Reissuing two albums showing trumpeter Don Cherry's musical evolution through the 1960s, recorded two years apart--Where is Brooklyn from NY in 1966, and Eternal Rhythm recorded in Germany in 1968--demonstrating the development of his style from Ornette-influenced free jazz into music influenced by Northern Indian music and the percussion of Southeast Asia.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Don Cherry-cornet, gamelan, flute, performer, bells, voice

Pharoah Sanders-tenor saxophone, piccolo

Henry Grimes-double bass

Edward Blackwell-drums

Bernt Rosengren-tenor saxophone, flute, oboe, clarinet

Albert Mangelsdorff-trombone

Eje Thelin-trombone

Karl Berger-piano, vibraphone, gamelan

Joachim Kuhn-piano, prepared piano

Sonny Sharrock-guitar

Arild Andersen-double bass

Jacques Thollot-drums, gamelan, bells, voice

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156112921

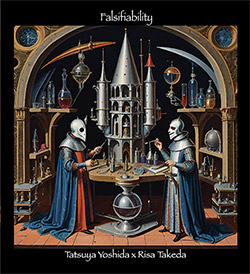

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1129

Squidco Product Code: 31703

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2022

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Tracks 1-5 recorded in the US, on November 11th, 1966.

Tracks 6 and 7 recorded in Germany, on November 11th and 12th, 1968. Where Is Brooklyn? originally released in 1969 on the Blue Note label as a vinyl album with catalog code BST 84311. Eternal Rhythm originally release in 1969 on the German MPS Records label as a vinyl album with catalog code MPS 15204.

"These sessions were recorded exactly two years apart, in early November 1966 and 1968 (both were released in 1969). While they can't be called "bookends" by any means, they do bracket a remarkable period in Don Cherry's musical evolution, on his journey from the more strictly jazz environments, as adventurous as they were, of Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler and others, to a philosophy that embraced many non-Western traditions. While these included various African forms, especially those of west-central Africa, some of which had been previously investigated by musicians ranging from Art Blakey to Randy Weston among others, Cherry extended his research into Northern Indian music, including singing and, as brilliantly evidenced in 'Eternal Rhythm', the percussion music of Southeast Asia.

Truth to tell, it's difficult to hear any real portent of things to come in the Where Is Brooklyn? session. Rather, it reads more as a culmination and arguable highpoint of Cherry's post-Ornette explorations, featuring short, tight themes-all composed by Cherry, largely in an "Ornette-ish" vein-and relatively free improvisations thereon. Pharoah Sanders, who would do his own investigation of non-Western musics in upcoming years, effortlessly glides from volcanic to delicately sensitive, the latter especially clear in the closing minute or so of the first track, 'Awake Nu', where he and Cherry engage in a touching dialogue. Both Grimes and Blackwell play as strongly and with as much inspiration as they ever had, the latter evincing his uniquely rounded, tonal approach, part of his own direct lineage from West Africa via New Orleans. On the longest track, 'Unite', Sanders switches for a time from tenor saxophone to piccolo flute, anticipating the sound territories Cherry would soon map with his own arsenal of wooden and metal flutes. In sum, Where Is Brooklyn? is a vibrant, muscular and rambunctious recording, a fine document summarizing lessons learned over the preceding decade, sharpened to a luminous degree of precision.

There's not a lot of recorded evidence between the two dates, though what there is more than hints at Cherry's direction, including a 1967 soundtrack for a film by Jean-Noël Delamarre, released in 2017 as 'Music, Wisdom, Love 1969' where the piano parts (probably played by Karl Berger) seem to reflect the influence of Abdullah Ibrahim (then known as Dollar Brand) and Cherry's birdcall-like flute stylings are heard. As well, he ventured to Tunisia to take part in a festival with George Gruntz which included local musicians. By July of 1968, when the 'Summer House Sessions' were recorded in Sweden (unreleased until 2021), the integration of nonwestern forms was in full flower while still retaining a number of contemporary jazz structures. In the company of a wide range of musicians, including tenorist Bernt Rosengren and drummer Jacques Thollot, both of whom would be part of the Eternal Rhythm band, Cherry launches lengthy, ever-unspooling work that morphs from one theme to another, very much a tapestry, to an extent reflected in his wife Moki's visual art. 'Live in Stockholm' (Caprice, 2013), which includes an almost 50-minute set from September 2, resides in a similar area: familiar enough jazz forms interspersed with travels down some "exotic" byways.

