If you were asked by Oscar Peterson to sub for him, or you played with the likes of Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, and Coleman Hawkins, and had Charles Mingus produce your first album, you must have been doing something right. This was the case for Montreal-born pianist Paul Bley, who certainly had mastered the craft of song interpretation and jazz improvisation early in his career and developed his own voice in the process. So the next thing was to take the music somewhere else. Famously, this is what he wanted to do, as he expressed in the Downbeat article (July 13, 1955), "PAUL BLEY, Jazz Is Just About Ready For Another Revolution," in which he was quoted as saying "I'd like to write longer forms, I'd like to write music without a chordal center." This is the kind of thing Bley went on to do over a prolific career until his death in 2016.

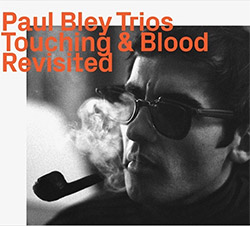

To revisit the Bley output is to observe the evolution of his distinct and distinguished envelope-pushing approach. This recent Hat Hut reissue of early trio recordings (the full Touching album from 1965 and the title track of Blood from 1966) provide an excellent glimpse into the aesthetic at work that earned Bley so much respect and which inspired others to follow the free jazz piper.

One of many notable features of Bley's early music is the peculiarity of his own compositions, but also his use of pieces by Annette Peacock and Carla Bley. The compositions were no doubt instrumental in fashioning the Bley trio sound which is characterized on these recordings by the use of space, timbral coloring and gradations of dynamics, rather than straight-ahead rhythm playing in the tradition of swing and post-swing idioms. Along for the ride for the first seven tracks are Kent Carter on double bass and Barry Altschul on drums, and on the final track ("Blood") Carter is replaced by Mark Levinson. The first session was recorded in Copenhagen, the second in Haarlem the Netherlands. Both are robust sessions of creative playing that colors outside the lines of jazz parameters common at the time, allowing for ingenious individual expression outside post-bop orthodoxy.

The first five tracks contain lots of stops and starts and exploration of the melodic, harmonic and rhythmical material in a very free and unconventional manner. Track six, "Both," has a hard-bop flourish to it, but is reminiscent of another great iconoclastic pianist from the same generation, Cecil Taylor, in its heavy percussive reiterations of motif and its use of the piano's extended range and dynamics. Bley, like Taylor, stands as one of the pillars of post-modern jazz who merits a re-listen now and then, and this release provides a fitting occasion to indulge.

Comments and Feedback:

More Recent Reviews, Articles, and Interviews @ The Squid's Ear...

|