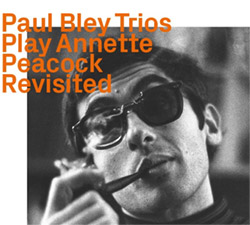

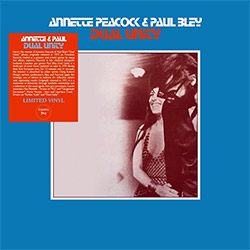

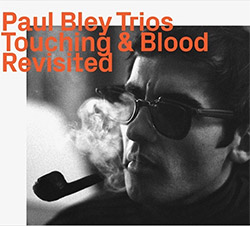

Annette Peacock's response to the free-blowing loft scene was to compose using spacious intervals, allowing great harmonic and rhythmic freedom, inspiring pianist Paul Bley and his trio as heard in two unique interpretations of the same pieces from two exceptional working bands: one with bassist & drummer Mark Levinson & Barry Altschul, the other with Gary Peacock & Billy Elgart.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Paul Bley-piano

Mark Levinson-double bass

Barry Altschul-drums

Gary Peacock-double bass

Billy Elgart-drums

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156114222

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1142

Squidco Product Code: 32591

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2022

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Tracks 1-3 recorded in Rome, Italy, on July 1st, 1966.

Tracks 4-8 recorded in Baarn, The Netherlands, on September 21st, and October 4th, 1966.

Tracks 9-14 recorded in Seattle, Washing, on May 10th and 12th, 1968.

"Those who play piano exceptionally well, or in a notably creative way, typically fall into one of several categories. There is the pianist as composer, the pianist as interpreter, the pianist as virtuoso. Of course, the roles are not exclusive and sometimes overlap. But in his career as a jazz pianist, Paul Bley created his own niche, the pianist as conceptualist; that is, he saw the necessity of change - adaptation and expansion - in the evolution of jazz through stylistic periods, and devoted his most innovative period, roughly the late '50s to the early '70s, to devising musical strategies that would expand its formal and expressive qualities. It was a subject he spoke of often, as he chronicled the early experiences which put him on this path, beginning with his meeting Ornette Coleman in 1958.

Although he had envisioned and experimented with "free" playing prior to this, performing with Ornette, Don Cherry, and Charlie Haden at the Hillcrest Club in Los Angeles provided him with the impetus to pursue this then-radical perspective as the focus of his career. Each of his subsequent experiences broadened the conceptual possibilities of "free jazz" both as a soloist and in the ensemble. Recording and touring with the Jimmy Giuffre Trio in 1961 initiated the separation of group members into freely functioning agents choosing their own pulse and phrasing. Spending 1963 on the road with Sonny Rollins introduced stretching songs into marathons of free-associative improvisation. New York City in 1964 produced the Jazz Composers Guild, and local gigs with extreme saxophonists Albert Ayler and John Gilmore, inspired by the unorthodox compositions of Carla Bley, evoked freedom in the music's furthest parameters.

By 1965, Bley had settled on the trio format, and touring Europe revealed a warmer reception for music that employed chordless improvisations, three-way rhythmic counterpoint, unfamiliar melodic constructs, and malleable song form. (The first such documented was Touching, revisited on ezz-thetics 1108). The group's bassist had shifted according to availability, from Gary Peacock to Steve Swallow to Kent Carter. The next year Mark Levinson joined Bley and percussionist Barry Altschul for their European sojourn, which bring us to the first half of the music at hand. But there was an equally momentous conceptual change in the group's material, as the adventurous pieces by Carla Bley were gradually being replaced by those of Paul's new partner, Annette Peacock.

The contrast in material from these two remarkable composers symbolized the pianist's desire to push into uncharted territories. While Carla's early, intricate pieces were frequently designed to fit the possibilities of specific musicians working on divergent paths to freedom, Peacock's songs precariously balanced states of intense emotion and intuitive development. She explained her structural qualities of stark intervals and sparse rhythms in a 2014 interview with The Quietus: "When I came back to New York at the time I started my career - if you can call it that - in the world of avant-garde jazz, everything had broken loose. Everyone was blowing, improvising together simultaneously in the lofts. It was totally free. It was an aggressively masculine texture assaulting you. I'm not male and I wasn't involved in it so I could see it from an objective perspective. And it seemed like I had to carve space out ... to slow things down. So I started writing ballads, with two notes basically, just intervals. No chords. Very minimal. Musicians had no idea what to play on it. I felt at the time my responsibility was to create environments that improvising musicians could perpetuate; [they needed] to create an architecture basically."