A recording exists of the Eternal Rhythm ensemble from two days before the present session, intriguingly including Sanders in the cast, performing largely the same material. But while very energetic and enjoyable, it's much less precise, even meandering at times, perhaps partly an artifact of poorer recording quality. The session here begins with the by now familiar delicate, fluttering flute playing before, several minutes in, emerging into entirely new territory occupied by gamelan instruments, hitherto unheard in Cherry's music (perhaps introduced by Karl Berger?), creating a wonderful welter of bellsounds over a seven-note Indian-influenced melody. The section of the album-length suite titled, "Sonny Sharrock" follows and, indeed, the guitarist is in full-on shards-of-sound form, sending forth splintering showers of notes, leading into the fanfare-like playing of Cherry, now on cornet, and the tenor saxophone of Rosengren. After an apparent edit (the recording was culled from two days of sessions), Cherry returns on flutes to an exposition of the theme that began the set, a gorgeous, dancing melody that seems derived not from a specific tradition but from many at once.

Part Two of the suite starts with a riotous free-for-all

featuring Joachim Kühn's piano, the two trombonists and Berger's vibes before segueing into an even denser, more complex jungle of gamelan and other percussion, a breathing, even seething mass of sound unlike anything heard in jazz prior to that point. The ensemble achieves such a thickness of sound, such a roiling richness, that it seems almost anything might emerge. The music shifts, slows, almost lurches into a steady, measured rhythm which, surprisingly but also crucially, congeals into a blues ('Screaming J'), anchored by Anderson and Thollot, brilliantly commented on by Cherry and Kühn, some of the former's deepest and most anguished playing yet. By bringing these worldwide investigations back to the blues, Cherry emphasizes and reinforces that music's extra-Western roots.

Cherry's ideas behind 'Eternal Rhythm' clearly helped set the stage for further combinations of so-called world music and jazz by a wide range of musicians but few, if any, reached this level of imagination, integrity and sheer, wondrous musicality."-Brian Olewnick, February 2022

