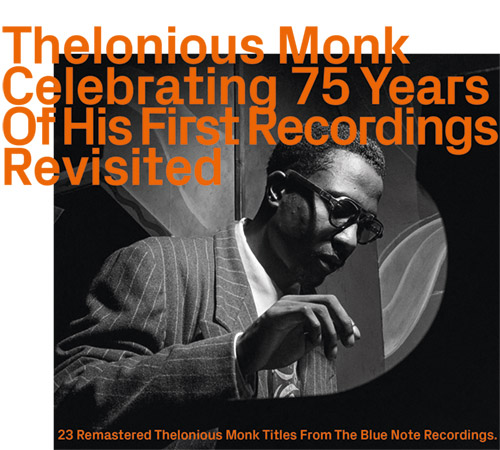

The foundational work of composer and pianist Thelonious Monk is heard in these six remastered studio sessions for Blue Note Records recorded between 1947 to 1952, performing twenty three original compositions in bands from trios to sextets with a who's who of emerging jazz leaders including Art Blakey, Max Roach, Lou Donaldson, Kenny Dorham, and Milt Jackson.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Thelonious Monk-piano

Idrees Sulieman-trumpet

Danny Quebec West-alto saxophone

Billy Smith-tenor saxophone

Gene Ramey-bass

Art Blakey-drums

George Taitt-trumpet

Sahib Shihab-alto saxophone

Robert Paige-bass

Milt Jackson-vibes

John Simmons-bass

Shadow Wilson-drums

Al McKibbon-bass

Kenny Dorham-trumpet

Lou Donaldson-alto saxophone

Lucky Thompson-tenor saxophone

Nelson Boyd-bass

Max Roach-drums

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156114123

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1141

Squidco Product Code: 32495

Format: CD

Condition: Sale (New)

Released: 2022

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

The Thelonious Monk Sextet

Idrees Sulieman,trumpet; Danny Quebec West,alto saxophone; Billy Smith, tenor saxophone; Thelonious Monk, piano; Gene Ramey, bass; Art Blakey, drums at WOR Studios, NYC, October 15, 1947 recording the compositions 1 Thelonious & 9 Humph.

The Thelonious Monk Trio

Thelonious Monk, piano; Gene Ramey, bass; Art Blakey, drums at WOR Studios, NYC, October 24, 1947 recording the compositions 3 Well You Needn't, 4 Off Minor, 7 Ruby My Dear & 22 Introspection.

The Thelonious Monk Quintet

George Taitt, trumpet; Sahib Shihab, alto saxophone; Thelonious Monk, piano; Robert Paige, bass; Art Blakey, drums at WOR Studios, NYC, November 21, 1947 recording the compositions 2 'Round Midnight, 5 In Walked Bud, 12 Monk's Mood & 13 Who Knows.

The Thelonious Monk Quartet

Milt Jackson, vibes; Thelonious Monk, piano; John Simmons, bass; Shadow Wilson, drums at Apex Studios, NYC, July 2, 1948 recording the compositions 6 Epistrophy, 8 Evidence, 10 Misterioso & 11 I Mean You.

The Thelonious Monk Quintet

Sahib Shihab, alto saxophone on *; Milt Jackson, vibes on *; Thelonious Monk, piano; Al McKibbon, bass; Art Blakey, drums at WOR Studios, NYC, July 23, 1951 recording the compositions 14 Four In One*, 15 Straight No Chaser*, 16 Criss-Cross*, 17 Eronel*, & 18 Ask Me Now.

The Thelonious Monk Sextet

Kenny Dorham, trumpet; Lou Donaldson, alto saxophone; Lucky Thompson, tenor saxophone; Thelonious Monk, piano; Nelson Boyd, bass; Max Roach, drums at WOR Studios, NYC, May 30, 1952 recording the compositions 19 Skippy, 20 Let's Cool One, 21Hornin'In &23Sixteen.

"He has written a few attractive tunes, but his lack of technique and continuity prevents him from accomplishing much as a pianist."

The fatal flaw in Leonard Feather's 1949 assessment of Thelonious Monk (from the book Inside Bebop) was a then relatively common, albeit insidiously superficial and short-sighted, perspective: jazz as an interpretive, and not a fully integrated compositional, discipline. From this point-of-view, the improvisational skills of a jazz musician were seen as a way to exploit, and at best enhance, the familiar aspects of popular song form, while simultaneously displaying their digital virtuosity. At this point in time, the avatar of piano technique put to the use of flamboyant ornamentation was Art Tatum; other notable figures, like Earl Hines and Teddy Wilson, brought melodic ingenuity and elegance to their performances. Even the emerging Bud Powell could be rationalized as a boppish reconfiguration of Tatum's keyboard prowess.