At the same time, it should not be ignored that many if not all of these "ballads" were composed as, in her words, "free form songs," with lyrics that expressed feelings of loss, psychic pain, alienation. The lyrics of "Nothing Ever Was, Anyway" are, in part, "Soon I will die and everything will fade away, / Nothing ever was, anyway. / Hold yourself to keep from going mad." "Blood" featured equally powerful sentiments, "Send me none of your promises / keeping the sorrow. / Hold it tighter tomorrow, / you'll be out for blood." Thus, her titles reveal significant meanings, and the combination of such existential anxiety and near-complete harmonic and rhythmic freedom, requiring a structure to be imposed upon personal experience, no doubt inspired Bley to his most dramatic and imaginative improvisations - such as the exquisitely poignant "Touching," a title which on its own reflects upon the simplest and most profound of gestures.

Between 1966 and 1968 - the second half of this program - Bley's next conceptual step was to extend the so-called "classic Bill Evans trio format," via Peacock's elliptical arias, into long form spatial suspension of time and motion, equally divided among piano, bass, and drums. (One example, "Blood," may be heard on the above cited ezz-thetics release.) But the opportunity to reunite with bassist Gary Peacock, and the addition of drummer Billy Elgart, gave him the opportunity to re-examine the songs from another, compact, intimate perspective. This proved to be a temporary readjustment, however, as the next great conceptual leap was the Bley-Peacock Synthesizer Show, which would take them into the next decade."-Art Lange, Chicago, October 2022

