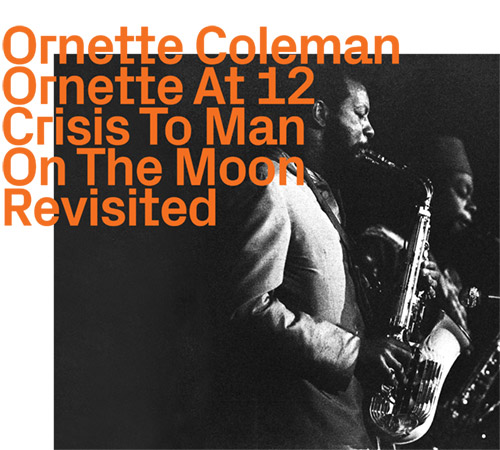

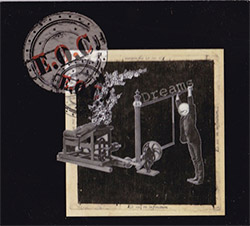

Reissuing and remastering two Impulse! albums from saxophonist Ornette Coleman: 1969's Ornette At 12 with Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden and his then 12-year-old son Denardo on drums; 1972's Crisis adding Don Cherry on trumpet; and a lesser-known 1969 EP, Man On The Moon, with electronics from Dr. Emmanuel Ghent and Ed Blackwell on drums.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Ornette Coleman-alto saxophone, violin, trumpet

Dewey Redman-tenor saxophone, clarinet

Charlie Haden-double bass

Denardo Coleman-drums

Don Cherry-trumpet, flute

Ed Blackwell-drums

Dr Emmanuel Ghent-electronics

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156114826

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1148

Squidco Product Code: 33072

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2023

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Tracks 1-4 recorded live at Heart Greek Amphitheater, at the University of California, Berkley on August 11th, 1968.

Tracks 5-9 recorded live at New york University, in NYC, on March 22n, 1969.

Tracks 10 and 11 recorded at O'Brien studio, in New Jersey, on June 7th, 1969.

Man On The Moon / Growing Up was originally released in 1969 as a 7" promotional record on the Impulse! label with catalog code 45-275.

Ornette at 12 was originally released in 1969 as a vinyl LP on the Impulse! label with catalog code AS-9178.

Crisis was originally released in 1972 as a vinyl LP on the Impulse! label with catalog code AS-9187.

"It's an interesting and rather curious phenomenon how many of the leading "progressive" jazz artists of the 1960s were conspicuously absent from recording studios for years at a time towards the end of the decade and into the next, variously including Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, Charles Mingus, George Russell, Sam Rivers, Cecil Taylor, and Ornette Coleman among others. Representing a lack of major label commitment during a declining and changing marketplace (particularly due to the popularity of countercultural rock music), less expensive concert and nightclub recordings were necessary to maintain their public awareness. Even so, live performances were not always a viable solution.

More than a few jazz musicians found Europe to be a financial and creative alternative to America during this time; while Rollins, Taylor, and Ornette in particular chose to distance themselves from performance venues for reasons of personal dissatisfaction, unrealistically low compensation, and racial disrespect. In Ornette's case, the first such hiatus took place between 1962 and '65, after his initial breakthrough on the New York scene had dissipated, and he rejected the necessity of hustling for gigs that paid less than he felt he deserved. In late-1965 and early-'66 he accepted Scandinavian and European tours in a trio setting with bassist David Izenzon and drummer Charles Moffett, and back in the U.S. in September, entered a studio for the first time since 1961 (with the exception of his work on the unused film score for Chappaqua), this time accompanied by bassist Charlie Haden and the ten-year-old son of Ornette and poet Jayne Cortez, Denardo, on drums, for the album The Empty Foxhole.

Denardo's age and unconventional playing sparked a controversy, which Ornette countered by saying "I felt the joy playing with someone who hasn't had to care if the music business or musicians or critics would help or destroy his desire to express himself honestly." According to Ornette's creative philosophy, in a truly free improvisational music a sincere expression of intent and an unburdened sense of spirit were more important than instrumental technique or traditional musical values. Who better to be free of the clichés of the past than someone who never learned them? This same point of view explains his own self-taught adoption of the violin and trumpet.

