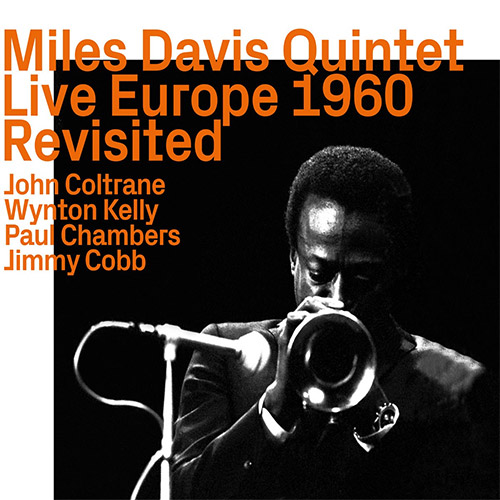

Culled from two concerts on Norman Granz's Spring 1960 European tour, Miles' seminal 50s band was on the point of dissolution, Coltrane soon to leave to form his own classic quartet, and the distinction between the old and new is evident in Coltrane's expansive and intricate soloing over standards and Kind of Blue material including "So What" or "On Green Dolphin Street".

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 2.00 units

Sample The Album:

Miles Davis-trumpet

John Coltrane-tenor saxophone

Wynton Kelly-piano

Paul Chambers-double bass

Jimmy Cobb-drums

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156113522

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1135

Squidco Product Code: 32214

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2022

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Tracks 1 and 3 recorded at Olympia, in Paris, France, on May 21st, 1960; tracks 4 and 5 recorded at Konsert-huset, in Stockholm, Sweden, on March 22nd, 1960.

"The Miles Davis Quintet of early 1960 was an endangered, embattled entity. Davis and his frontline foil John Coltrane had been drifting apart stylistically and temperamentally for months. United in the embrace and exploration of modal devices on the trumpeter's seminal Kind of Blue album released the previous summer, bandleader and sideman were increasingly at odds as to where to go next with the celebrated innovations.

Davis, ever the savvy performer, viewed the advancements as part of the larger package of his ensemble's repertoire, a stockpile which also included fan-servicing interpretations of standards and chord-based originals from earlier editions of his songbook. Conversely, Coltrane had cottoned to them as a fresh conception point, integrating progressive lessons learned from Thelonious Monk, John Gilmore, and others to probe beyond the parameters of linear improvisation.

Davis' other sidemen found themselves caught in the middle of these competing priorities and directions. Pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb had been privy to Coltrane's developing blueprint four months earlier as participants in one of the saxophonist's Giant Steps sessions. Only a single piece from the convening, "Naima," made it on to the album, but as a collective they were versed in their colleague's germinating propensities.

Offered a headlining slot on producer Norman Granz's Spring 1960 European package tour, Davis conscripted a reluctant Coltrane after vibraphonist Buddy Montgomery bowed out of the prospective band. The saxophonist's reticence was conspicuous enough that Granz was compelled to sweeten the deal with additional funding. Coltrane acquiesced and rejoined the fold, but the quintet's initial concert in Paris made clear that musical capitulation was an arguable part of the arrangement at best.

Culled from three concerts on the tour, this survey captures the fomenting frictions in bold relief, beginning with a rendering of "So What" that surges beyond its Kind of Blue archetype and finds a solid opening solo by Davis made almost perfunctory by Coltrane's extended, ebullient effusiveness. Kelly balances the stark differences of his colleagues beautifully, laying out for sections during the fiery saxophone solo and letting Chambers and Cobb cover any lacunae in loose-limbed swing.

A similar divergence unfolds throughout "On Green Dolphin Street" with Coltrane following Davis' muted foray with a solo that starts balladic sweet, but soon trades for tart multiphonics. The rhythm section again works as flexible fencing, keeping form while also staying out of Coltrane's cutting, loquacious way. Kelly's extended solo, filled with dancing dexterity, resets the mood with a see-sawing bowed statement from Chambers priming a muted, Davis-led exit.

"Walkin'," from a second Parisian concert the same day, finds Davis slightly disheveled in the opening choruses but integrating expressive vocal effects into his ensuing solo. Coltrane's answer unfurls to nearly thrice the duration, steeped in a flinty cry and flanked by Cobb's choppy fills, Kelly's light commentary, and Chambers steady strolling bassline. Another textbook illustration of the divide between Davis and his errant employee. Kelly resumes a grand unifier role with an incandescent solo that swings on all cylinders, and Chambers presages the conclusion with another bold arco improvisation. Versions of "All Blues" and "So What" from the next day in Stockholm feature similar seasoning.