But instrumentalists of even their stature did not compose the bulk of their repertoire. And those few pianists who had established an early reputation in jazz composition - primarily Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington (or, slightly later, a Tadd Dameron or George Russell) - were misunderstood to be players within a functional, if not intentionally crowd-pleasing, role. (We can argue Morton's exceptions to this description at some later date.) On his own, however, Monk devised a new theoretical basis for his compositional aesthetic, an unorthodox, deconstructed and reinvented pianistic approach that defined his music's unique rhythmic and melodic parameters. Simply put, by 1949 (and thereafter) his idiosyncratic piano technique and his radical compositions were cut from the same cloth, fully integrated as to form and function. The piano was the vehicle of expression for his compositional mindset, which explains his various surgical confrontations with "standards," which he was not interpreting but re-composing from the inside-out, and the resulting misconception of his "lack of technique and continuity."

The evidence is here, on this disc, which collects the twenty-three original pieces he recorded in the six studio sessions for Blue Note from 1947 to 1952. It's especially revealing that so many of these remarkably creative pieces - far from being the merely "attractive tunes" that Feather scarcely acknowledged - came to comprise the foundation of Monk's canon, revisited often throughout his performing career, suggesting that the composer selected them specifically to elaborate new variation upon variation, spontaneously, of their rhythmic and harmonic eccentricities, very much as J.S. Bach did two centuries earlier.

In fact, the majority of these compositions are probably better known in other, later, frequently live, versions than these first releases, which nevertheless allows us the opportunity to re-experience the jolting effect of their initial impulse. As Gunther Schuller has suggested, at their best they are no longer "tunes" but tone poems; drama and design are indivisible. Monk's complex, intrinsic sense of detail and construction take precedence over instrumental application. In the widely spread intervals and cascades throughout "Ruby My Dear" or the insistent chords and repeated notes of "Well You Needn't" the choices seem more ear-oriented than pianistically practical. Likewise, the asymmetrical patterns in "Straight, No Chaser," the circuitous line of "Criss Cross," and the absurdist melodic shape of "Four in One" are clearly outside of keyboard conventions, the product of pure imagination. It is precisely the unfamiliarity and seeming incongruity of Monk's technique that articulates the tension necessary to confirm the sublime. As the British philosopher Francis Bacon offered nearly four hundred years earlier, "There is no exquisite beauty without some strangeness in proportion."

There's something to be said about the unusual ensembles employed in these sessions as well. Names like Danny Quebec West, Billy Smith, and George Taitt may mean nothing to us today, and the reputations of Idrees Sulieman or Sahib Shihab may fade over time, but they provided Monk with a fascinating broader palette as he developed these pieces for recording than he was later accustomed to work with. Thus we have the strange horn voicings of "Thelonious" (followed by Monk's cubist phrasing and revealing stride episode), the tangy out-chorus of "Skippy," and the almost claustrophobically dissonant harmonies of "Hornin' In" and "Sixteen" - arrangements not to be repeated, and which induce some regret that Monk limited his working group to a single saxophonist over the years. (On that point, Misha Mengelberg loved to pronounce Lucky Thompson as the most compatible saxophonist that Monk ever had, however briefly.)

Truly creative artists have greater insight into the process and necessity of their efforts than do we mere mortals, which may be why Gertrude Stein's statement (from Composition as Explanation, written in 1925-26), having nothing to do with Monk, may have everything to do with Monk; that is, "Everything is the same except composition and as the composition is different and always going to be different everything is not the same." "-Art Lange, Chicago, September 2022