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Don Cherry "Imagination and a passion for exploration made Don Cherry one of the most influential jazz musicians of the late 20th century. A founding member of Ornette Coleman's groundbreaking quartet of the late '50s, Cherry continued to expand his musical vocabulary until his death in 1995. In addition to performing and recording with his own bands, Cherry worked with such top-ranked jazz musicians as Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and Gato Barbieri. Cherry's most prolific period came in the late '70s and early '80s when he joined Nana Vasconcelos and Collin Walcott in the worldbeat group Codona, and with former bandmates Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell, and saxophonist Dewey Redman in the Coleman-inspired group Old and New Dreams. Cherry later worked with Vasconcelos and saxophonist Carlos Ward in the short-lived group Nu. The Avant-Garde Born in Oklahoma City in 1936, he first attained prominence with Coleman, with whom he began playing around 1957. At that time Cherry's instrument of choice was a pocket trumpet (or cornet) -- a miniature version of the full-sized model. The smaller instrument -- in Cherry's hands, at least -- got a smaller, slightly more nasal sound than is typical of the larger horn. Though he would play a regular cornet off and on throughout his career, Cherry remained most closely identified with the pocket instrument. Cherry stayed with Coleman through the early '60s, playing on the first seven (and most influential) of the saxophonist's albums. In 1960, he recorded The Avant-Garde with John Coltrane. After leaving Coleman's band, Cherry played with Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, and Albert Ayler. In 1963-1964, Cherry co-led the New York Contemporary Five with Shepp and John Tchicai. With Gato Barbieri, Cherry led a band in Europe from 1964-1966, recording two of his most highly regarded albums, Complete Communion and Symphony for Improvisers. Cherry began the '70s by teaching at Dartmouth College in 1970, and recorded with the Jazz Composer's Orchestra in 1973. He lived in Sweden for four years, and used the country as a base for his travels around Europe and the Middle East. Cherry became increasingly interested in other, mostly non-Western styles of music. In the late '70s and early '80s, he performed and recorded with Codona, a cooperative group with percussionist Nana Vasconcelos and multi-instrumentalist Collin Walcott. Codona's sound was a pastiche of African, Asian, and other indigenous musics. Art Deco Concurrently, Cherry joined with ex-Coleman associates Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell, and Dewey Redman to form Old and New Dreams, a band dedicated to playing the compositions of their former employer. After the dissolution of Codona, Cherry formed Nu with Vasconcelos and saxophonist Carlos Ward. In 1988, he made Art Deco, a more traditional album of acoustic jazz, with Haden, Billy Higgins, and saxophonist James Clay. Multikulti Until his death in 1995, Cherry continued to combine disparate musical genres; his interest in world music never abated. Cherry learned to play and compose for wood flutes, tambura, gamelan, and various other non-Western instruments. Elements of these musics inevitably found their way into his later compositions and performances, as on 1990's Multi Kulti, a characteristic celebration of musical diversity. As a live performer, Cherry was notoriously uneven. It was not unheard of for him to arrive very late for gigs, and his technique -- never great to begin with -- showed on occasion a considerable, perhaps inexcusable, decline. In his last years, especially, Cherry seemed less self-possessed as a musician. Yet his musical legacy is one of such influence that his personal failings fade in relative significance." ^ Hide Bio for Don Cherry • Show Bio for Pharoah Sanders "Pharoah Sanders (born October 13, 1940) is an American jazz saxophonist. Saxophonist Ornette Coleman once described him as "probably the best tenor player in the world." Emerging from John Coltrane's groups of the mid-1960s, Sanders is known for his overblowing, harmonic, and multiphonic techniques on the saxophone, as well as his use of "sheets of sound". Sanders is an important figure in the development of free jazz; Albert Ayler famously said: "Trane was the Father, Pharoah was the Son, I am the Holy Ghost". Pharoah Sanders was born Farrell Sanders on October 13, 1940 in Little Rock, Arkansas. His mother worked as a cook in a school cafeteria, and his father worked for the City of Little Rock. An only child, Sanders began his musical career accompanying church hymns on clarinet. His initial artistic accomplishments were in art, but when he was at Scipio Jones High School in North Little Rock, Sanders began playing the tenor saxophone. The band director, Jimmy Cannon, was also a saxophone player and introduced Sanders to jazz. When Cannon left, Sanders, although still a student, took over as the band director until a permanent director could be found. During the late 1950s, Sanders would often sneak into African-American clubs in downtown Little Rock to play with acts that were passing through. At the time, Little Rock was part of the touring route through Memphis, Tennessee, and Hot Springs for R&B and jazz musicians, including Junior Parker. Sanders found himself limited by the state’s segregation and the R&B and jazz standards that dominated the Little Rock music scene. After finishing high school in 1959, Sanders moved to Oakland, California, and lived with relatives. He briefly attended Oakland Junior College and studied art and