Audience reactions to the stage-telegraphed drama were analogously divided across tour stops, although judging from the often-audible and effusive applause interspersed on the recordings there were obviously droves in attendance who felt they got their monies worth. Both Davis and Coltrane would court controversy in the ensuing years, the former with frequent, calculated design. A minor, but vocal, critical contingent would even argue erroneously that Coltrane's contributions to Davis were undemocratic indulgences rather than early dispatches presaging the shape of jazz to come.

Davis, to his credit, never entertained the naysayers, and it's important to remember that a reciprocal and resilient respect pervaded between the occasionally chafed leader and wayward sideman. In his more churlish moments, Davis later downplayed or deflected the import of the relationship, suggesting that the decisions leading to the saxophonist's departure were purely strategic and professional. The immediate trajectories of the two men's careers in the aftermath of their dissolution tell a more complex story than the trumpeter's press-tailored testimonials. Each musician would continue to search for a congruous aggregation to serve as vessel for their evolving ideas.

Davis' investigative enterprise took longer, starting with the hiring of Sonny Stitt to occupy Coltrane's soon vacant seat on the tour. The expedient decision ended up an arguable unforced error in that Stitt's bop-favored style pulled the band backwards into a position of comparative familiarity and safety. A succession of contending saxophonists followed over the ensuing years, including Hank Mobley, George Coleman, and Sam Rivers. Culmination of Davis' search would eventually hinge on heeding the erstwhile advice Coltrane had offered in suggesting Wayne Shorter as his replacement, yielding an influential second Classic Quintet with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams.

Coltrane's quest was shorter as he methodically experimented with sidemen before conclusively assembling his Classic Quartet with McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, and Elvin Jones by early 1962. Both bandleaders would align with labels and producers that would accord them enviable latitude in documenting their respective musical metamorphoses. Davis, in confrere Teo Macero at Columbia, and Coltrane, in ardent advocate Bob Thiele at Impulse. With antecedents in the Davis quintet that preceded them, these two insurgent ensembles would alter and advance small-scale jazz immeasurably in their parallel wakes, auguring transformations to the idiom that reverberate with enduring authority today."-Derek Taylor, May 2022

The Squid's Ear!