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Thelonious Monk "Thelonious Sphere Monk. October 10, 1917-February 17, 1982. With the arrival Thelonious Sphere Monk, modern music-let alone modern culture--simply hasn't been the same. Recognized as one of the most inventive pianists of any musical genre, Monk achieved a startlingly original sound that even his most devoted followers have been unable to successfully imitate. His musical vision was both ahead of its time and deeply rooted in tradition, spanning the entire history of the music from the "stride" masters of James P. Johnson and Willie "the Lion" Smith to the tonal freedom and kinetics of the "avant garde." And he shares with Edward "Duke" Ellington the distinction of being one of the century's greatest American composers. At the same time, his commitment to originality in all aspects of life-in fashion, in his creative use of language and economy of words, in his biting humor, even in the way he danced away from the piano-has led fans and detractors alike to call him "eccentric," "mad" or even "taciturn." Consequently, Monk has become perhaps the most talked about and least understood artist in the history of jazz. Born on October 10, 1917, in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, Thelonious was only four when his mother and his two siblings, Marion and Thomas, moved to New York City. Unlike other Southern migrants who headed straight to Harlem, the Monks settled on West 63rd Street in the "San Juan Hill" neighborhood of Manhattan, near the Hudson River. His father, Thelonious, Sr., joined the family three years later, but health considerations forced him to return to North Carolina. During his stay, however, he often played the harmonica, 'Jew's harp," and piano-all of which probably influenced his son's unyielding musical interests. Young Monk turned out to be a musical prodigy in addition to a good student and a fine athlete. He studied the trumpet briefly but began exploring the piano at age nine. He was about nine when Marion's piano teacher took Thelonious on as a student. By his early teens, he was playing rent parties, sitting in on organ and piano at a local Baptist church, and was reputed to have won several "amateur hour" competitions at the Apollo Theater. ,Admitted to Peter Stuyvesant, one of the city's best high schools, Monk dropped out at the end of his sophomore year to pursue music and around 1935 took a job as a pianist for a traveling evangelist and faith healer. Returning after two years, he formed his own quartet and played local bars and small clubs until the spring of 1941, when drummer Kenny Clarke hired him as the house pianist at Minton's Playhouse in Harlem. Minton's, legend has it, was where the "bebop revolution" began. The after-hours jam sessions at Minton's, along with similar musical gatherings at Monroe's Uptown House, Dan Wall's Chili Shack, among others, attracted a new generation of musicians brimming with fresh ideas about harmony and rhythm-notably Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Mary Lou Williams, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, Max Roach, Tadd Dameron, and Monk's close friend and fellow pianist, Bud Powell. Monk's harmonic innovations proved fundamental to the development of modern jazz in this period. Anointed by some critics as the "High Priest of Bebop," several of his compositions ("52nd Street Theme," "Round Midnight," "Epistrophy" [co-written with Kenny Clarke and originally titled "Fly Right" and then "Iambic Pentameter"], "I Mean You") were favorites among his contemporaries. Thelonious Monk StyleYet, as much as Monk helped usher in the bebop revolution, he also charted a new course for modern music few were willing to follow. Whereas most pianists of the bebop era played sparse chords in the left hand and emphasized fast, even eighth and sixteenth notes in the right hand, Monk combined an active right hand with an equally active left hand, fusing stride and angular rhythms that utilized the entire keyboard. And in an era when fast, dense, virtuosic solos were the order of the day, Monk was famous for his use of space and silence. In addition to his unique phrasing and economy of notes, Monk would "lay out" pretty regularly, enabling his sidemen to experiment free of the piano's fixed pitches. As a composer, Monk was less interested in writing new melodic lines over popular chord progressions than in creating a whole new architecture for his music, one in which harmony and rhythm melded seamlessly with the melody. "Everything I play is different," Monk once explained, "different melody, different harmony, different structure. Each piece is different from the other. . . . [W]hen the song tells a story, when it gets a certain sound, then it's through . . . completed." ,Despite his contribution to the early development of modern jazz, Monk remained fairly marginal during the 1940s and early 1950s. Besides occasional gigs with bands led by Kenny Clarke, Lucky Millinder, Kermit Scott, and Skippy Williams, in 1944 tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins was the first to hire Monk for a lengthy engagement and the first to record with him. Most critics and many musicians were initially hostile to Monk's sound. Blue Note, then a small record label, was the first to sign him to a contract. Thus, by the time he went into the studio to lead his first recording session in 1947, he was already thirty years old and a veteran of the jazz scene for nearly half of his life. But he knew the scene and during the initial two years with Blue Note had hired musicians whom he believed could deliver. Most were not big names at the time but they proved to be outstanding musicians, including trumpeters Idrees Sulieman and George Taitt; twenty-two year-old Sahib Shihab and seventeen-year-old Danny Quebec West on alto saxophones; Billy Smith on tenor; and bassists Gene Ramey and John Simmons. On some recordings Monk employed veteran Count Basie drummer Rossiere "Shadow" Wilson; on others, the drum seat was held by well-known bopper Art Blakey. His last Blue Note session as a leader in 1952 finds Monk surrounded by an all-star band, including Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Lou Donaldson (alto), "Lucky" Thompson (tenor), Nelson Boyd (bass), and Max Roach (drums). In the end, although all of Monk's Blue Note sides are hailed today as some of his greatest recordings, at the time of their release in the late 1940s and early 1950s, they proved to be a commercial failure. Harsh, ill-informed criticism limited Monk's opportunities to work-opportunities he desperately needed especially after his marriage to Nellie Smith in 1947, and the birth of his son, Thelonious, Jr., in 1949. Monk found work where he could, but he never compromised his musical vision. His already precarious financial situation took a turn for the worse in August of 1951, when he was falsely arrested for narcotics possession, essentially taking the rap for his friend Bud Powell. Deprived of his cabaret card-a police-issued "license" without which jazz musicians could not perform in New York clubs-Monk was denied gigs in his home town for the next six years. Nevertheless, he played neighborhood clubs in Brooklyn-most notably, Tony's Club Grandean, sporadic concerts, took out-of-town gigs, composed new music, and made several trio and ensemble records under the Prestige Label (1952-1954), which included memorable performances with Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, and Milt Jackson. In the fall of1953, he celebrated the birth of his daughter Barbara, and the following summer he crossed the Atlantic for the first time to play the Paris Jazz Festival. During his stay, he recorded his first solo album for Vogue. These recordings would begin to establish Monk as one of the century's most imaginative solo pianists. In 1955, Monk signed with a new label, Riverside, and recorded several outstanding LP's which garnered critical attention, notably Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington, The Unique Thelonious Monk, Brilliant Corners, Monk's Music and his second solo album, Thelonious Monk Alone. In 1957, with the help of his friend and sometime patron, the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, he had finally gotten his cabaret card restored and enjoyed a very long and successful engagement at the Five Spot Café with John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Wilbur Ware and then Ahmed Abdul-Malik on bass, and Shadow Wilson on drums. From that point on, his career began to soar; his collaborations with Johnny Griffin, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey, Clark Terry, Gerry Mulligan, and arranger Hall Overton, among others, were lauded by critics and studied by conservatory students. Monk even led a successful big band at Town Hall in 1959. It was as if jazz audiences had finally caught up to Monk's music. By 1961, Monk had established a more or less permanent quartet consisting of Charlie Rouse on tenor saxophone, John Ore (later Butch Warren and then Larry Gales) on bass, and Frankie Dunlop (later Ben Riley) on drums. He performed with his own big band at Lincoln Center (1963), and at the Monterey Jazz Festival, and the quartet toured Europe in 1961 and Japan in 1963. In 1962, Monk had also signed with Columbia records, one of the biggest labels in the world, and in February of 1964 he became the third jazz musician in history to grace the cover of Time Magazine. However, with fame came the media's growing fascination with Monk's alleged eccentricities. Stories of his behavior on and off the bandstand often overshadowed serious commentary about his music. The media helped invent the mythical Monk-the reclusive, naïve, idiot savant whose musical ideas were supposed to be entirely intuitive rather than the product of intensive study, knowledge and practice. Indeed, his reputation as a recluse (Time called him the "loneliest Monk") reveals just how much Monk had been misunderstood. As his former sideman, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, explained, Monk was somewhat of a homebody: "If Monk isn't working he isn't on the scene. Monk stays home. He goes away and rests." Unlike the popular stereotypes of the jazz musician, Monk was devoted to his family. He appeared at family events, played birthday parties, and wrote playfully complex songs for his children: "Little Rootie Tootie" for his son, "Boo Boo's Birthday" and "Green Chimneys" for his daughter, and a Christmas song titled "A Merrier Christmas." The fact is, the Monk family held together despite long stretches without work, severe money shortages, sustained attacks by critics, grueling road trips, bouts with illness, and the loss of close friends. During the 1960s, Monk scored notable successes with albums such as Criss Cross, Monk's Dream, It's Monk Time, Straight No Chaser, and Underground. But as Columbia/CBS records pursued a younger, rock-oriented audience, Monk and other jazz musicians ceased to be a priority for the label. Monk's final recording with Columbia was a big band session with Oliver Nelson's Orchestra in November of 1968, which turned out to be both an artistic and commercial failure. Columbia's disinterest and Monk's deteriorating health kept the pianist out of the studio. In January of 1970, Charlie Rouse left the band, and two years later Columbia quietly dropped Monk from its roster. For the next few years, Monk accepted fewer engagements and recorded even less. His quartet featured saxophonists Pat Patrick and Paul Jeffrey, and his son Thelonious, Jr., took over on drums in 1971. That same year through 1972, Monk toured widely with the "Giants of Jazz," a kind of bop revival group consisting of Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Al McKibbon and Art Blakey, and made his final public appearance in July of 1976. Physical illness, fatigue, and perhaps sheer creative exhaustion convinced Monk to give up playing altogether. On February 5, 1982, he suffered a stroke and never regained consciousness; twelve days later, on February 17th, he died. Today Thelonious Monk is widely accepted as a genuine master of American music. His compositions constitute the core of jazz repertory and are performed by artists from many different genres. He is the subject of award winning documentaries, biographies and scholarly studies, prime time television tributes, and he even has an Institute created in his name. The Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz was created to promote jazz education and to train and encourage new generations of musicians. It is a fitting tribute to an artist who was always willing to share his musical knowledge with others but expected originality in return."