music. Once outside the Jim Crow South, Sanders could play in both black and white clubs. His Arkansas connection stuck with him in the Bay Area with the nickname of “Little Rock.” It was also during this time that he met and befriended John Coltrane. Pharoah Sanders began his professional career playing tenor saxophone in Oakland, California. He moved to New York City in 1961 after playing with rhythm and blues bands. He received his nickname "Pharoah" from bandleader Sun Ra, with whom he was performing. After moving to New York, Sanders had been destitute: "He was often living on the streets, under stairs, where ever he could find to stay, his clothes in tatters." Sun Ra gave him a place to stay, bought him a new pair of green pants with yellow stripes (which Sanders hated but had to have), encouraged him to use the name 'Pharoah', and gradually worked him into the band." Sanders came to greater prominence playing with John Coltrane's band, starting in 1965, as Coltrane began adopting the avant-garde jazz of Albert Ayler, Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor. Sanders first performed with Coltrane on Ascension (recorded in June 1965), then on their dual-tenor recording Meditations (recorded in November 1965). After this Sanders joined Coltrane's final quintet, usually performing very lengthy, dissonant solos. Coltrane's later style was strongly influenced by Sanders. Although Sanders' voice developed differently from Coltrane, Sanders was strongly influenced by their collaboration. Spiritual elements such as the chanting in Om would later show up in many of Sanders' own works. Sanders would also go on to produce much free jazz, modified from Coltrane's solo-centric conception. In 1968 he participated in Michael Mantler and Carla Bley's Jazz Composer's Orchestra Association album The Jazz Composer's Orchestra, featuring Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry, Larry Coryell and Gato Barbieri. Pharoah's first album, Pharoah's First, wasn't what he expected. The musicians playing with him where much more straightforward than Sanders, which made the solos played by the other musicians a bit out of place. Starting in 1966 Sanders signed with Impulse! and recorded Tauhid that same year. His years with Impulse! caught the attention of jazz fans, critics, and musicians alike, including John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Albert Ayler. In the 1970s, Sanders continued to produce his own recordings and also continued to work with the likes of Alice Coltrane on her Journey In Satchidananda album. Most of Sanders' best-selling work was made in the late 1960s and early 1970s for Impulse Records, including the 30-minute wave-on-wave of free jazz "The Creator has a Master Plan" from the album Karma. This composition featured vocalist Leon Thomas's unique, "umbo weti" yodeling, and Sanders' key musical partner, pianist Lonnie Liston Smith, who worked with Sanders from 1969-1971. Other members of his groups in this period include bassist Cecil McBee, on albums such as Jewels of Thought, Izipho Zam, Deaf Dumb Blind and Thembi. Although supported by African-American radio, Sanders' brand of free jazz became less popular. From the experiments with African rhythms on the 1971 album Black Unity (with bassist Stanley Clarke) onwards he began to diversify his sound. In the late 1970s and 1980s, Sanders explored different musical modes including R&B (Love Will Find a Way), modal jazz, and hard bop. Sanders left Impulse! in 1973 and redirected his compositions back to earlier jazz conventions. He continued to explore the music of different cultures and refine his compositions. However, he found himself floating from label to label. He found a permanent home with a small label called Theresa in 1987, which was sold to Evidence in 1991. However Sanders would continue to be frustrated with record labels for most of the 1990s. Also during this time, he went to Africa for a cultural exchange program for the U.S. State Department. Sanders’s major-label return would finally come in 1995 when Verve Records released Message from Home, followed by Save Our Children (1998). But again, Sanders’s disgust with the recording business prompted him to leave the label. In 1992, Sanders appears on a reissue (Ed Kelly and Pharoah Sanders) for the Evidence label of a recording that he completed for Theresa Records in 1979 entitled Ed Kelly and Friend. The 1992 version contains extra tracks which feature Pharoah's pupil Robert Stewart (saxophonist). This was Stewart's first recording for a jazz label. In 1994 he traveled to Morocco to record the Bill Laswell-produced album The Trance Of Seven Colors with Gnawa musician Mahmoud Guinia. The same year, Sanders appeared on the Red Hot Organization's album, Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool, on the track "This is Madness" with Umar Bin Hassan and Abiodun Oyewole and the bonus track, "The Creator Has A Master Plan (Trip hop Remix)." The album was named "Album of the Year" by Time. Sanders worked with Laswell, Jah Wobble, and others on the albums Message From Home (1996) and Save Our Children (1999). In 1999, he complained in an interview that despite his pedigree, he had trouble finding work. In 1997 he was featured on several Tisziji Munoz albums also including Rashied Ali. In the 2000s, a resurgence of interest in jazz kept Sanders playing festivals including the 2007 Melbourne Jazz Festival and the 2008 Big Chill Festival, concerts, and releasing albums. He has a strong following in Japan, and in 2003 recorded with the band Sleep Walker. In 2000, Sanders released Spirits and, in 2003, a live album titled The Creator Has a Master