's own expanding legend have satisfied his needs at this point in his life? If so, then what we have is a dead end to our speculation of his imaginary future.

One clue we do have to the contrary is the famous report of Parker's unfulfilled desire to study advanced harmony and composition with the adventurous classical composers Edgard Varèse and Stefan Wolpe. In his book On the Music of Stefan Wolpe (Pendragon Press), Austin Clarkson relates that clarinetist Tony Scott introduced Parker to Wolpe, who also worked with jazz figures George Russell, John Carisi, Eddie Sauter, and Eric Dolphy. Varèse, meanwhile, in 1957 collaborated on a never-to-be-completed project with Teo Macero, Hall Overton, and others (including, according to some accounts, Charles Mingus), but previously, in 1954, told Bird biographer Robert Reisner of Parker's request for lessons. Parker's death in 1955 prevented these provocative liaisons.

Parker's role in the birth of bebop was, beyond instrumental virtuosity and sheer exuberance, to provide a challenging new perspective on harmonic and rhythmic complexity. If in the 1950s he was feeling limited by even this level of complexity and sought access to newer, ever more expansive systems of harmonic relationships, an additional five years of life would have put him directly on the path of those developments leading to the jazz revolutions of the 1960s. For example, in 1954 and '55 Mingus was already recording chamber music-influenced small groups with his initial Jazz Workshops; even earlier, in 1952 and '53 Teddy Charles and Hall Overton had ventured into areas of polytonality and formal reorganization. Cecil Taylor made his first recording in 1956 with Steve Lacy in the quartet, even as George Russell was developing his Lydian harmonic system. Ornette Coleman was freeing the soloist's harmonic responsibilities in a post-bop context beginning with his 1958 Contemporary sessions. And in 1960, Eric Dolphy recorded the first three albums under his own name (and a fourth with fellow reedman Ken McIntyre), that same year participating in Gunther Schuller's Third Stream explorations.

Even in one's wildest imagination, it's impossible to conjure up what Charlie Parker might have sounded like in a beyond-bop harmonic context alongside Cecil Taylor (although Taylor's subsequent altoist Jimmy Lyons may be the closest we have to an actual approximation), or negotiating the atonal environment of Schuller's scores. It's enough to speculate on the possibility that this is the direction he would have gone. In that case, he would have influenced the evolution of jazz in the '60s just as he did in the 1940s. It's our loss that we'll never know what it would have sounded like."-Art Lange, Chicago, May 2020

"In 1953 for my 18th birthday my father presented me a small turntable with an integrated loudspeaker to play singles and 10-inch LPs. In addition I got a Charlie Parker 10-inch LP on Jazztone with the California Dial sessions and others. Hearing Parker was my introduction to modern jazz, and his music sounds amazing to this day. Recently I went back to these recordings and discovered that August 29th, 2020 is Parker's 100th Birthday, which created the idea to work on a pair of Remastered/Revisited CDs for this event. I presented the idea to Bernhard "Benne" Vischer, also about my age, and he reacted within two minutes that he would support the project."-Werner X. Uehlinger, Basel, May 2020