-Robin D. G. Kelley Ph.D. ^ Hide Bio for Thelonious Monk • Show Bio for Art Blakey "Arthur Blakey (October 11, 1919 - October 16, 1990) was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s. Blakey made a name for himself in the 1940s in the big bands of Fletcher Henderson and Billy Eckstine. He then worked with bebop musicians Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie. In the mid-1950s, Horace Silver and Blakey formed the Jazz Messengers, a group that the drummer was associated with for the next 35 years. The group was formed as a collective of contemporaries, but over the years the band became known as an incubator for young talent, including Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Johnny Griffin, Curtis Fuller, Chuck Mangione, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Cedar Walton, Woody Shaw, Terence Blanchard, and Wynton Marsalis. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz calls the Jazz Messengers "the archetypal hard bop group of the late 50s". Blakey was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame (in 1981). Posthumously, he was inducted into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1991 and the Grammy Hall of Fame (in 1998 and 2001). He was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005." ^ Hide Bio for Art Blakey • Show Bio for Sahib Shihab "Sahib Shihab (born Edmund Gregory; June 23, 1925 - October 24, 1989) was an American jazz and hard bop saxophonist (baritone, alto, and soprano) and flautist. He variously worked with Luther Henderson, Thelonious Monk, Fletcher Henderson, Tadd Dameron, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, John Coltrane and Quincy Jones among others. He was born in Savannah, Georgia, United States. Edmund Gregory first played alto saxophone professionally for Luther Henderson aged 13, and studied at the Boston Conservatory, and to perform with trumpeter Roy Eldridge. He played lead alto with Fletcher Henderson in the mid-1940s. He was one of the first jazz musicians to convert to Islam and changed his name in 1947. He belonged to the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam. - American jazz double bassist During the late 1940s, Shihab played with Thelonious Monk, and on July 23, 1951 he recorded with Monk (later issued on the album Genius of Modern Music: Volume 2). During this period, he also appeared on recordings by Art Blakey, Kenny Dorham and Benny Golson. The invitation to play with Dizzy Gillespie's big band in the early 1950s was of particular significance, as it marked Shihab's switch to baritone. On August 12, 1958, Shihab was one of the musicians photographed by Art Kane in his photograph known as "A Great Day in Harlem". In 1959, he toured Europe with Quincy Jones, after becoming disillusioned with racial politics in United States and ultimately settled in Scandinavia, first in Stockholm, Sweden and from 1964 in Copenhagen, Denmark. He worked for Copenhagen Polytechnic and wrote scores for television, cinema and theatre. He wrote a ballet based on the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale, The Red Shoes. In Denmark, Shihab performed with local musicians such as the bass player Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen amongst others. Together with pianist Kenny Drew, he ran a publishing firm and record company. In 1961, he joined the Kenny Clarke/Francy Boland Big Band and remained a member of the band for the 12 years it existed. He married a Danish woman and raised a family in Europe. In the Eurovision Song Contest 1966, Shihab accompanied Lill Lindfors and Svante Thuresson on stage for the Swedish entry "Nygammal Vals". In 1973, Shihab returned to the United States for a three-year hiatus, working as a session musician for rock and pop artists and undertaking work as a copyist for local musicians. He spent his remaining years between New York and Copenhagen and played in a partnership with Art Farmer. He also led his own jazz combo called Dues. From 1986, Shihab was a visiting artist at Rutgers University. Shihab died from liver cancer on October 24, 1989, in Nashville, Tennessee, United States, aged 64." ^ Hide Bio for Sahib Shihab • Show Bio for Milt Jackson "Milton Jackson (January 1, 1923 – October 9, 1999), nicknamed "Bags", was an American jazz vibraphonist, usually thought of as a bebop player, although he performed in several jazz idioms. He is especially remembered for his cool swinging solos as a member of the Modern Jazz Quartet and his penchant for collaborating with hard bop and post-bop players. A very expressive player, Jackson differentiated himself from other vibraphonists in his attention to variations on harmonics and rhythm. He was particularly fond of the twelve-bar blues at slow tempos. He preferred to set his vibraphone's oscillator to a low 3.3 revolutions per second (as opposed to Lionel Hampton's speed of 10 revolutions per second) for a more subtle tremolo. On occasion, Jackson also sang and played piano. ackson was born on January 1, 1923, in Detroit, Michigan, United States, the son of Manley Jackson and Lillie Beaty Jackson. Like many of his contemporaries, he was surrounded by music from an early age, particularly that of religious meetings: "Everyone wants to know where I got that funky style. Well, it came from church. The music I heard was open, relaxed, impromptu soul music" (quoted in Nat Hentoff's liner notes to Plenty, Plenty Soul). He started on guitar when he was seven, and then on piano at 11. While attending Miller High School, he played drums in addition to timpani and violin and also sang in the choir. At 16, he sang professionally in a local touring gospel quartet called the Evangelist Singers. He took up the vibraphone at 16 after hearing Lionel Hampton play the instrument in Benny Goodman's band. Jackson was discovered by Dizzy Gillespie, who hired him for his sextet in 1945, then his larger ensembles. Jackson quickly acquired experience working with the most important figures in jazz of the era, including