During the late '60s Ornette's live performances continued to be sporadic, and it would be another two years before Blue Note brought him back into a recording studio as a leader [New York Is Now & Love Call Revisited, ezz-thetics 1125], this time including saxophonist Dewey Redman and, temporarily, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones as rhythm section - an ironic counterpoint to John Coltrane using Ornette's rhythm section and trumpeter Don Cherry eight years earlier for The Avant-Garde (although Ornette did not fully return the favor by recording any of Coltrane's tunes). Redman, meanwhile, was to remain a surprising and valuable addition to Ornette's occasional combo (it would be inaccurate to call it a "working" group) until the mid-70s emergence of Prime Time. However, notwithstanding Denardo's debut in 1966, in Ornette's rare appearances either in New York or overseas from 1968 to the mid-'70s, longtime colleague Ed Blackwell filled the drum chair, with two notable exceptions - the two live concert recordings contained herein, Ornette at 12 and Crisis.

The title Ornette at 12 is something of a misnomer. Although Ornette is Denardo's middle name, why wasn't the album called "Denardo at 12", his age at the time of the concert? Is there a hidden meaning related to Ornette's own childhood? According to John Litweiler's book A Harmolodic Life, he was either 13 or 14 when he received his first horn. If the year 1956 is meant to represent a significant event in Ornette's musical life, it does mark his meeting with Don Cherry and Billy Higgins, and their first rehearsals and gigs together in Los Angeles. But neither were part of this concert. The title remains a mystery.

Nevertheless, the music from these two concerts, separated by seven months, is remarkable. Without subjecting his drumming to conventional jazz standards - which in this music is beside the point - Denardo's contribution is altogether appropriate and often compelling, revealing alert dynamics, altered textures, sensitive and energetic support. Redman's blues-infused commentaries on Ornette's themes are a dramatic contrast to Ornette's characteristic cry and circuitous, albeit lyrical, logic. The compositions - yearning ballad or soaring pyrotechnics - are memorable. As a bonus encore, ezz-thetics has attached the music from the little-known 45-rpm single that Ornette released in 1969 to celebrate the first moon landing. Unique to "Man on the Moon" is the electronic component by Emmanuel Ghent, a pathbreaking psychologist and early practitioner of computer-generated electronic music, who for a time lived in the same building as Ornette and according to his son jammed informally with him frequently.