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Miles Davis "Miles Davis, in full Miles Dewey Davis III, (born May 26, 1926, Alton, Illinois, U.S.-died September 28, 1991, Santa Monica, California), American jazz musician, a great trumpeter who as a bandleader and composer was one of the major influences on the art from the late 1940s. Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, where his father was a prosperous dental surgeon. (In later years he often spoke of his comfortable upbringing, sometimes to rebuke critics who assumed that a background of poverty and suffering was common to all great jazz artists.) He began studying trumpet in his early teens; fortuitously, in light of his later stylistic development, his first teacher advised him to play without vibrato. Davis played with jazz bands in the St. Louis area before moving to New York City in 1944 to study at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School)-although he skipped many classes and instead was schooled through jam sessions with masters such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Davis and Parker recorded together often during the years 1945-48. Davis's early playing was sometimes tentative and not always fully in tune, but his unique, intimate tone and his fertile musical imagination outweighed his technical shortcomings. By the early 1950s Davis had turned his limitations into considerable assets. Rather than emulate the busy, wailing style of such bebop pioneers as Gillespie, Davis explored the trumpet's middle register, experimenting with harmonies and rhythms and varying the phrasing of his improvisations. With the occasional exception of multinote flurries, his melodic style was direct and unornamented, based on quarter notes and rich with inflections. The deliberation, pacing, and lyricism in his improvisations are striking. [...]" ^ Hide Bio for Miles Davis • Show Bio for John Coltrane "John Coltrane, in full John William Coltrane, byname Trane, (born September 23, 1926, Hamlet, North Carolina, U.S.-died July 17, 1967, Huntington, New York), American jazz saxophonist, bandleader, and composer, an iconic figure of 20th-century jazz.John Coltrane, 1966. Coltrane's first musical influence was his father, a tailor and part-time musician. John studied clarinet and alto saxophone as a youth and then moved to Philadelphia in 1943 and continued his studies at the Ornstein School of Music and the Granoff Studios. He was drafted into the navy in 1945 and played alto sax with a navy band until 1946; he switched to tenor saxophone in 1947. During the late 1940s and early '50s, he played in nightclubs and on recordings with such musicians as Eddie ("Cleanhead") Vinson, Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges. Coltrane's first recorded solo can be heard on Gillespie's "We Love to Boogie" (1951). Coltrane came to prominence when he joined Miles Davis's quintet in 1955. His abuse of drugs and alcohol during this period led to unreliability, and Davis fired him in early 1957. He embarked on a six-month stint with Thelonious Monk and began to make recordings under his own name; each undertaking demonstrated a newfound level of technical discipline, as well as increased harmonic and rhythmic sophistication. During this period Coltrane developed what came to be known as his "sheets of sound" approach to improvisation, as described by poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka): "The notes that Trane was playing in the solo became more than just one note following another. The notes came so fast, and with so many overtones and undertones, that they had the effect of a piano player striking chords rapidly but somehow articulating separately each note in the chord, and its vibrating subtones." Or, as Coltrane himself said, "I start in the middle of a sentence and move both directions at once." The cascade of notes during his powerful solos showed his infatuation with chord progressions, culminating in the virtuoso performance of "Giant Steps" (1959). Coltrane's tone on the tenor sax was huge and dark, with clear definition and full body, even in the highest and lowest registers. His vigorous, intense style was original, but traces of his idols Johnny Hodges and Lester Young can be discerned in his legato phrasing and portamento (or, in jazz vernacular, "smearing," in which the instrument glides from note to note with no discernible breaks). From Monk he learned the technique of multiphonics, by which a reed player can produce multiple tones simultaneously by using a relaxed embouchure (i.e., position of the lips, tongue, and teeth), varied pressure, and special fingerings. In the late 1950s, Coltrane used multiphonics for simple harmony effects (as on his 1959 recording of "Harmonique"); in the 1960s, he employed the technique more frequently, in passionate, screeching musical passages. Coltrane returned to Davis's group in 1958, contributing to the "modal phase" albums Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), both considered essential examples of 1950s modern jazz. (Davis at this point was experimenting with modes-i.e., scale patterns other than major and minor.) His work on these recordings was always proficient and often brilliant, though relatively subdued and cautious. After ending his association with Davis in 1960, Coltrane formed his own acclaimed quartet, featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. At this time Coltrane began playing soprano saxophone in addition to tenor. Throughout the early 1960s Coltrane focused on mode-based improvisation in which solos were played atop one- or two-note accompanying figures that were repeated for extended periods of time (typified in his recordings of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things"). At the same time, his study of the musics of India and Africa affected his approach to the soprano sax. These influences, combined with a unique interplay with the drums and the steady vamping of the piano and bass, made the Coltrane quartet one of the most noteworthy jazz groups of the 1960s. Coltrane's wife, Alice (also a jazz musician and composer), played the piano in his band during the last years of his life. During the short period between 1965 and his death in 1967, Coltrane's work expanded into a free, collective (simultaneous) improvisation based on prearranged scales. It was the most radical period of his career, and his avant-garde experiments divided critics and audiences. Coltrane's best-known work spanned a period of only 12 years (1955-67), but, because he recorded prolifically, his musical development is well-documented. His somewhat tentative, relatively melodic early style can be heard on the Davis-led albums recorded for the Prestige and Columbia labels during 1955 and '56. Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane (1957) reveals Coltrane's growth in terms of technique and harmonic sense, an evolution further chronicled on Davis's albums Milestones and Kind of Blue. Most of Coltrane's early solo albums are of a high quality, particularly Blue Train (1957), perhaps the best recorded example of his early hard bop style (see bebop). Recordings from the end of the decade, such as Giant Steps (1959) and My Favorite Things (1960), offer dramatic evidence of his developing virtuosity. Nearly all of the many albums Coltrane recorded during the early 1960s rank as classics; A Love Supreme (1964), a deeply personal album reflecting his religious commitment, is regarded as especially fine work. His final forays into avant-garde and free jazz are represented by Ascension and Meditations (both 1965), as well as several albums released posthumously." ^ Hide Bio for John Coltrane • Show Bio for Wynton Kelly "Wynton Kelly (pianist) was born in Jamaica on December 2, 1931 and passed away on April 12, 1971 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Wynton Kelly was a greatly underrated talent, who was both an elegant piano soloist with a rhythmically infectious solo style in which he combined boppish lines with a great feeling for the blues as well as a particularly accomplished accompanist, gifted with perfect pitch and a highly individual block chording style. Kelly's work was always highly melodic, especially in his ballad performances, while an irresistible sense of swing informed his mid and up-tempo performances. Though he was born on the island of Jamaica, Wynton grew up in Brooklyn. His academic training appears to have been brief, but he was a fast musical developer who made his professional debut in 1943, at the age of eleven or twelve. His initial musical environment was the burgeoning Rhythm and Blues scene of the mid to late 1940s. Wynton played his first important gig with the R&B combo of tenor saxophonist Ray Abrams in 1947. He spent time in hard hitting R&B combos led by Hot Lips Page, Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, in addition to the gentler environment of Johnny Moore's Three Blazers. In April 1949, Wynton played piano backing vocalist Babs Gonzales in a band that also included J.J. Johnson, Roy Haynes and a young Sonny Rollins. Kelly's first big break in the jazz world came in 1951, when he became Dinah Washington's accompanist. In July 1951 Kelly also made his recording debut as a leader on the Blue Note label at the age of 19. After his initial stint with Dinah Washington Kelly gigged with the combos of Lester Young and Dizzy Gillespie and recorded with Gillespie's quintet in 1952. Wynton fulfilled his army service between 1952 and the summer or 1954 and then rejoined Washington and the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band (1957). By this time Kelly had become one of the most in demand pianists on record. He distinguished himself on record with such talent as J.J. Johnson, Sonny Rollins, Johnny Griffin and especially Hank Mobley whom Kelly inspired to some of his best work on classic Blue Note albums like Soul Station, Work Out, and Roll Call. Wynton proved himself as a superb accompanist on the Billie Holiday Clef sessions of June 1956 and showed his mettle both as an accompanist and soloist on the star-studded Norman Granz session with Coleman Hawkins, Paul Gonsalves, Dizzy Gillespie and Stan Getz in 1957 that produced the fine Sittin' In album on the Verve label. In 1957 Kelly left Gillespie and formed his own trio. He finally recorded his second album as a leader for the Riverside label in January 1958, six years after his Blue Note debut. In early 1959 Miles Davis invited Wynton to joint his sextet as a replacement for Bill Evans. Kind of Blue, recorded in March 1959, on which he shares the piano stool with Evans, Kelly excels on the track "Freddie Freeloader" a medium temp side that is closest to the more theory-free jazz of the mid-fifties. Wynton proved a worthy successor to Red Garland and Bill Evans in the Miles Davis combo, together with bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb, an old colleague from Dinah Washington's rhythm section, he established a formidable rapport. Kelly likewise appears on a single track from John Coltrane's Giant Steps, replacing Tommy Flanagan on "Naima". During his stay with Davis, Kelly recorded his fine Kelly Blue for Riverside and three albums for Vee Jay. By the end of 1962 Kelly, Chambers and Cobb formed the Wynton Kelly Trio, which soon made its mark. The Kelly Trio remained a regular unit for a number of years and reached the height of their popularity after they joined up with guitarist Wes Montgomery, resulting in three albums, a live set in New York's Half Note, a September 1965 studio album for Verve, and a live set at the Half Note for the Xanadu Label. Kelly's trio, now with Cecil McBee and Ron McClure kept working during till the late 1960s. Kelly suffered from epilepsy most of his life, and succumbed