Woody Herman, Howard McGhee, Thelonious Monk, and Charlie Parker. In the Gillespie big band, Jackson fell into a pattern that led to the founding of the Modern Jazz Quartet: Gillespie maintained a former swing tradition of a small group within a big band, and his included Jackson, pianist John Lewis, bassist Ray Brown, and drummer Kenny Clarke (considered a pioneer of the ride cymbal timekeeping that became the signature for bop and most jazz to follow) while the brass and reeds took breaks. When they decided to become a working group in their own right, around 1950, the foursome was known at first as the Milt Jackson Quartet, becoming the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) in 1952. By that time Percy Heath had replaced Ray Brown. Known at first for featuring Jackson's blues-heavy improvisations almost exclusively, in time the group came to split the difference between these and Lewis's more ambitious musical ideas. Lewis had become the group's musical director by 1955, the year Clarke departed in favour of Connie Kay, boiling the quartet down to a chamber jazz style, that highlighted the lyrical tension between Lewis's mannered, but roomy, compositions, and Jackson's unapologetic swing.[citation needed] The MJQ had a long independent career of some two decades until disbanding in 1974, when Jackson split with Lewis. The group reformed in 1981, however, and continued until 1993, after which Jackson toured alone, performing in various small combos, although agreeing to periodic MJQ reunions. From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, Jackson recorded for Norman Granz's Pablo Records, including Jackson, Johnson, Brown & Company (1983), featuring Jackson with J. J. Johnson on trombone, Ray Brown on bass, backed by Tom Ranier on piano, guitarist John Collins, and drummer Roy McCurdy. In 1989, Jackson was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music from the Berklee College of Music. His composition "Bags' Groove" is a jazz standard ("Bags" was a nickname given to him by a bass player in Detroit. "Bags" referred to the bags under his eyes). He was featured on the NPR radio program Jazz Profiles. Some of his other signature compositions include "The Late, Late Blues" (for his album with Coltrane, Bags & Trane), "Bluesology" (an MJQ staple), and "Bags & Trane".[citation needed] Jackson died of liver cancer in Manhattan, New York, at the age of 76. He was married to Sandra Whittington from 1959 until his death; the couple had a daughter." ^ Hide Bio for Milt Jackson • Show Bio for Al McKibbon "Al McKibbon (January 1, 1919 - July 29, 2005) was an American jazz double bassist, known for his work in bop, hard bop, and Latin jazz. In 1947, after working with Lucky Millinder, Tab Smith, J. C. Heard, and Coleman Hawkins, he replaced Ray Brown in Dizzy Gillespie's band, in which he played until 1950. In the 1950s he recorded with the Miles Davis nonet, Earl Hines, Count Basie, Johnny Hodges, Thelonious Monk, Mongo Santamaria, George Shearing, Cal Tjader, Herbie Nichols and Hawkins. McKibbon was credited with interesting Tjader in Latin music while he played in Shearing's group. McKibbon has always been highly regarded (among other signs of this regard, he was the bassist for the Giants of Jazz), and continued to perform until 2004. In 1999, the first album in his own name, Tumbao Para Los Congueros De Mi Vida, was released. McKibbon's second album, Black Orchid (Nine Yards Music), was released in 2004 and was recorded at Icon Recording Studios, Hollywood, California. The album was recorded and mixed by studio owner Andrew Troy and Assistant Engineer - Aaron Kaplay, 2nd Assistant Engineer - Pablo Solorzano. He also wrote the Afterword to Raul Fernandez' book, Latin Jazz, part of the Smithsonian Institution's series of exhibitions on jazz." ^ Hide Bio for Al McKibbon • Show Bio for Kenny Dorham "McKinley Howard "Kenny" Dorham (August 30, 1924 - December 5, 1972) was an American jazz trumpeter, singer, and composer. Dorham's talent is frequently lauded by critics and other musicians, but he never received the kind of attention or public recognition from the jazz establishment that many of his peers did. For this reason, writer Gary Giddins said that Dorham's name has become "virtually synonymous with underrated." Dorham composed the jazz standard "Blue Bossa", which first appeared on Joe Henderson's album Page One. Dorham was one of the most active bebop trumpeters. He played in the big bands of Lionel Hampton, Billy Eckstine, Dizzy Gillespie, and Mercer Ellington and the quintet of Charlie Parker. He joined Parker's band in December 1948. He was a charter member of the original cooperative Jazz Messengers. He also recorded as a sideman with Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, and he replaced Clifford Brown in the Max Roach Quintet after Brown's death in 1956. In addition to sideman work, Dorham led his own groups, including the Jazz Prophets (formed shortly after Art Blakey took over the Jazz Messengers name). The Jazz Prophets, featuring a young Bobby Timmons on piano, bassist Sam Jones, and tenorman J. R. Monterose, with guest Kenny Burrell on guitar, recorded a live album 'Round About Midnight at the Cafe Bohemia in 1956 for Blue Note. In 1963 Dorham added the 26-year-old tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson to his group, which later recorded Una Mas (the group also featured a young Tony Williams). The friendship between the two musicians led to a number of other albums, such as Henderson's Page One, Our Thing and In 'n Out. Dorham recorded frequently throughout the 1960s for Blue Note and Prestige Records, as leader and as sideman for Henderson, Jackie McLean, Cedar Walton, Andrew Hill, Milt Jackson and others. Dorham's later quartet consisted of some well-known jazz musicians: Tommy Flanagan (piano), Paul Chambers (double bass), and Art Taylor (drums). Their recording debut was Quiet Kenny for the Prestige Records' New Jazz label, an album which featured mostly ballads. An earlier quartet featuring Dorham as co-leader with alto saxophone player Ernie Henry had released an album together under the name "Kenny Dorham/Ernie Henry Quartet." They produced the album 2 Horns / 2 Rhythm for Riverside Records in 1957 