Plan. He was awarded an NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for 2016 and was honored at a tribute concert in Washington DC on April 4, 2016." ^ Hide Bio for Pharoah Sanders • Show Bio for Henry Grimes "As of the beginning of 2016, master jazz musician Henry Grimes (acoustic bass, violin, poetry, illustrations) had played more than 615 concerts in 31 countries (including many festivals) since 2003, when he made his astonishing return to the music world after 35 years away. He was born and raised in Philadelphia and attended the Mastbaum School (1949-52) and Juilliard (1952-54). As a youngster in the '50's and early '60's, he came up in the music playing and touring with Willis "Gator Tail" Jackson, Arnett Cobb, "Bullmoose" Jackson, "Little" Willie John, King Curtis, and a number of other great R&B / soul musicians; but drawn to jazz, he went on to play, tour, and record with many great jazz musicians of that era, including Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Benny Goodman, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Haynes, Lee Konitz, Steve Lacy, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Sunny Murray, Sonny Rollins, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, Cecil Taylor, and McCoy Tyner. Sadly, a trip to the West Coast to work with Al Jarreau and Jon Hendricks went awry, leaving Henry in Los Angeles at the end of the '60's with a broken bass he couldn't pay to repair, so he sold it for a small sum and faded away from the music world. Many years passed with nothing heard from him, as he lived in his tiny rented room in an S.R.O. hotel in downtown Los Angeles, working as a manual laborer, custodian, and maintenance man, and writing many volumes of handwritten poetry. He was discovered there by a Georgia social worker in 2002 and was given a bass by William Parker, and after only a few weeks of ferocious woodshedding, Henry emerged from his room to begin playing concerts around Los Angeles and shortly afterwards made a triumphant return to New York City in May, 2003 to play in the Vision Festival. Since then, often working as a leader, he has played, toured, and / or recorded with many of this era's musical and literary heroes, such as Chris Abani, Rashied Ali, Geri Allen, Marshall Allen, Barry Altschul, Fred Anderson, Tatsu Aoki, Newman Taylor Baker, Billy Bang, Harrison Bankhead, Amiri Baraka, Joey Baron, Hamiet Bluiett, Dave Burrell, Roy Campbell Jr., Alex & Nels Cline, Cooper-Moore, Marilyn Crispell, Connie Crothers, Ted Curson, Andrew Cyrille, Thulani Davis, Toi Derricotte, Bill Dixon, Pierre Dorge, Hamid Drake, Paul Dunmall, Cornelius Eady, Kahil El'Zabar, Douglas Ewart, Bobby Few, Charles Gayle, Melvin Gibbs, Yoriyuki Harada, Craig Harris, Graham Haynes, Karma Mayet Johnson, Edward "Kidd" Jordan, Andrew Lamb, Nathaniel Mackey, Maria Mitchell, Nicole Mitchell, Roscoe Mitchell, Elaine Mitchener, Louis Moholo-Moholo, Meredith Monk [recording only], Jemeel Moondoc, Jason Moran, David Murray, Sunny Murray, Amina Claudine Myers, Zim Ngqawana, Kresten Osgood, William Parker, HPrizm (High Priest, Kyle Austin), Odean Pope, Avreeayl Ra, Tomeka Reid, Vernon Reid, Marc Ribot, Matana Roberts, Orphy Robinson, Brandon Ross, Lee Mixashawn Rozie, Mark Sanders, Rasul Siddik, Wadada Leo Smith, Warren Smith, Tyshawn Sorey, Sekou Sundiata, Tani Tabbal, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Aldo Tambellini, Greg Tate, Cecil Taylor (reunion), Chad Taylor, John Tchicai, Pat Thomas, Henry Threadgill, Edwin Torres, Dwight Trible, Jeff "Tain" Watts, Ed Wilkerson Jr., James Zollar, John Zorn, and too many others to list here. In the past few years, Henry has also held a number of residencies and offered workshops and master classes on major campuses, including: Berklee College of Music (Boston); Buffalo Academy for Visual & Performing Arts (upstate New York); CalArts, hosted by Wadada Leo Smith (Valencia, California); the Carlucci School, with Andrew Lamb and Newman Taylor Baker (Portugal); Hamilton College of Performing Arts, with Rashied Ali (upstate New York); Humber College (Toronto); JazzInstitut Darmstadt (Germany); Mills College, hosted by Roscoe Mitchell (Oakland, California); New England Conservatory (Boston, Massachusetts); Scuole Bruscio and Scuole Poschiavo (Switzerland); the University of Gloucestershire at Cheltenham (U.K.); University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois; University of Michigan at Ann Arbor; and several more. Henry can be heard on about a dozen new recordings, made his professional debut on a second instrument (the violin) at the age of 70 alongside Cecil Taylor at Lincoln Center, has seen the publication of the first volume of his poetry, "Signs Along the Road," by a publisher in Cologne, and creates illustrations to accompany his new recordings and publications. He has received many honors in recent years, including four Meet the Composer grants. Mr. Grimes can be heard on 90+ recordings on various labels, including Atlantic, Ayler Records, Blue Note, Columbia, ESP-Disk, ILK Music, Impulse!, JazzNewYork Productions, Pi Recordings, Porter Records, Prestige, Riverside, and Verve. He is the subject of a new biography published in London, "Music to Silence to Music: A Biography of Henry Grimes" by Dr. Barbara Frenz, with a beautiful foreword by Sonny Rollins (http://tinyurl.com/h9f8mo4). And on July 7th, 2016, Henry received a Lifetime Achievement Award and played a full evening of concerts with groups of his own choosing in the Arts for Art / Vision Festival at Judson Memorial Church in New York City , where he had also played and recorded with Albert Ayler's group back in the '60s. Henry Grimes