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Ornette Coleman "Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman (March 9, 1930 - June 11, 2015) was an American jazz saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter, and composer known as a principal founder of the free jazz genre, a term derived from his 1960 album Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation. His pioneering performances often abandoned the chordal and harmony-based structure found in bebop, instead emphasizing a jarring and avant-garde approach to improvisation. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, Coleman began his musical career playing in local R&B and bebop groups, and eventually formed his own group in Los Angeles featuring members such as Ed Blackwell, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, and Billy Higgins. In 1959, he released the controversial album The Shape of Jazz to Come and began a long residency at the Five Spot jazz club in New York City. His 1960 album Free Jazz would profoundly influence the direction of jazz in that decade. Beginning in the mid-1970s, Coleman formed the group Prime Time and explored funk and his concept of Harmolodic music. Coleman's "Broadway Blues" and "Lonely Woman" became genre standards and are cited as important early works in free jazz. His album Sound Grammar received the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Music. AllMusic called him "one of the most important (and controversial) innovators of the jazz avant-garde"." ^ Hide Bio for Ornette Coleman • Show Bio for Dewey Redman "Walter Dewey Redman (May 17, 1931 - September 2, 2006) was an American saxophonist who performed free jazz as a bandleader and with Ornette Coleman and Keith Jarrett. Redman mainly played tenor saxophone, though he occasionally also played alto, the Chinese suona (which he called a musette), and clarinet. His son is saxophonist Joshua Redman." ^ Hide Bio for Dewey Redman • Show Bio for Charlie Haden "Charles Edward Haden (August 6, 1937 - July 11, 2014) was an American jazz double bass player, bandleader, composer and educator whose career spanned more than 50 years. In the late 1950s, he was an original member of the ground-breaking Ornette Coleman Quartet. Haden revolutionized the harmonic concept of bass playing in jazz. German musicologist Joachim-Ernst Berendt wrote that Haden's "ability to create serendipitous harmonies by improvising melodic responses to Coleman's free-form solos (rather than sticking to predetermined harmonies) was both radical and mesmerizing. His virtuosity lies (...) in an incredible ability to make the double bass 'sound out'. Haden cultivated the instrument's gravity as no one else in jazz. He is a master of simplicity which is one of the most difficult things to achieve." Haden played a vital role in this revolutionary new approach, evolving a way of playing that sometimes complemented the soloist and sometimes moved independently. In this respect, as did his predecessor bassists Jimmy Blanton and Charles Mingus, Haden helped liberate the bassist from a strictly accompanying role to becoming a more direct participant in group improvisation. In 1969, he formed his first band, the Liberation Music Orchestra, featuring arrangements by pianist Carla Bley. In the late 1960s, he became a member of pianist Keith Jarrett's trio, quartet and quintet. In the 1980s, he formed his band, Quartet West. Haden also often recorded and performed in a duo setting, with musicians including guitarist Pat Metheny and pianist Hank Jones." ^ Hide Bio for Charlie Haden • Show Bio for Denardo Coleman "Denardo Ornette Coleman (born April 19, 1956) is an American jazz drummer. He is the son of Ornette Coleman and Jayne Cortez.Biography Born to Jayne Cortez and Ornette Coleman in Los Angeles, California, in 1956, Denardo Coleman began playing drums at the age of six. At the age of 10 he joined his father's band, making his first appearance on record on the 1966 Ornette Coleman album The Empty Foxhole, with Charlie Haden on bass. Haden said of Denardo's playing on that recording: "He's going to startle every drummer who hears him." Denardo also featured on his father's later releases, including Ornette at 12 (1968) and Crisis (1969), and played as a member of Ornette's Prime Time ensemble in the 1970s. He also worked with his mother in the band The Firespitters, and has played with Geri Allen, Pat Metheny, James Blood Ulmer, and Jamaaladeen Tacuma. In the 1980s Coleman started to manage his father's career, which he continued doing for the next 30 years. Coleman has also done extensive work as a producer, including on albums by both of his parents, and on In All Languages and Virgin Beauty in the 1980s and Hidden Man and Three Women in the '90s. In 2017, on a new label called Song X Records (referencing the title of one of his father's favorite compositions), he produced Celebrate Ornette, a tribute to his father, in a box set with 24 performances captured on two DVDs, three CDs, and four vinyl LPs." ^ Hide Bio for Denardo Coleman • Show Bio for Don Cherry "Imagination and a passion for exploration made Don Cherry one of the most influential jazz musicians of the late 20th century. A founding member of Ornette Coleman's groundbreaking quartet of the late '50s, Cherry continued to expand his musical vocabulary until his death in 1995. In addition to performing and recording with his own bands, Cherry worked with such top-ranked jazz musicians as Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and Gato Barbieri. Cherry's most prolific period came in the late '70s and early '80s when he joined Nana Vasconcelos and Collin Walcott in the worldbeat group Codona, and with former bandmates Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell, and saxophonist Dewey Redman in the Coleman-inspired group Old and New Dreams. Cherry later worked with Vasconcelos and saxophonist Carlos Ward in the short-lived group Nu. The Avant-Garde Born in Oklahoma City in 1936, he first attained prominence with Coleman, with whom he began playing around 1957. At that time Cherry's instrument of choice was a pocket trumpet (or cornet) -- a miniature version of the full-sized model. The smaller instrument -- in Cherry's hands, at least -- got a smaller, slightly more nasal sound than is typical of the larger horn. Though he would play a regular cornet off and on throughout his career, Cherry remained most closely identified with the pocket instrument. Cherry stayed with Coleman through the early '60s, playing on the first seven (and most influential) of the saxophonist's albums. In 1960, he recorded The Avant-Garde with John Coltrane. After leaving Coleman's band, Cherry played with Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, and Albert Ayler. In 1963-1964, Cherry co-led the New York Contemporary Five with Shepp and John Tchicai. With Gato Barbieri, Cherry led a band in Europe from 1964-1966, recording two of his most highly regarded albums, Complete Communion and Symphony for Improvisers. Cherry began the '70s by teaching at Dartmouth College in 1970, and recorded with the Jazz Composer's Orchestra in 1973. He lived in Sweden for four years, and used the country as a base for his travels around Europe and the Middle East. Cherry became increasingly interested in other, mostly non-Western styles of music. In the late '70s and early '80s, he performed and recorded with Codona, a cooperative group with percussionist Nana Vasconcelos and multi-instrumentalist Collin Walcott. Codona's sound was a pastiche of African, Asian, and other indigenous musics. Art Deco Concurrently, Cherry joined with ex-Coleman associates Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell, and Dewey Redman to form Old and New Dreams, a band dedicated to playing the compositions of their former employer. After the dissolution of Codona, Cherry formed Nu with Vasconcelos and saxophonist Carlos Ward. In 1988, he made Art Deco, a more traditional album of acoustic jazz, with Haden, Billy Higgins, and saxophonist James Clay. Multikulti Until his death in 1995, Cherry continued to combine disparate musical genres; his interest in world music never abated. Cherry learned to play and compose for wood flutes, tambura, gamelan, and various other non-Western instruments. Elements of these musics inevitably found their way into his later compositions and performances, as on 1990's Multi Kulti, a characteristic celebration of musical diversity. As a live performer, Cherry was notoriously uneven. It was not unheard of for him to arrive very late for gigs, and his technique -- never great to begin with -- showed on occasion a considerable, perhaps inexcusable, decline. In his last years, especially, Cherry seemed less self-possessed as a musician. Yet his musical legacy is one of such influence that his personal failings fade in relative significance." ^ Hide Bio for Don Cherry • Show Bio for Ed Blackwell "Edward Joseph Blackwell (October 10, 1929 - October 7, 1992) was an American jazz drummer born in New Orleans, Louisiana, known for his extensive, influential work with Ornette Coleman. Blackwell's early career began in New Orleans in the 1950s. He played in a bebop quintet that included pianist Ellis Marsalis and clarinetist Alvin Batiste. There was also a brief stint touring with Ray Charles. The second line parade music of New Orleans greatly influenced Blackwell's drumming style and could be heard in his playing throughout his career. Blackwell first came to national attention as the drummer with Ornette Coleman's quartet around 1960, when he took over for Billy Higgins in the quartet's stand at the Five Spot in New York City. He is known as one of the great innovators of the free jazz of the 1960s, fusing New Orleans and African rhythms with bebop. In the 1970s and 1980s Blackwell toured and recorded extensively with fellow Ornette Quartet veterans Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, and Dewey Redman in the quartet Old and New Dreams. In the late 1970s Blackwell became an Artist-in-Residence at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. Blackwell was a beloved figure on the Wesleyan Campus until he died. In 1981, he performed at the Woodstock Jazz Festival, held in celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Creative Music Studio. "The Ed Blackwell Project" members were Mark Helias, bass, Carlos Ward, alto sax/flute, and Graham Haynes (son of drummer Roy Haynes), cornet. After years of kidney problems, Blackwell died in 1992. The following year he was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame." ^ Hide Bio for Ed Blackwell • Show Bio for Dr Emmanuel Ghent "Emmanuel Robert Ghent (May 15, 1925 in Montréal, Quebec - March 31, 2003 in New York City, USA) was a pioneering composer of electronic music and a psychiatric practitioner, researcher, and teacher. Emmanuel Ghent was born in Montreal, Quebec. He grew up in Montreal and attended McGill University to study medicine. After graduating, he moved to New York City to continue his psychiatric training. He remained there all his life, practicing in New York and eventually becoming a clinical professor of psychology at the postdoctoral program in psychoanalysis at New York University. Throughout his life, Ghent worked to expand his field of psychoanalysis beyond psychiatric practitioners. [...] Music ^ Hide Bio for Dr Emmanuel Ghent