with double bassist Eddie Mathias and drummer G.T. Hogan. In 1990 the album was re-released on CD under the name "Kenny Dorham Quartet featuring Ernie Henry." During his final years Dorham suffered from kidney disease, from which he died on December 5, 1972, aged 48. On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Kenny Dorham among hundreds of artists who recorded for record labels whose master recordings were reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire." ^ Hide Bio for Kenny Dorham • Show Bio for Lou Donaldson "Lou Donaldson (born November 1, 1926) is an American retired jazz alto saxophonist. He is best known for his soulful, bluesy approach to playing the alto saxophone, although in his formative years he was, as many were of the bebop era, heavily influenced by Charlie Parker. Donaldson was born in Badin, North Carolina, United States. He attended North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro in the early 1940s. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II and was trained at the Great Lakes bases in Chicago where he was introduced to bop music in the lively club scene. At the war's conclusion, he returned to Greensboro, where he worked club dates with the Rhythm Vets, a combo composed of A and T students who had served in the U.S. Navy. The band recorded the soundtrack to a musical comedy featurette, Pitch a Boogie Woogie, in Greenville, North Carolina, in the summer of 1947. The movie had a limited run at black audience theatres in 1948 but its production company, Lord-Warner Pictures, folded and never made another film. Pitch a Boogie Woogie was restored by the American Film Institute in 1985 and re-premiered on the campus of East Carolina University in Greenville the following year. Donaldson and the surviving members of the Vets performed a reunion concert after the film's showing. In the documentary made on Pitch by UNC-TV, Boogie in Black and White, Donaldson and his musical cohorts recall the film's making—he originally believed that he had played clarinet on the soundtrack. A short piece of concert footage from a gig in Fayetteville, North Carolina, is included in the documentary. Donaldson's first jazz recordings were with the Charlie Singleton Orchestra in 1950 and then with bop emissaries Milt Jackson and Thelonious Monk in 1952, and he participated in several small groups with other prominent jazz musicians such as trumpeter Blue Mitchell, pianist Horace Silver, and drummer Art Blakey. In 1953, he also recorded sessions with the trumpet virtuoso Clifford Brown, and Philly Joe Jones. He was a member of Art Blakey's Quintet and appeared on some of their best regarded albums, including the two albums recorded at Birdland in February 1954 Night at Birdland. He was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame on October 11, 2012. Also in 2012, he was named a NEA Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2018, he declared himself retired, having performed his final shows in 2017. On November 2, 2021, he made a public appearance at a 95th birthday tribute show at Dizzy’s Club." ^ Hide Bio for Lou Donaldson • Show Bio for Lucky Thompson "Eli "Lucky" Thompson (June 16, 1924 – July 30, 2005) was an American jazz tenor and soprano saxophonist whose playing combined elements of swing and bebop. While John Coltrane usually receives the most credit for bringing the soprano saxophone out of obsolescence in the early 1960s, Thompson (along with Steve Lacy) embraced the instrument earlier than Coltrane. Thompson was born in Columbia, South Carolina, and moved to Detroit, Michigan, during his childhood. Thompson had to raise his siblings after his mother died, and he practiced saxophone fingerings on a broom handle before acquiring his first instrument. He joined Erskine Hawkins' band in 1942 upon graduating from high school. After playing with the swing orchestras of Lionel Hampton, Don Redman, Billy Eckstine (alongside Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker), Lucky Millinder, and Count Basie, he worked in rhythm and blues and then established a career in bebop and hard bop, working with Kenny Clarke, Miles Davis, Gillespie and Milt Jackson. Ben Ratliff notes that Thompson "connected the swing era to the more cerebral and complex bebop style. His sophisticated, harmonically abstract approach to the tenor saxophone built off that of Don Byas and Coleman Hawkins; he played with beboppers, but resisted Charlie Parker's pervasive influence." He showed these capabilities as sideman on many albums recorded during the mid-1950s, such as Stan Kenton's Cuban Fire!, and those under his own name. He recorded with Parker (on two Los Angeles Dial Records sessions) and on Miles Davis's hard bop Walkin' session. Thompson recorded albums as leader for ABC Paramount and Prestige and as a sideman on records for Savoy Records with Jackson as leader. Thompson was strongly critical of the music business, later describing promoters, music producers and record companies as "parasites" or "vultures". This, in part, led him to move to Paris, where he lived and made several recordings between 1957 and 1962. During this time, he began playing soprano saxophone. Thompson returned to New York, then lived in Lausanne, Switzerland, from 1968 until 1970, and recorded several albums there including A Lucky Songbook in Europe. He taught at Dartmouth College in 1973 and 1974, then completely left the music business. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Lucky Thompson • Show Bio for Max Roach "Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 - August 16, 2007) was an American jazz drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in history. He worked with many famous jazz musicians, including Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Abbey Lincoln, Dinah Washington, Charles Mingus, Billy Eckstine, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, and Booker Little. He was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1992. Roach also co-led a pioneering quintet along with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the percussion ensemble M'Boom. He made numerous musical statements relating to the civil rights movement. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Max Roach