is now a permanent resident of New York City and welcomes students here." ^ Hide Bio for Henry Grimes • Show Bio for Bernt Rosengren "Bernt Rosengren (born 24 December 1937, in Stockholm) is a Swedish jazz tenor saxophonist. His recordings have earned him five Gyllene Skivan awards in Sweden. Rosengren first played professionally at age 19, as a member of the Jazz Club 57, and two years later in 1959 he played in the Newport Jazz Band. Roman Polanski's collaborator Krzysztof Komeda used Rosengren in the performance of his jazz score for Polanski's film Knife in the Water (1962). Rosengren recorded a string of critically acclaimed albums in the 1960s and 1970s, including Stockholm Dues (1965), Improvisations (1969), and Notes from Underground (1974). He played in a sextet led by George Russell in the 1960s in Europe. Later in the decade he moved from hard bop into post-bop experimentation, playing with Don Cherry; in the 1970s, as a member of Sevda led by trumpeter Muvaffak "Maffy" Falay, he began working with elements of Turkish and Middle Eastern music. He also formed his own big band in the 1970s. In the 1980s, Rosengren worked frequently with American Jazz musicians, including Doug Raney, George Russell, Don Cherry and Horace Parlan. Among his activities in the 1990s include an album of songs from Porgy & Bess. Chris Mosey, a jazz critic from AllAboutJazz, said in his review of Rosengren's album I'm Flying (2009): "All in all, I'm Flying is a worthy Golden Record." Jack Bowers, also writing for AllAboutJazz, wrote in his review of the same album: "Rosengren, for his part, is a model of elegance and consistency, inspiring his companions without stealing their thunder. Together they comprise a tight-knit and consistently engaging foursome. Besides blowing superbly, Rosengren wrote seven of the album's twelve selections. - Rosengren rides their talents like an Indy car driver, and the result is an exemplary team effort that is as stylish as it is rewarding." ^ Hide Bio for Bernt Rosengren • Show Bio for Albert Mangelsdorff "Albert Mangelsdorff (September 5, 1928 in Frankfurt, Germany - July 25, 2005 in Frankfurt) was one of the most accredited and innovative trombonists of modern jazz who became famous for his use of multiphonics.[1] Mangelsdorff was born in Frankfurt. He was given violin lessons as a child and was self-taught on guitar in addition to knowing trombone. His brother, alto saxophonist Emil Mangelsdorff, introduced him to jazz during the Nazi period (a time when it was forbidden in Germany). After the war Mangelsdorff worked as a guitarist and took up trombone in 1948. n the 1950s Mangelsdorff played with the bands of Joe Klimm (1950-53), Hans Koller (1953-54) (featuring Attila Zoller), Jutta Hipp (1954-55), as well as with the Frankfurt All Stars (1955-56). In 1957 he led a hard bop quintet together with Joki Freund which was the nucleus of the Jazz-Ensemble of Hessian Broadcasting (with Mangelsdorff as its musical director until 2005). In 1958 he represented Germany in the International Youth Band appearing at the Newport Jazz Festival. In 1961 he recorded with the European All Stars (further recording in 1969). In the same year he formed a quintet with the saxophonists Heinz Sauer, Günter Kronberg, and bassist Günter Lenz and drummer Ralf Hübner which became one of the most celebrated European bands of the 1960s. In 1962 he also recorded with John Lewis ("Animal Dance"). After touring Asia on behalf of the Goethe-Institut in 1964 his quintet recorded the album "Now Jazz Ramwong" later that year which made use of Eastern themes. He also toured the USA and South America with the quintet. After Mangelsdorff's involvement in the European free jazz movement Kronberg left and the quartet remained (1969-71). During the early seventies the quartet was revived with Sauer, Buschi Niebergall and Peter Giger (1973-76). At the same time Mangelsdorff was exploring the new idiom with Globe Unity Orchestra, but also with many other groups (e.g. the trio of Peter Brötzmann). At that time, thanks to Paul Rutherford, he discovered multiphonics, long solistic playing and experimental sounds. He performed as unaccompanied trombonist in an impressive concert set. In the 1970s he made first solo recordings and collaborated with Elvin Jones (1975, 1978), Jaco Pastorius and Alphonse Mouzon (1976), John Surman, Barre Phillips and Stu Martin (1977) and others. In 1975 he was co-founder of the United Jazz and Rock Ensemble that existed for more than 30 years, and recorded duo albums with Wolfgang Dauner (from 1981). In 1976 Mangelsdorff started teaching jazz improvisation and style at Dr. Hoch's Konservatorium in Frankfurt. In the 1980s and 1990s Mangelsdorff continued to perform in solo and small settings, also playing with the Reto Weber Percussion Ensemble and Chico Freeman. Together with French bassist Jean-François Jenny Clark he founded the German-French jazz ensemble. In the 1990s he was also touring and recording with pianist Eric Watson, bass player John Lindberg and drummer Ed Thigpen and a second quartet with Swiss musicians and Dutch cellist Ernst Reijseger. In 1995 he replaced George Gruntz as musical director for the JazzFest Berlin. Since 1994 the Union of German Jazz-Musicians awards a regular prize in Mangelsdorff's honor, the Albert-Mangelsdorff-Preis. In 2007 the album Folk Mond & Flower Dream was re-released on CD. This album, produced by Horst Lippmann in 1967, was the last recording of the Albert Mangelsdorff Quintett. For more than twenty years the original master tapes of the recording seemed to be lost until they were found in spring 2007 in the archives of Horst Lippmann." ^ Hide Bio for