to a heart attack induced by a seizure in Toronto, Canada on April 12, 1971 at the age of 39. Kelly had a daughter, Tracy, in 1963, with partner Anne. The track "Little Tracy", on the LP Comin' in the Back Door, is named after Kelly's daughter. Tracy Matisak is a now a Philadelphia television personality. Kelly recorded as a leader for Blue Note, Riverside Records, Vee-Jay, Verve, and Milestone. Kelly had a daughter, Tracy, in 1963, with partner Anne. The track "Little Tracy", on the LP Comin' in the Back Door, is named after Kelly's daughter. Tracy Matisak is a now a Philadelphia television personality. Kelly's second cousin, bassist Marcus Miller, also performed with Miles Davis in the 1980s and 1990s. Another cousin is pianist Randy Weston." ^ Hide Bio for Wynton Kelly • Show Bio for Paul Chambers "Paul Laurence Dunbar Chambers Jr. (April 22, 1935 - January 4, 1969) was an American jazz double bassist. A fixture of rhythm sections during the 1950s and 1960s, his importance in the development of jazz bass can be measured not only by the extent of his work in this short period, but also by his impeccable timekeeping and virtuosic improvisations. He was also known for his bowed solos. Chambers recorded about a dozen albums as a leader or co-leader, and over 100 more as a sideman, especially as the anchor of trumpeter Miles Davis's "first great quintet" (1955-63) and with pianist Wynton Kelly (1963-68). Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on April 22, 1935, to Paul Lawrence Chambers and Margaret Echos. He was brought up in Detroit, Michigan following the death of his mother. He began playing music with several of his schoolmates on the baritone horn. Later he took up the tuba. "I got along pretty well, but it's quite a job to carry it around in those long parades, and I didn't like the instrument that much". " ^ Hide Bio for Paul Chambers • Show Bio for Jimmy Cobb "Wilbur James Cobb (January 20, 1929 - May 24, 2020) was an American jazz drummer. He was part of Miles Davis's First Great Sextet. At the time of his death, he had been the band's last surviving member for nearly thirty years. He was awarded an NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship in 2009. Cobb was born in Washington, D.C. on January 20, 1929. Before he began his music career, he listened to jazz albums and stayed awake into the late hours of the night in order to listen to Symphony Sid broadcasting from New York City. Raised Catholic, he was also exposed to Church music. Cobb started his touring career in 1950 with the saxophonist Earl Bostic. He subsequently performed with vocalist Dinah Washington, pianist Wynton Kelly, saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, bassist Keter Betts, Frank Wess, Leo Parker, and Charlie Rouse. His website also recounts his gigs with Billie Holiday, Pearl Bailey, and Dizzy Gillespie that took place before 1957. Cobb joined Miles Davis in 1958 as part of the latter's First Great Sextet, after Adderley recommended him to Davis. Cobb's best known recorded work is on Davis' Kind of Blue (1959). Cobb was the last surviving player from the sessions, a distinction that, after Davis's death in 1991, he held for almost three decades. He also played on other Davis albums, including Sketches of Spain (1960), Someday My Prince Will Come (1961), Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall (1962), In Person Friday and Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, Complete, and briefly on Porgy and Bess (1959) and Sorcerer. His subtle and understated demeanor drew the admiration of many including Davis. However, this also meant that he did not get the same level of recognition that his fellow drummers would. Cobb had the propensity to eschew publicity and did not record his first set as bandleader until 1983, with the release of So Nobody Else Can Hear. Cobb left the band in 1963, when Tony Williams was brought in by Davis. He formed a trio with pianist Wynton Kelly and bassist Paul Chambers, both of whom were part of Davis' rhythm section. The group recorded with Kenny Burrell (guitar) and J. J. Johnson (trombone), before breaking up at the end of the decade. Cobb went on to join the Great Jazz Trio, together with Hank Jones on piano and Eddie Gómez on bass. He also toured with Sarah Vaughan during the 1970s, and taught at Stanford University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and Berklee College of Music. He played in a tribute band called "4 Generations of Miles", together with Ron Carter (bass), Mike Stern (guitar), and George Coleman (tenor saxophone). During his career, Cobb worked with Bill Evans, Clark Terry, Stan Getz, John Coltrane, Wes Montgomery, Art Pepper, Wayne Shorter, Benny Golson, Gil Evans, Kenny Dorham, Frank Strozier, Bobby Timmons, Booker Little, Johnny Griffin, Akiko Tsuruga, Bertha Hope, Hamiet Bluiett, Nat Adderley, Mark Murphy, Jon Hendricks, Joe Henderson, Fathead Newman, Geri Allen, Larry Willis, Walter Booker, Red Garland, Richie Cole, Ernie Royal, Jerome Richardson, Jimmy Cleveland, Philly Joe Jones, Sonny Stitt, Nancy Wilson, Ricky Ford, Richard Wyands, John Webber, and Peter Bernstein, among many others." ^ Hide Bio for Jimmy Cobb

4/10/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

4/10/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

4/10/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

4/10/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

4/10/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. So What 13:26

2. On Green Dolphin Street 14:40

3. Walkin' 15:55

4. All Blues 16:17

5. So What 15:06

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Free Improvisation

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Quintet Recordings

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

New in Improvised Music

Recent Releases and Best Sellers

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.