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Charlie Parker Charlie Parker: Songwriter, Saxophonist (1920-1955) Charlie Parker was a legendary Grammy Award-winning jazz saxophonist who, with Dizzy Gillespie, invented the musical style called bop or bebop. From 1935 to 1939, Charlie Parker played the Missouri nightclub scene with local jazz and blues bands. In 1945 he led his own group while performing with Dizzy Gillespie on the side and together they invented bebop. In 1949, Parker made his European debut, giving his last performance several years later. He died a week later on March 12, 1955, in New York City. Early Life Legendary jazz musician Charlie Parker was born Charles Christopher Parker Jr. on August 29, 1920, in Kansas City, Kansas. His father, Charles Parker, was an African American stage entertainer, and his mother, Addie Parker, was a maid-charwoman of Native-American heritage. An only child, Parker moved with his parents to Kansas City, Missouri when he was 7 years old. At the time, the city was a lively center for African-American music, including jazz, blues and gospel. Parker discovered his own talent for music through taking lessons at public schools. As a teen, he played the baritone horn in the school band. By the time Parker was 15, the alto saxophone was his instrument of choice. (Parker's mother had given him a saxophone a few years prior, to help cheer him up after his father had abandoned the family.) While still in school, Parker started playing with bands on the local club scene. He was so enamored of playing the sax that, in 1935, he decided to drop out of school in pursuit of a full-time musical career.Early Musical Career From 1935 to 1939, Parker played the Kansas City, Missouri nightclub scene with local jazz and blues bands, including Buster Professor Smith's band in 1937, and pianist Jay McShann's band in 1938, with which he toured Chicago and New York. In 1939, Parker decided to stick around New York City. There he remained for almost a year, working as a professional musician and jamming for pleasure on the side. After his yearlong stint in the Big Apple, Parker was featured as a regular performer at a Chicago club before deciding to move back to New York permanently. Parker was at first forced to wash dishes in order to get by.Charlie 'Bird' Parker While working in New York, Parker met guitarist Biddy Fleet. It would prove a fruitful encounter. While jamming with Fleet, Parker, who was bored by popular musical conventions, discovered a signature technique that involved playing the higher intervals of a chord for the melody and making changes to back them up accordingly. Later that year Parker heard the news of his father's death and went back to Kansas City, Missouri for the funeral. After the funeral, Parker joined Harlan Leonard's Rockets and stayed in Missouri for the next five months. Parker then decided it was time to head back to New York, where he would rejoin Jay McShann's band. It was with McShann's band, in 1940, that Parker made his first recording. Parker stayed on with the band for four years, during which time he was given several opportunities to perform solo on their recordings. It was also during his time with McShann that Parker earned his famous nickname "Bird," short for "Yardbird." As the story goes, Parker was given the nickname for one of two possible reasons: 1) He was free as a bird, or 2) he accidentally hit a chicken, otherwise known as a yard bird, while driving on tour with the band.Creating Bebop In 1942, burgeoning jazz musicians Gillespie and Thelonious Monk saw Parker perform with McShann's band in Harlem and were impressed by his unique playing style. Later that year, Parker signed up for an eight-month gig with Earl Hines. Then in 1944, Parker joined the Billy Eckstine band. The year 1945 proved to be a landmark one for Parker. At this stage in his career, he is believed to have come into his maturity as a musician. For the first time, he became the leader of his own group while also performing with Dizzy Gillespie on the side. At the end of that year, the two musicians launched a six-week nightclub tour of Hollywood. Together they managed to invent an entirely new style of jazz, commonly known as bop, or bebop. After the joint tour, Parker stayed on in Los Angeles, performing until the summer of 1946. After a period of hospitalization, he returned to New York in January of 1947 and formed a quintet there. With his group, Parker performed some of his best-known and best-loved songs, including his own compositions like "Cool Blues." From 1947 to 1951, Parker performed in ensembles and solo at a variety of venues, including clubs and radio stations. Parker also signed with a few different record labels: From 1945 to 1948, he recorded for Dial. In 1948, he recorded for Savoy Records before signing with Mercury. In 1949, Parker made his European debut at the Paris International Jazz Festival and went on to visit Scandinavia in 1950. Meanwhile, back home in New York, the Birdland Club was being named in his honor. In March of 1955, Parker made his last public performance at Birdland, a week before his death. Throughout his adult life, Parker's battles with heroin addiction, alcoholism and mental illness caused turbulence in his career and personal relationships. By the time Parker married Rebecca Ruffin in 1936, he had already started abusing drugs and alcohol. The couple had two children before divorcing in 1939. In 1942, Parker remarried to Geraldine Scott. Financial stresses created a rift between the couple, and Parker turned to heroin for an escape. He ended up leaving his second wife not long after they were married." ^ Hide Bio for Charlie Parker • Show Bio for Miles Davis "Miles Davis, in full Miles Dewey Davis III, (born May 26, 1926, Alton, Illinois, U.S.