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Paul Bley "Hyman Paul Bley, CM (November 10, 1932 - January 3, 2016) was a Canadian pianist known for his contributions to the free jazz movement of the 1960s as well as his innovations and influence on trio playing and his early live performance on the Moog and Arp audio synthesizers. Bley was a long-time resident of the United States. His music has been described by Ben Ratliff of the New York Times as "deeply original and aesthetically aggressive." Bley's prolific output includes influential recordings from the 1950s through to his solo piano records of the 2000s. Bley was born in Montreal, Quebec, on November 10, 1932. His adoptive parents were Betty Marcovitch, an immigrant from Romania, and Joe Bley, owner of an embroidery factory. However, in 1993 a relative from the New York branch of the Bley family walked into Sweet Basil in NYC and informed him that his father was actually his biological parent. At age five Bley studied violin, but at age seven he decided to switch to the piano. By eleven he received a junior diploma from the McGill Conservatory in Montreal. At thirteen he formed a band which played at summer resorts in Ste. Agathe, Quebec. As a teenager he played with touring American bands, including Al Cowan's Tramp Band. In 1949, when Bley was starting his senior year of high school, Oscar Peterson asked Bley to fulfill his contract at the Alberta Lounge in Montreal. The next year Bley left Montreal for New York City and Julliard. In the 1951, on a return trip to Montreal, Bley organized the Jazz Workshop with a group of Montreal musicians. In 1953 Bley invited the bebop alto saxophonist and composer Charlie Parker to the Jazz Workshop, where he played and recorded with him. When Bley returned to New York City he hired Jackie McLean, Al Levitt and Doug Watkins to play an extended gig at the Copa City on Long Island. In 1953 the Shaw Agency booked Bley and his trio to tour with Lester Young, billed as "Lester Young and the Paul Bley Trio" in ads. He also performed with tenor saxophonist Ben Webster at that time. He then conducted for bassist Charles Mingus on the Charles Mingus and His Orchestra album. Additionally, in 1953, Mingus produced the Introducing Paul Bley album for his label, Debut Records with Mingus on bass and drummer Art Blakey . (In 1960 Bley recorded again with the Charles Mingus Group.) In 1954 Bley received a call from Chet Baker inviting him to play opposite Baker's quintet at Jazz City in Hollywood, California for the month of March. This was followed by a tour with singer Dakota Staton. Down Beat Magazine interviewed Bley for its July 13, 1955 issue. The prescient title of the article read, "PAUL BLEY, Jazz Is Just About Ready For Another Revolution." The article, reprinted in Down Beat's 50th Anniversary edition, quoted Bley as saying, "I'd like to write longer forms, I'd like to write music without a chordal center." Bley's trio with Hal Gaylor and Lennie McBrowne toured across the US in 1956, including a club in Juarez. Mexico. The tour culminated with an invitation to play a 1956 New Year's Eve gig at Lucile Ball and Desi Arnez's home in Palm Springs. During the evening, Bley collapsed on the bandstand with a bleeding ulcer and Lucy immediately took him to the Palm Springs hospital where she proceeded to pay for all of his medical care. Bley, who had met Karen Borg while she was working as a cigarette girl at Birdland in NYC, married her after she came out to meet him in Los Angeles, where she became Carla Bley. In 1957 Bley stayed in Los Angeles where he had the house band at the Hillcrest Club. By 1958 the original band, with vibe player, Dave Pike, evolved into a quintet with Bley hiring young avant garde musicians trumpet player Don Cherry, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins. In the early 1960s Bley was part of "The Jimmy Giuffre 3," with Giuffre on reeds, and Steve Swallow on bass. Its repertoire included compositions by Giuffre, Bley and his now ex-wife, composer Carla Bley. The group's music moved towards chamber jazz and free jazz. The 1961 European tour of The Giuffre 3 shocked a public expecting Bebop, however the many recordings released from this tour have proven to be classics of free jazz. During the same period, Bley was touring and recording with tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins, which culminated with the RCA Victor album Sonny Meets Hawk! with tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. Bley's solo on "All The Things You Are" from this album has been called "the shot heard around the world" by Pat Metheny. In 1964 Bley was instrumental in the formation of the Jazz Composers Guild, a co-operative organization which brought together many free jazz musicians in New York: Roswell Rudd, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, Carla Bley, Michael Mantler, Sun Ra, and others. The guild organized weekly concerts and created a forum for the "October Revolution" of 1964. In the late 1960s, Bley pioneered the use of the Arp and Moog synthesizers, performing live before an audience for the first time at Philharmonic Hall in New York City on December 26, 1969. This "Bley-Peacock Synthesizer Show" performance, a group with singer/composer Annette Peacock, who had written much of his personal repertoire since 1964, was followed by her playing on the recordings Dual Unity (credited to "Annette & Paul Bley") and Improvisie. The latter was a French release of two extended improvisational tracks with Bley on synthesizers, Peacock's voice and keyboards, and percussion by Dutch free jazz drummer Han Bennink, who had also appeared on part of Dual Unity. [biography continues...]" ^ Hide Bio for Paul Bley • Show Bio for Mark Levinson "Mark Levinson (born December 11, 1946) is an American audio equipment designer, recording and mastering engineer, multi-instrumentalist musician, and serial entrepreneur. He was formerly married to the actress Kim Cattrall. Mark Levinson worked as the bassist for five years (1966Ð1971) for jazz pianist Paul Bley and played with other renowned jazz musicians of the period. In 1972, Levinson founded Mark Levinson Audio Systems (MLAS, Ltd.) in New Haven, Connecticut. He ran MLAS from 1972 to 1980, during which time he created products such as the LNP-2 preamplifier. He also invented the concept of high-end car sound in 1979.[citation needed] However, by 1980 MLAS was in financial trouble. Levinson then asked Sanford Berlin, a retired executive in the audio industry, to invest in MLAS and to aid in the management of the company. Berlin personally invested $480,000 in the company and persuaded several others to invest an additional $300,000. In the summer of 1984 Levinson left MLAS and founded another company to produce audio equipment, Cello Ltd. Levinson became president and one of the three directors of Cello. MLAS launched a lawsuit attempting to prevent Levinson from working in the audio industry for the rest of his life, on the grounds that he was a "walking trade name" who could "diminish the value of their asset." Levinson won the case in 1986 but lost the right to use his name as a trade name on an audio product. For this reason, since several years before the lawsuit, "Mark Levinson" branded audio products have had no relationship to the brand's founder; the "Mark Levinson" brand name has been and continues to be an intellectual property wholly owned by Harman International. In resolving the case, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals wrote a 25-page decision that outlined the rights of entrepreneurs who use their own name as the name of a company.[citation needed] Levinson himself has continued to work in the industry, creating several new companies. Levinson ran his second company, Cello Ltd., from 1984 to 1998. With Cello, Levinson created high-priced models such as the Audio Palette.[citation needed] In 1999, Levinson founded Red Rose Music, an audio company with its own New York retail store on Madison Avenue. The business model of Red Rose was to create compact, affordable products with very high-quality sound.[citation needed] In 2007, Levinson moved to Switzerland and used his consulting revenue to finance the founding of Daniel Hertz S.A., a high-performance audio equipment and audio software company with a holistic approach, that considers the quality of recordings an important part of the playback system. Mark Levinson and the actress Kim Cattrall were married from 1998 to 2004. The couple co-wrote the book Satisfaction: The Art of the Female Orgasm (2002)." ^ Hide Bio for Mark Levinson • Show Bio for Barry Altschul "Barry Altschul (born January 6, 1943, New York City)[1] is a free jazz and hard bop drummer who gained fame in the late 1960s with the pianists Paul Bley and Chick Corea. Altschul, having initially taught himself to play drums, studied with Charlie Persip during the 1960s. In the latter part of the decade, he performed with Paul Bley. In 1969 he joined with Chick Corea, Dave Holland and Anthony Braxton to form the group Circle. At the time, he made use of a high-pitched Gretsch kit with add-on drums and percussion instruments, which he integrated seamlessly in a whirlwind of sound. In the 1970s Altschul worked extensively with Anthony Braxton's quartet featuring Kenny Wheeler, Dave Holland, and George Lewis. Braxton, signed to Arista Records, was able to secure a large enough budget to tour with a collection of dozens of percussion instruments, strings and winds. In addition to his participation in ensembles featuring avant-garde musicians, Altschul performed with Lee Konitz, Art Pepper and other "straight ahead" jazz performers. Altschul also made albums as a leader, but after the mid-1980s he was rarely seen in concert or on record, spending much of his time in Europe. Since the 2000s, he has become more visible, with two sideman appearances on the CIMP label with the FAB trio (with Billy Bang and Joe Fonda), the Jon Irabagon Trio recording "Foxy", and the bassist Adam Lane. Altschul has played or recorded with many musicians, including Roswell Rudd, Dave Liebman, Barre Phillips, Denis Levaillant, Andrew Hill, Sonny Criss, Hampton Hawes, and Lee Konitz."-Wikipedia ^ Hide Bio for Barry Altschul • Show Bio for Gary Peacock "Gary Peacock (born May 12, 1935, in Burley, Idaho, United States) is an American jazz double-bassist. After military service in Germany, in the early sixties he worked on the west coast with Barney Kessel, Bud Shank, Paul Bley and Art Pepper, then moved to New York. He worked there with Bley, the Bill Evans Trio (with Paul Motian), and Albert Ayler's trio with Sunny Murray. There were also some live dates with Miles Davis, as a temporary substitute for Ron Carter. Peacock spent time in Japan in the late 1960s, abandoning music temporarily and studying Zen philosophy. After returning to the United States in 1972, he studied Biology at the University of Washington in Seattle, and taught music theory at Cornish College of the Arts from 1976 to 1983. In 1983 he joined Keith Jarrett's "Standards Trio" with Jack DeJohnette (the three musicians had previously recorded Tales of Another in 1977 for ECM Records, under Peacock's leadership). Among the trio's albums are Standards, Vol. 1 and Standards, Vol. 2 and Standards Live. With the breakup of the "Standards Trio" in 2014, Peacock decided to continue his career as the leader of his own piano trio, with Marc Copland on piano and Joey Baron on drums. His 80th birthday year (2015) saw him touring worldwide with this trio to support their ECM release." ^ Hide Bio for Gary Peacock