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/18/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Thelonious 3:02

2. 'Round Midnight 3:13

3. Well You Needn't 2:59

4. Off Minor 3:03

5. In Walked Bud 2:58

6. Epistrophy 3:09

7. Ruby My Dear 3:10

8. Evidence 2:34

9. Humph 2:54

10. I Mean You 3:23

11. Misterioso 2:46

12. I Mean You 3:10

13. Who Knows 2:45

14. Four In One 3:30

15. Straight No Chaser 2:59

16. Criss-Cross 2:57

17. Eronel 3:06

18. Ask Me Now 3:16

19. Skippy 3:02

20. Let's Cool One 3:50

21. Hornin' In 3:14

22. Introspection 3:14

23. Sixteen 3:30

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

Trio Recordings

Quartet Recordings

Quintet Recordings

Sextet Recordings

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

New in Improvised Music

Jazz & Improvisation Based on Compositions

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![BlueRing Improvisers: Materia [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36513.jpg)

![Wheelhouse (Rempis / Adasiewicz / McBride): House And Home [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36462.jpg)

![+DOG+: The Light Of Our Lives [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36009.jpg)

![Parker, Evan / Jean-Marc Foussat: Insolence [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36398.jpg)

![Deupree, Jerome / Sylvie Courvoisier / Lester St. Louis / Joe Morris: Canyon [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36404.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)