-died September 28, 1991, Santa Monica, California), American jazz musician, a great trumpeter who as a bandleader and composer was one of the major influences on the art from the late 1940s. Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, where his father was a prosperous dental surgeon. (In later years he often spoke of his comfortable upbringing, sometimes to rebuke critics who assumed that a background of poverty and suffering was common to all great jazz artists.) He began studying trumpet in his early teens; fortuitously, in light of his later stylistic development, his first teacher advised him to play without vibrato. Davis played with jazz bands in the St. Louis area before moving to New York City in 1944 to study at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School)-although he skipped many classes and instead was schooled through jam sessions with masters such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Davis and Parker recorded together often during the years 1945-48. Davis's early playing was sometimes tentative and not always fully in tune, but his unique, intimate tone and his fertile musical imagination outweighed his technical shortcomings. By the early 1950s Davis had turned his limitations into considerable assets. Rather than emulate the busy, wailing style of such bebop pioneers as Gillespie, Davis explored the trumpet's middle register, experimenting with harmonies and rhythms and varying the phrasing of his improvisations. With the occasional exception of multinote flurries, his melodic style was direct and unornamented, based on quarter notes and rich with inflections. The deliberation, pacing, and lyricism in his improvisations are striking. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Miles Davis • Show Bio for Lucky Thompson "Eli "Lucky" Thompson (June 16, 1924 Ð July 30, 2005) was an American jazz tenor and soprano saxophonist whose playing combined elements of swing and bebop. While John Coltrane usually receives the most credit for bringing the soprano saxophone out of obsolescence in the early 1960s, Thompson (along with Steve Lacy) embraced the instrument earlier than Coltrane. Thompson was born in Columbia, South Carolina, and moved to Detroit, Michigan, during his childhood. Thompson had to raise his siblings after his mother died, and he practiced saxophone fingerings on a broom handle before acquiring his first instrument. He joined Erskine Hawkins' band in 1942 upon graduating from high school. After playing with the swing orchestras of Lionel Hampton, Don Redman, Billy Eckstine (alongside Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker), Lucky Millinder, and Count Basie, he worked in rhythm and blues and then established a career in bebop and hard bop, working with Kenny Clarke, Miles Davis, Gillespie and Milt Jackson. Ben Ratliff notes that Thompson "connected the swing era to the more cerebral and complex bebop style. His sophisticated, harmonically abstract approach to the tenor saxophone built off that of Don Byas and Coleman Hawkins; he played with beboppers, but resisted Charlie Parker's pervasive influence." He showed these capabilities as sideman on many albums recorded during the mid-1950s, such as Stan Kenton's Cuban Fire!, and those under his own name. He recorded with Parker (on two Los Angeles Dial Records sessions) and on Miles Davis's hard bop Walkin' session. Thompson recorded albums as leader for ABC Paramount and Prestige and as a sideman on records for Savoy Records with Jackson as leader. Thompson was strongly critical of the music business, later describing promoters, music producers and record companies as "parasites" or "vultures". This, in part, led him to move to Paris, where he lived and made several recordings between 1957 and 1962. During this time, he began playing soprano saxophone. Thompson returned to New York, then lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, from 1968 until 1970, and recorded several albums there including A Lucky Songbook in Europe. He taught at Dartmouth College in 1973 and 1974, then completely left the music business. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Lucky Thompson • Show Bio for Arvin Garrison "Arvin Charles Garrison (August 17, 1922 - July 30, 1960) was an American jazz guitarist. He was born in Toledo, Ohio, and spent most of his life there. Garrison taught himself ukulele at age nine and played guitar for dances and local functions beginning at the age of twelve. He led his own band at a hotel in Albany, New York, in 1941. He married a double bassist and performed with her in a group under her name, the Vivien Garry Trio. They recorded one album. In 1946, Garrison recorded sessions with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie in Los Angeles, sharing the studio with Miles Davis, Dodo Marmarosa, and Lucky Thompson. As part of the Earle Spencer orchestra, he played in a guitar section that included Irving Ashby and Barney Kessel. In the 1950s he returned to Toledo and played locally. In 1960, while he was swimming, he died when he had an epileptic seizure in the water." ^ Hide Bio for Arvin Garrison • Show Bio for Dodo Marmarosa "Michael "Dodo" Marmarosa (December 12, 1925 Ð September 17, 2002) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and arranger. Originating in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Marmarosa became a professional musician in his mid-teens, and toured with several major big bands, including those led by Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, and Artie Shaw into the mid-1940s. He moved to Los Angeles in 1945, where he became increasingly interested and involved in the emerging bebop scene. During his time on the West Coast, he recorded in small groups with leading bebop and swing musicians, including Howard McGhee, Charlie Parker, and Lester Young, as well as leading his own bands. Marmarosa returned to Pittsburgh due to health reasons in 1948. He began performing much less frequently, and had a presence only locally for around a decade. Friends and fellow musicians had commented from an early stage that Marmarosa was an unusual character. His mental stability was probably affected by being beaten into a coma when in his teens, by a short-lived marriage followed by permanent separation from his children, and by a traumatic period in the army. He made comeback recordings in the early 1960s, but soon retreated to Pittsburgh, where he played occasionally into the early 1970s. From then until his death three decades later, he lived with family and in veterans' hospitals." ^ Hide Bio for Dodo Marmarosa • Show Bio for Vic McMillan Vic McMillan was a US bassist known for his work with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie. ^ Hide Bio for Vic McMillan • Show Bio for Roy Porter "Roy Porter accomplished so much in such a short period of time that it is surprising how brief his jazz career actually was. He picked up early experience touring with Milt Larkin in 1943, had a stint in the military and then settled in Los Angeles. Porter worked with Teddy Bunn in 1944, gigged frequently with Howard McGhee (with whom he made his first recordings in 1945) and in 1946 was on a Charlie Parker Dial recording session that resulted in the original versions of "Moose The Mooche," "Yardbird Suite" and "Ornithology." Porter also appeared on Bird's much less successful "Lover Man" date. The drummer was a fixture in Los Angeles' modern jazz scene (particularly on Central Avenue) during those years, recording and gigging with Dexter Gordon, Wardell Gray and Teddy Edwards. He led an experimental big band in 1949 that included among its members Art Farmer, Jimmy Knepper and the young Eric Dolphy; they recorded for Savoy and an apparently long lost date for the tiny Knockout label. The following year Porter relocated to San Francisco but essentially his jazz career was over. Drug problems made the 1950's a barren period, he shifted towards studio work (cutting a few numbers with Earl Bostic), did many commercial and rather anonymous sessions in the 1960's and led two very obscure albums for the tiny Chelan and Bel-Ad labels in 1971 and 1975. Illness forced him to retire altogether by 1978. In 1991 Roy Porter (with the assistance of writer David Keller) came out with his memoirs, There And Back." ^ Hide Bio for Roy Porter • Show Bio for Erroll Garner "Pittsburgh born Jazz pianist, prolific composer, concert hall artist, and recording star. Garner was one of the most well known and influential pianists in the world during his lifetime. Surrounded by a musical family, Garner was by all accounts self-taught, began playing at the age of three and was performing professionally by the age of seven. Throughout his career Garner developed a distinctive and original piano style often compared with Art Tatum, Fats Waller, as well as Claude Debussy. Garner released music on over 40 labels, received multiple Grammy nominations, and recorded one of the greatest selling jazz albums of all time, Concert By The Sea. His published catalog contains nearly 200 compositions including "Misty", which was named #15 on ASCAP's list of the top songs of the 20th century. He scored for ballet, film, television, and orchestra. One of the most televised Jazz artists of his era, Garner appeared on TV shows all over the world, including: Ed Sullivan, Dick Cavitt, Steve Allen, Johnny Carson, and many others. His prolific career began on Allegheny riverboats and spanned from the clubs of 52nd street to the top concert halls of the world. Erroll Garner's musical and cultural legacy is perhaps stronger today than at any point since his untimely passing in 1977, when Erroll lost his battle with lung cancer at the age of 55. Thanks to the renewed efforts of Octave Music-the successor and namesake of the company Garner formed with his manager Martha Glaser in 1952- and