6/25/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/25/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/25/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

6/25/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Both 9:31

2. Albert's Love Theme 9:23

3. Touching 7:32

4. Blood 4:27

5. El Cordobes 3:50

6. Nothing Ever Was, Anyway 5:49

7. Mister Joy 5:24

8. Kid Dynamite 2:58

9. Nothing Ever Was, Anyway 5:37

10. El Cordobes 6:13

11. Kid Dynamite 3:14

12. Touching 4:53

13. Blood 6:12

14. Mister Joy 4:01

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Free Improvisation

Jazz

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Trio Recordings

Piano Trio (Piano Bass Drums)

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

New in Improvised Music

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Haarvol: The Subliminal Paths [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36232.jpg)

![Eventless Plot | Francesco Covarino: Methexis [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36231.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Das B (Mazen Kerbaj / Mike Majkowski / Magda Mayas / Tony Buck): Love [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36329.jpg)

![Hemphill Stringtet, The: Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36409.jpg)

![Halvorson, Mary Septet: Illusionary Sea [2 LPS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17952.jpg)

![Re-Ghoster Extended: The Zebra Paradox [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36204.jpg)

![FDF Trio: Possibility And Prejudices From Within A Cup [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36205.jpg)

![Money : Money 2 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35894.jpg)

![Klinga, Erik: Elusive Shimmer [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36258.jpg)

![CHANGES TO blind (Phil Zampino): Volume 9 - I Wave on a Fine Vile Mist [CD + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36061.jpg)

![Wallmart / Rubbish: Asset Protection [split CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35900.jpg)

![+Dog+: The Family Music Book Vol. 5 [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35897.jpg)

![Kuvveti, Deli : Kuslar Soyledi [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36107.jpg)

![Nakayama, Tetsuya: Edo Wan [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36105.jpg)

![Yiyuan, Liang / Li Daiguo: Sonic Talismans [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35957.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36206.jpg)

![Palestine, Charlemagne / Seppe Gebruers: Beyondddddd The Notessssss [NEON GREEN VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36207.jpg)

![Laubrock, Ingrid: Purposing The Air [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35639.jpg)

![Yoko, Ono / The Great Learning Orchestra: Selected Recordings From Grapefruit [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35841.jpg)

![Zorn, John / JACK Quartet: The Complete String Quartets [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35609.jpg)

![Lonsdale, Eden: Dawnings [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35480.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)