Albert Mangelsdorff • Show Bio for Karl Berger "Karl Berger is a six time winner of the Downbeat Critics Poll as a jazz soloist, recipient of numerous Composition Awards ( commissions by the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, European Radio and Television: WDR, NDR, SWF, Radio France, Rai Italy. SWF-Prize 1994 ). Professor of Composition, Artist-in-Residence at universities, schools and festivals worldwide; PhD in Music Esthetics. Karl Berger became noted for his innovative arrangements for recordings by Jeff Buckley ("Grace"), Natalie Merchant ("Ophelia"), Better Than Ezra, The Cardigans, Jonatha Brooke, Buckethead, Bootsie Collins, The Swans, Sly + Robbie, Angelique Kidjo a.o.; and for his collaborations with producers Bill Laswell, Alan Douglas ("Operazone"), Peter Collins, Andy Wallace, Craig Street, Alain Mallet, Malcolm Burn, Bob Marlett a.m.o. in Woodstock, NY. New York City, Los Angeles, Tokyo, London, Paris, Rome. He recorded and performed with Don Cherry, Lee Konitz, John McLaughlin, Gunther Schuller, the Mingus Epitaph Orchestra, Dave Brubeck, Ingrid Sertso, Dave Holland, Ed Blackwell, Ray Anderson, Carlos Ward, Pharoah Sanders, Blood Ulmer, Hozan Yamamoto and many others at festivals and concerts in the US, Canada, Europe, Africa, India, Phillippines, Japan, Mexico, Brazil. His recordings and arrangements appear on the Atlantic, Axiom, Black Saint, Blue Note, Capitol, CBS, Columbia Double Moon, Douglas Music, Elektra , EMI, Enja, Island, JVC, Knitting Factory, In&Out, MCA, Milestone, Polygram, Pye , RCA, SONY, Stockholm, Vogue a.o. Founder and director of the Creative Music Foundation, Inc., dba The Creative Music Studio, a not-for-profit corporation, dedicated to the research of the power of music and sound and the elements common to all of the world's music forms; and to educational presentations through workshops, concerts, recordings, with a growing network of artists and CMS members worldwide.Conducted CMS Residencies worldwide. In the 90s, Dr. Berger was Professor of Composition and Dean of Music Education at the Hochschule fuer Musik, Frankfurt / Germany. Chairman of the Music Department at UMass Dartmouth till 2006.Now re-establishing CMS programming in collaboration with producer Rob Saffer, directing the CMS Archive Project, recording and producing. Performing internationally with the Allstar Ensemble "In the Spirit of Don Cherry" and with numerous projects, collaborating with vocalist/poet Ingrid Sertso ( contact CreativeMusicAgency@gmail.com ). Recording a Trlogy of Piano Music for Tzadik Records. Collaborating with bassist Ken Filiano, vocalist Ingrid Sertso (KIK) + guitarist Kenny Wessel (KIKK). The Karl Berger Improvisers Orchestra, completed 75 performances in New York since the Spring of 2011 (see BLOG at www.karlberger.org). New collaboration in Europe with drummer Baby Sommer, bassist Antonio Borghini, guitarist Carsten Radtke, vocalist/poet Ingrid Sertso (DIFFERENT STANDARDS). Collaborating with cornetist Ken Knuffke, violinist Jason Hwang, saxophonists Ivo Perelman, Peter Apfelbaum, Mercedes Figueras, drummers Harvey Sorgen, Tani Tabbal, Warren Smith, Tyshawn Sorey. bassists Joe Fonda, Mark Helias, Max Johnson, William Parker, trumpeter Steven Bernstein and others for recordings and performances." ^ Hide Bio for Karl Berger • Show Bio for Sonny Sharrock "Warren Harding "Sonny" Sharrock (August 27, 1940 - May 25, 1994) was an American jazz guitarist. He was married to singer Linda Sharrock, with whom he recorded and performed. One of only a few prominent guitarists who participated in the first wave of free jazz during the 1960s, Sharrock was known for his heavily chorded attack, highly amplified bursts of feedback, and use of aggressive sustain to achieve saxophone-like lines on guitar. His early work also features creative use of a slide. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Sonny Sharrock • Show Bio for Arild Andersen "Born in Norway October 27 -1945 . He has been one of Europe's leading bass player for more than 30 years. Andersen started out as a member of Jan Garbarek Quartet(67-73) . The group also included Terje Rypdal and Jon Christensen.In the same period he also worked with Norwegian singer Karin Krog and played in the rhythm section for visiting American musicians such as; Phil Woods, Dexter Gordon, Hampton Hawes, Johnny Griffin, Sonny Rollins, and Chick Corea. He also worked with Don Cherry and George Russell in this years. In 1972-74 he visited New York several times and worked with Stan Getz Quartet, Sam Rivers trio, Sheila Jordan, Steve Kuhn and Paul Bley. In 1974 Arild Andersen formed his own quartet. The band toured Scandinavia and Europe and recorded 3 albums for ECM with this band. He also had a band together with singer Radka Toneff in the late 70-ties and early 80-ties. In1980 Arild Andersen put together a band that included Kenny Wheeler,Paul Motian,and Steve Dobrogosz(Lifelines-ECM). In -81 he had a band with Alphonse Mouzon, Bill Frisell and John Taylor (A Molde Concert ,ECM). This band also toured Europe in -83, this time with John Abercrombie on guitar. 