it's Erroll Garner Jazz Project, his music is once again finding fresh audiences through a series of new record releases, multimedia performances, and creative partnerships." ^ Hide Bio for Erroll Garner • Show Bio for Red Callender "George Sylvester "Red" Callender (March 6, 1916 Ð March 8, 1992) was an American string bass and tuba player. He is perhaps best known as a jazz musician, but worked with an array of pop, rock and vocal acts as a member of The Wrecking Crew, a group of first-call session musicians in Los Angeles. Callender was born in Haynesville, Virginia. In the early 1940s, he played in the Lester and Lee Young band, and then formed his own trio. In the 1940s Callender recorded with Nat King Cole, Erroll Garner, Charlie Parker, Wardell Gray, Dexter Gordon, Uffe Baadh [Frank Bode] and many others. After a period spent leading a trio in Hawaii, Callender returned to Los Angeles, becoming one of the first black musicians to work regularly in the commercial studios, including backing singer Linda Hayes on two singles. He made his recording debut at 19 with Louis Armstrong's band. However, he later turned down offers to work with Duke Ellington's Orchestra and the Louis Armstrong All-Stars. On his 1957 Crown LP Speaks Low, Callender was one of the earliest modern jazz tuba soloists. Keeping busy up until his death, some of the highlights of the bassist's later career include recording with Art Tatum and Jo Jones (1955Ð1956) for the Tatum Group, playing with Charles Mingus at the 1964 Monterey Jazz Festival, working with James Newton's avant-garde woodwind quintet (on tuba), and performing as a regular member of the Cheatham's Sweet Baby Blues Band. He also reached the top of the British pop charts as a member of B. Bumble and the Stingers. In November 1964 he was introduced and highlighted in performance with entertainer Danny Kaye in a duet on the Fred Astaire introduced George and Ira Gershwin song, Slap That Bass, for Kaye's CBS-TV variety show. Callender died of thyroid cancer at his home in Saugus, California." ^ Hide Bio for Red Callender • Show Bio for Doc West "If he had been a "Doc" of the Old West, then perhaps Doc West would have become a household name, of the stature of a Doc Holliday or similar Western gunslinger. Yet even amongst the crowd of bebop fanatics, and certainly in the annals of jazz history, the drummer who also has many credits under his real name of Harold West, tends to be overshadowed by slightly later bebop drum stylists; Max Roach, for instance. Emerging from the hinterlands of North Dakota, the versatile West had already learned to play both the piano and cello before changing to drums. Having in a sense an intellectual command of the entire rhythm section, he was several steps above the porch where the normal jazz drummer of his era was sitting. No doubt his fame would have been greater in jazz had he survived past the early '50s. His career began roughly two decades prior in the band of Tiny Parham in Chicago. Soon he was also swinging behind the lovely trumpet solos of Roy Eldridge, as well as playing in a combo led by the somewhat more traditional Erskine Tate. From there he became part of an elite class of jazz stand-ins, in this case filling in the gaps for Chick Webb when that popular bandleader and drummer was touring Texas in the late '30s. He finished out that decade and got a bit into the '40s burned by the flame of Hot Lips Page, in whose band he found the navigational compass to the New York scene as well as displaying the difficult art of swinging a band hard while still playing quite quietly. This would become a crux point in emerging bebop drum styles, as the harmonic artistry and elaborate melodic oratorio of the lead soloists was not to be drowned out, although interrupting with a well-placed bass bomb was absolutely no problem. West played in many a jam at the famed Minton's Playhouse venue in the Big Apple, while simultaneously laying down a more fundamental groove when subbing for roots jazz maestro Jo Jones in the big band of Count Basie. In 1945, the man had established beyond a doubt that he could handle either the swing or bop styles, and was getting calls for gigs and recording sessions in both styles. He shows up on some of the most sheerly entertaining music of this era. While bebop is unfairly categorized as being overly analytical, the recordings of Slam Stewart, Leo Watson, and Wardell Gray ranged from profoundly moving to profoundly amusing, the pulse of the drums always a life force. Since it is bebop history, the trail leads to Charlie Parker, and jazz Mounties would have to agree that West's main claim to fame would be the sessions he was involved with featuring that great saxophonist as well as the fine guitarist Tiny Grimes; with a "Tiny," a "Bird," and a "Doc" in the gang, this might as well have been a meeting of Western gunslingers. This is some of the most popular material by Parker, whose recordings are sometimes released according to historical timetables by competing jazz record companies, most of whom try to stretch the dates in order to include these sessions. Many listeners most likely have heard the drummer in the company of the great vocalist Billie Holiday, including the haunting Strange Fruit. Erroll Garner is another superb player whose discography includes a great deal of this drummer's work, as he held down the seat in that pianist's first important trio from the mid-'40s onward. West continued collaborating with Eldridge as well; in fact, the drummer died while on the road with Eldridge's band."