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Ghent was also an amateur oboist and composer of electronic music. In the 1960s, Ghent pioneered the concept of electronic music by adapting a computer system, initially designed to synthesize the human voice, to instead synthesize music. With the advent of more sophisticated computer systems in the 1970s, Ghent was able to synchronize the lighting of the theater with the synthesized music. Ghent could thus create music that combined music, dance and light patterns. In fact, several of his most famous compositions used this idea, most notably "Phosphones" and "Five Brass Voices for Computer-Generated Tape." Ghent wrote non-electronic music too, including "Entelechy for Viola and Piano" and "25 Songs for Children and All Their Friends" (written to commemorate the birth of Ghent's third daughter, Theresa Ghent Locklear)."

7/1/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. C.O.D. 7:29

2. Rainbows 8:59

3. New York 8:16

4. Bells And Chimes 7:13

5. Broken Shadows 6:08

6. Comme II Faut 13:54

7. Song For Che 10:30

8. Space Jungle 5:21

9. Trouble In the East 6:41

10. Man On The Moon 3:10

11. Growing Up 2:16

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Free Improvisation

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Quartet Recordings

Quintet Recordings

Sextet Recordings

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

New in Improvised Music

Top Sellers for 2023 by Customer Sales

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![Deupree, Jerome / Sylvie Courvoisier / Lester St. Louis / Joe Morris: Canyon [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36404.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Hemphill Stringtet, The: Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36409.jpg)

![Halvorson, Mary Septet: Illusionary Sea [2 LPS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17952.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Nakayama, Tetsuya: Edo Wan [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36105.jpg)

![Yiyuan, Liang / Li Daiguo: Sonic Talismans [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35957.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)