1982 he formed "The Arild Andersen Quintet" with Jon Christensen dr. Jon Balke p, Tore Brunborg sax, Nils Petter Molvær tp. The band changed name later to "Masqualero". This band was in the forefront of European jazz for 10 years ,the last years as quartet without piano. Masqualero toured USA, Canada, East and West Europe and made four albums ,one for the Norwegian label "Odin " and three for ECM. Three of the albums won the Norwegian "Grammy"award. Arild Andersen released in 1993 a trio recording with Ralph Towner and Nana Vasconcelos,"If You Look Far Enough" on ECM. Over the last years Arild Andersen has also spent time investing the possibility of combining traditional Norwegian folk music with improvised music. He started in 1988 a collaboration with singer Kirsten Braaten Berg, one of the leading artists in Norwegian folk music. This lead to the successful work "Sagn" premiered in -90 and performed more than 40 times including Town Hall, New York, Germany and Scandinavia. "Sagn" was recorded -91 on The Norwegian label "Kirkelig Kulturverksted" and later released on ECM. In 93 he premiered a new work called "Arv", also recorded on Kirkelig Kulturverksted. In 1994 he wrote music for a theatre version on the Nobel prized trilogy "Kristin Lavransdatter" by Sigrid Undset. This also lead to several performances of the concert version of the music and a recording for Kirkelig Kulturverksted. Arild Andersens work " Hyperborean" , commissioned by " The Molde International Jazz festival" premiered in 95 .This was a 9-piece band including the Norwegian string quartet Cikada. The music was recorded in October-96 and was released in September 1997 by ECM. 1998 he formed a trio together with German trumpeter Markus Stockhausen and French percussion-player Patrice Heral. This trio+ Terje Rypdal as a guest, made a CD called "Karta", released sept 2000 by ECM. 1999 Andersen started a trio with English drummer John Marshall and the Greek piano player Vassilis Tsabroupolos. They released two cd's on ECM, Achirana 2000 and The Triangle 2004. In 2001 he played concerts at The Molde International Jazz Festival with Pat Metheney who was "Artist in Recidence" and Norwegian drummer Paal Nilsen-Love. June 2002 he premiered the music to Sophocles Greek Drama " Electra " at the Herodes Theater in Athens. This performance was a part of the Athens Olympic Games cultural issue. The cd of the music was released as "Electra" by ECM 2005 . In 2004 he started a colaboration with Hungarian Gutarist Ference Snetberger which led to a Quartet recording "Joyosa" 2004 and a Trio Recording "Nomad" 2005. In 2002 he became a member of the Dahl/Andersen/Heral trio which recorde two cd's for Stunt records in Denmark . "The Sign" and "Moonwater". In 2005 Arild Andersen was "Artist in Residence" at The Molde Jazz festical with 5 concerts during the week including one Soloconcert, Electra, Snetberger trio and a special project with Kudsi Ergunner and Nana Vasconcelos. In 2005 he also wrote a commission work for a duo with Saxophonist Tommy Smith. This was called " Independency " and led to the formation of his new trio with Paolo Vinaccia on drums and Tommy Smith on saxophone. This trio made a live recording at the club Belleville in Oslo autumn 2007. It was released 2008 on ECM " Live at Belleville ". It got raving reviews around the world and this trio is Arild Andersens main project these days with concerts around the world. Arild Andersen received " Prix du Musicien Européen" 2008 from the "Academie du Jazz " in France. In 2010 he visited Japan for the first time and his trio was claimed by the Japan press to be the highlight of the "Tokyo International Jazzfestival 2010". In october 2010 he did four concerts with Scottish National Jazz Orchestra under direction of Tommy Smith . The music was a celebration of ECM with songs recorded on the lable over the years like Keith Jarrett´s My Song, Chick Corea´s Crystal Silence , Dave Holland´s May Dance and more . The Glasgow concert was released on ECM spring 2012 called " Celebration" . January 2014 he released "MIRA" on ECM a new cd with his trio with Paolo Vinaccia and Tommy Smith March 2018 he released a Live trio recording in Austria " In House Science" on ECM." ^ Hide Bio for Arild Andersen • Show Bio for Jacques Thollot "Jacques Thollot, drummer, keyboardist and composer, prodigy pupil of bebop drummer Kenny Clarke, appeared very young on the jazz scene with Sidney Bechet. Performing regularly in the 1960s in Parisian clubs, he became a very popular accompaniment of avant-garde musicians as important as Eric Dolphy, Don Cherry, Barney Wilen, Rene Thomas or Joachim Kühn, and all the adventurous French musicians of this time. With this legendary solo album nicknamed "The Giraffe" dated 1971, Jacques Thollot, who plays various instruments and innovates in France in the use of multitrack and sound effects in the studio, becomes an icon with all worlds of underground music and free rock from around the world." ^ Hide Bio for Jacques Thollot

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

7/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Awake Nu 6:55

2. Taste Maker 6:49

3. The Thing 5:51

4. There Is the Bomb 4:51

5. Unite 17:14

6. Eternal Rhythm 18:01

7. Eternal Rhythm II 20:10

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Free Improvisation

Quartet Recordings

Large Ensembles

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

European Improvisation, Composition and Experimental Forms

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Jazz Reissues

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![BlueRing Improvisers: Materia [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36513.jpg)

![Wheelhouse (Rempis / Adasiewicz / McBride): House And Home [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36462.jpg)

![+DOG+: The Light Of Our Lives [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36009.jpg)

![Parker, Evan / Jean-Marc Foussat: Insolence [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36398.jpg)

![Deupree, Jerome / Sylvie Courvoisier / Lester St. Louis / Joe Morris: Canyon [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36404.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)