-Eugene Chadbourne ^ Hide Bio for Doc West • Show Bio for Howard McGhee "During 1945-1949, Howard McGhee was one of the finest trumpeters in jazz, an exciting performer with a sound of his own, who among the young bop players, ranked at the top with Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Navarro. The "missing link" between Roy Eldridge and Fats Navarro (Navarro influenced Clifford Brown who influenced most of the post-1955 trumpeters), McGhee originally played clarinet and tenor, not taking up trumpet until he was 17. He worked in territory bands, was with Lionel Hampton in 1941, and then joined Andy Kirk (1941-1942), being featured on "McGhee Special." McGhee participated in the fabled bop sessions at Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House, modernizing his style away from Roy Eldridge and towards Dizzy Gillespie. He was with Charlie Barnet (1942-1943), returned to Kirk (where he sat next to Fats Navarro in the trumpet section), and had brief stints with Georgie Auld and Count Basie before traveling to California with Coleman Hawkins in 1945; their concise recordings of swing-to-bop transitional music (including "Stuffy," "Rifftide," and "Hollywood Stampede") are classic. McGhee stayed in California into 1947, playing with Jazz at the Philharmonic, recording and gigging with Charlie Parker (including the ill-fated "Lover Man" date) and having an influence on young players out on the Coast. His Dial sessions were among the most exciting recordings of his career, and back in New York he recorded for Savoy and had a historic meeting on record with Navarro in 1948 on Blue Note. Eventually, drugs began to affect McGhee's career. He traveled on a USO tour during the Korean War, recording in Guam. McGhee also had sessions for Bethlehem (1955-1956) but was inactive during much of the '50s. He recorded some strong dates for Felsted, Bethlehem, Contemporary, and Black Lion during 1960-1961, and on a quartet outing for United Artists (1962), but (with the exception of a Hep big band date in 1966) was largely off records again until 1976. He had a final burst of activity during 1976-1979 for Sonet, SteepleChase, Jazzcraft, Zim, and Storyville, but by then, McGhee was largely forgotten and few knew about his link to Fats Navarro and Clifford Brown." ^ Hide Bio for Howard McGhee • Show Bio for Wardell Gray "Carl Wardell Gray was born on February 13, 1921 in Oklahoma City, the youngest of four children, to Eugene, from Georgia, and Carrie Gray (nee Maddison), from Alabama. His early childhood years were spent in Oklahoma, but the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, in 1929 as part of the great black migration to the urban centers of the northern states that promised greater economic opportunities and personal freedoms. Unfortunately, the family arrived just in time for the great depression, so no doubt the family faced some hard economic times. Census records indicate that in 1930 the Gray family was lodging at the home of James Chager on 505 E. Kirby Street in Detroit. Wardell, age 9, and older brother Harry, age 11, are the only Gray children listed as living at that address. Sisters Madeline, the oldest, and Edith are not mentioned in the census records. In early 1935, Gray began attending Northeastern High School, and then transferred to the well known Cass Technical High School in downtown Detroit, which is noted for having Donald Byrd, Lucky Thompson, Howard McGhee, Gerald Wilson and Al McKibbon as alumni. Advised by his brother-in-law Junior Warren, as a teenager he started on the clarinet, but after hearing Lester Young on record with Count Basie, he was inspired to switch to the tenor saxophone. It has also been reported that brother Harry, who played bass, encouraged his interest in music. Gray's first musical job was in Isaac Goodwin's small band, a part-time outfit that played local dances. When auditioning for another job, he was heard by Dorothy Patton, a young pianist who was forming a band at the Fraternal Club in Flint, Michigan, and she hired him. After a very happy year there, he moved to Jimmy Raschel's band. (Raschel had recorded a few sides earlier in the 1930s and is the father of Jimmy Raschel, the contemporary country western singer.) He then joined the Benny Carew band in Grand Rapids, Michigan. It was around this time that he met Jeanne Goings. They were soon married and had a daughter, Anita, who was born in January, 1941. Anita L. Gray-McClelland is still living and currently resides in Lansing, Michigan. A neighbor and friend, Patti Richards, speaks of Gray as already a wonderful musician who was fully aware of his gifts. She describes Gray as highly intelligent, good natured and friendly, and with a good but sometimes sarcastic sense of humor. He was very much aware of the barriers that his race would likely to play in his career. By then Wardell had reached the height of 6 feet 4 inches and was very thin despite having a healthy appetite. Years later trumpet great Clark Terry would jokingly refer to him as "Bones." [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Wardell Gray • Show Bio for Duke Jordan "Although he had a long career, Duke Jordan will always be best known for being pianist with Charlie Parker's classic 1947 quintet. A little earlier, he worked with the Savoy Sultans, Coleman Hawkins, and the Roy Eldridge big band (1946). After his year with Parker (his piano introductions to such songs as "Embraceable You" were classic), Jordan worked with the Sonny Stitt/Gene Ammons quintet (1950-1951) and Stan Getz (1949 and 1952-1953). He started recording as a leader in 1954, debuting his most famous composition, "Jor-Du," the following year. Although he worked steadily during the next few decades (writing part of the soundtrack for the French film Les Liaisons Dangereuses), Jordan was in obscurity until he began recording on a regular basis for Steeplechase in 1973. Duke Jordan, who was married for a time to the talented jazz singer Sheila Jordan, lived in Denmark from 1978 until his death on August 8, 2006. He recorded through the years for Prestige, Savoy, Blue Note, Charlie Parker Records, Muse, Spotlite, and Steeplechase."-Scott Yanow ^ Hide Bio for Duke Jordan • Show Bio for Tommy Potter "Charles Thomas Potter (September 21, 1918 - March 1, 1988) was a jazz double bass player, best known for having been a member of Charlie Parker's "classic quintet", with Miles Davis, between 1947 and 1950. Born in Philadelphia, Potter had first played with Parker in 1944, in Billy Eckstine's band with Dizzy Gillespie, Lucky Thompson and Art Blakey. Potter also performed and recorded with many other notable jazz musicians, including Earl Hines, Artie Shaw, Bud Powell, Count Basie, Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz, Max Roach, Eddie Heywood, Tyree Glenn, Harry "Sweets" Edison, Buck Clayton and Charles Lloyd." ^ Hide Bio for Tommy Potter • Show Bio for Max Roach "Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 - August 16, 2007) was an American jazz drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in history. He worked with many famous jazz musicians, including Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Abbey Lincoln, Dinah Washington, Charles Mingus, Billy Eckstine, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, and Booker Little. He was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1992. Roach also co-led a pioneering quintet along with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the percussion ensemble M'Boom. He made numerous musical statements relating to the civil rights movement. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Max Roach • Show Bio for J.J. Johnson "James Louis Johnson (January 22, 1924 Ð February 4, 2001) was an American jazz trombonist, composer and arranger. Johnson was one of the earliest trombonists to embrace bebop. After studying the piano beginning at age 9, Johnson decided to play trombone at the age of 14. In 1941, he began his professional career with Clarence Love, and then played with Snookum Russell in 1942. In Russell's band he met the trumpeter Fats Navarro, who influenced him to play in the style of the tenor saxophonist Lester Young. Johnson played in Benny Carter's orchestra between 1942 and 1945, and made his first recordings in 1943 under Carter's leadership, recording his first solo (on Love for Sale) in October 1943. In 1944, he took part in the first Jazz at the Philharmonic concert, presented in Los Angeles and organized by Norman Granz. In 1945 he joined the big band of Count Basie, touring and recording with him until 1946. While the trombone was featured prominently in dixieland and swing music, it fell out of favor among bebop musicians, largely because instruments with valves and keys (trumpet, saxophone) were believed to be more suited to bebop's often rapid tempos and demand for technical mastery. In 1946, bebop co-inventor Dizzy Gillespie encouraged the young trombonist's development with the comment, "I've always known that the trombone could be played different, that somebody'd catch on one of these days. Man, you're elected." After leaving Basie in 1946 to play in small bebop bands in New York clubs, Johnson toured in 1947 with Illinois Jacquet. During this period he also began recording as a leader of small groups featuring Max Roach, Sonny Stitt and Bud Powell. He performed with Charlie Parker at the 17 December 1947 Dial Records session following Parker's release from Camarillo State Mental Hospital. In 1951, with bassist Oscar Pettiford and trumpeter Howard McGhee, Johnson toured the military camps of Japan and Korea before returning to the United States and taking a day job as a blueprint inspector. Johnson admitted later he was still thinking of nothing but music during that time, and indeed, his classic Blue Note Records recordings as both a leader and with Miles Davis date from this period. Johnson's compositions "Enigma" and "Kelo" were recorded by Davis for Blue Note and Johnson was part of the Davis studio session band that recorded the jazz classic Walkin' (1954). [...]" ^ Hide Bio for J.J. Johnson

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Moose The Mooche 3:06

2. Yardbird Suite 2:56

3. Ornithology 3:02

4. A Night In Tunisia 3:06

5. Bird's Nest 2:46

6. Cool Blues 3:07

7. Relaxin' At Camarillo 3:03

8. Dexterity 2:59

9. Bongo Bop 2:28

10. Dewey Square 3:07

11. The Hymn 2:29

12. Bird Of Paradise 3:12

13. Embraceable You 3:22

14. Bird Feathers 2:51

15. Klact-oveeseds-tene 2:51

16. Scrapple From The Apple 2:57

17. My Old Flame 3:11

18. Out Of Nowhere 3:51

19. Don't Blame Me 2:47

20. Drifting On A Reed 3:02

21. Quasimado 2:59

22. Charlie's Wig 2:47

23. Bongo Beep 3:05

24. Crazeology 3:03

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

West Coast/Pacific US Jazz

Quartet Recordings

Quintet Recordings

Sextet Recordings

Septet recordings

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Top Sellers for 2020 by Customer Sales

Jazz & Improvisation Based on Compositions

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![BlueRing Improvisers: Materia [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36513.jpg)

![Wheelhouse (Rempis / Adasiewicz / McBride): House And Home [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36462.jpg)

![+DOG+: The Light Of Our Lives [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36009.jpg)

![Parker, Evan / Jean-Marc Foussat: Insolence [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36398.jpg)

![Deupree, Jerome / Sylvie Courvoisier / Lester St. Louis / Joe Morris: Canyon [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36404.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)